Volume 10, Issue 4 (December 2025)

J Environ Health Sustain Dev 2025, 10(4): 2843-2858 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.IUMS.REC.1402.027

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kowsari M H, Yeganeh M, Ansari M, Abdolahi Nejad B, Hasham Firooz M, Farzadkia M. Comparative Efficiency of Mesophilic Anaerobic Digestion and Aerated Static Pile Composting in the Stabilization of Municipal Wastewater Sludge. J Environ Health Sustain Dev 2025; 10 (4) :2843-2858

URL: http://jehsd.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1062-en.html

URL: http://jehsd.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1062-en.html

Mohammad Hasan Kowsari

, Mojtaba Yeganeh

, Mojtaba Yeganeh

, Mohsen Ansari

, Mohsen Ansari

, Behnaz Abdolahi Nejad

, Behnaz Abdolahi Nejad

, Masoumeh Hasham Firooz

, Masoumeh Hasham Firooz

, Mahdi Farzadkia *

, Mahdi Farzadkia *

, Mojtaba Yeganeh

, Mojtaba Yeganeh

, Mohsen Ansari

, Mohsen Ansari

, Behnaz Abdolahi Nejad

, Behnaz Abdolahi Nejad

, Masoumeh Hasham Firooz

, Masoumeh Hasham Firooz

, Mahdi Farzadkia *

, Mahdi Farzadkia *

Research Center for Environmental Health Technology, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran & Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 808 kb]

(35 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (98 Views)

.JPG)

Figure 1: Tehran South Wastewater Treatment Plant facilities.

.JPG)

Figure 2: Laboratory-scale anaerobic digestion reactor.

.JPG)

Figure 3: Loading stages of the aerated static pile composting reactor.

.JPG)

Figure 4: Schematic of the aerated static pile sludge composting reactor during the thermophilic phase.

Results

Characterization of Raw Sludge from the South Tehran WWTP

The physicochemical properties of the primary and secondary sludges used in this study are presented in Table 2. The pH values were near neutral for both sludges. Secondary sludge exhibited a significantly higher total solids (TS) content (7.2 ± 0.4%) than primary sludge (2.5 ± 0.2%), indicating a greater concentration through the activated sludge process. The volatile solids-to-total solids (VS/TS) ratios were 83.78 ± 1.2% and 76.34 ± 1.5% for secondary and primary sludge, respectively, confirming their high organic content. Secondary sludge also showed higher concentrations of total volatile fatty acids (TVFA: 1220 ± 45 mg/L) and alkalinity (670 ± 25 mg/L as CaCO₃) than primary sludge (TVFA: 870 ± 35 mg/L; alkalinity: 469 ± 20 mg/L), reflecting its more advanced biological activity and buffering capacity.

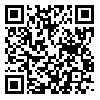

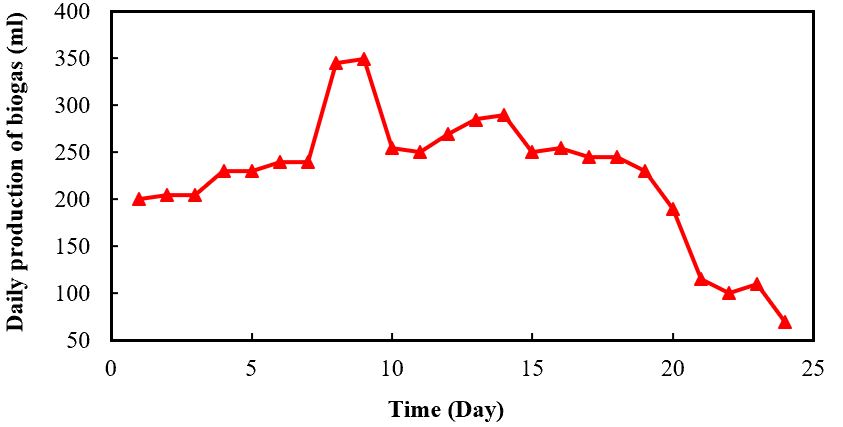

Figure 5: Daily biogas production during anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludg.

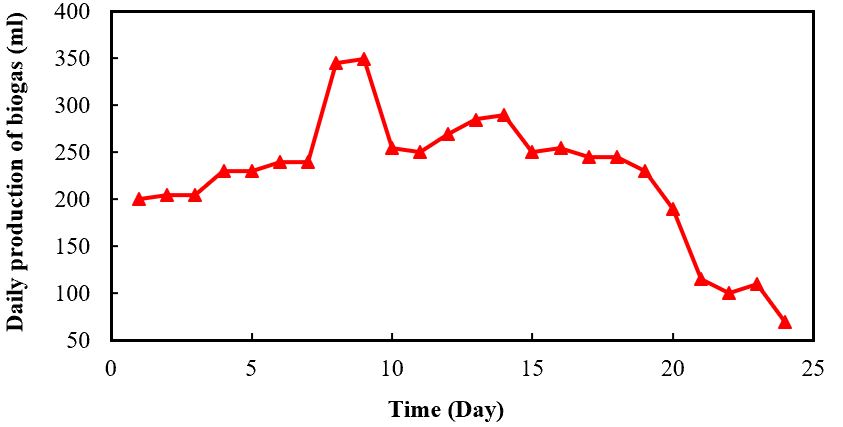

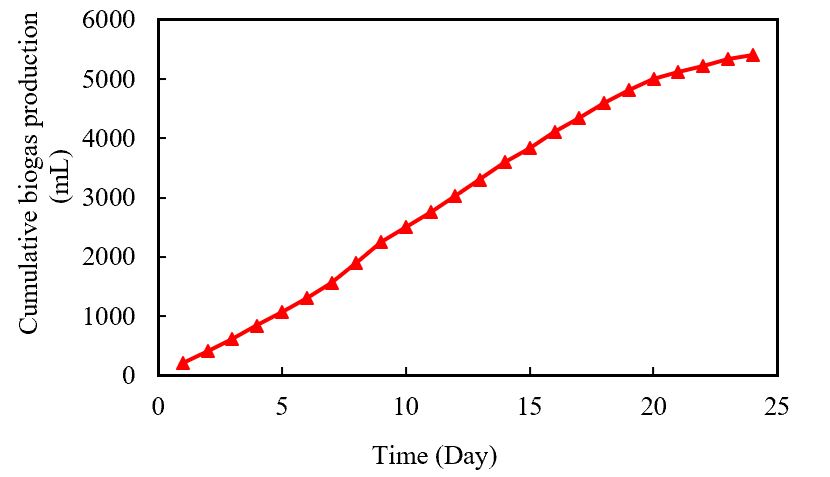

Figure 6: Cumulative biogas production during anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludge.

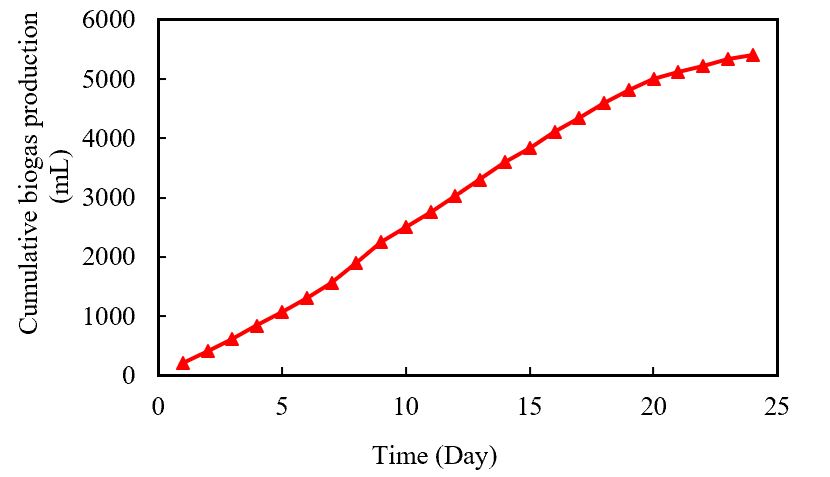

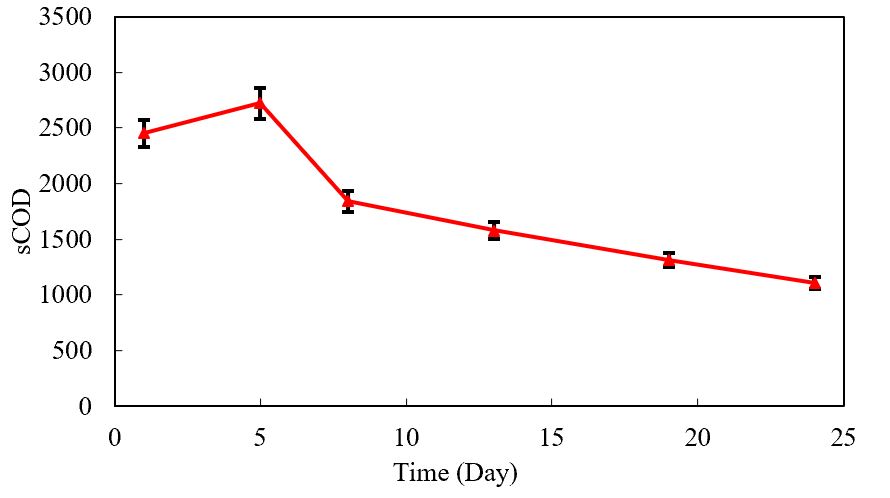

Figure 7: Temporal variations in soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD) during anaerobic digestion.

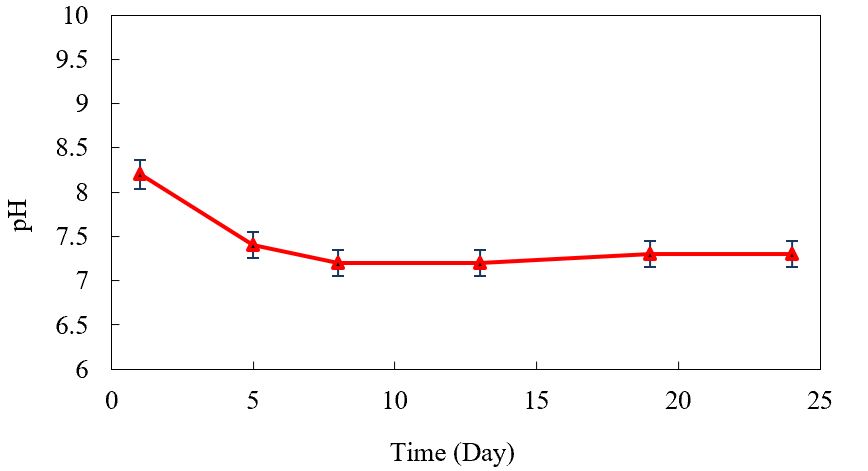

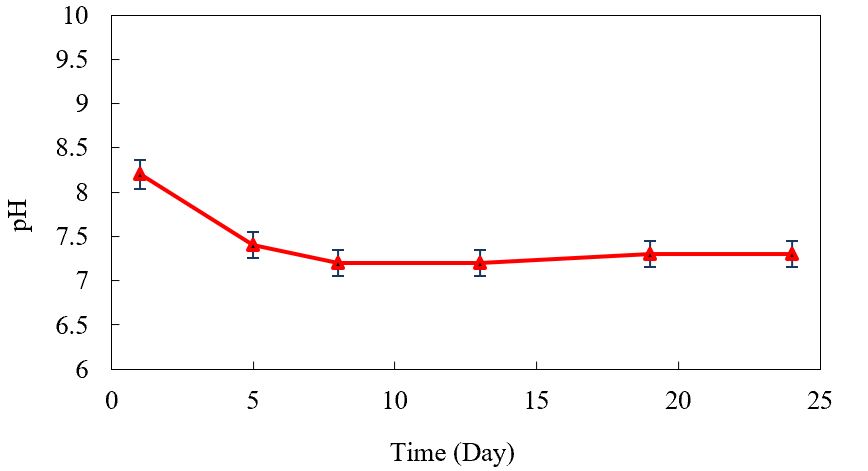

Figure 8: pH variations during the anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludge.

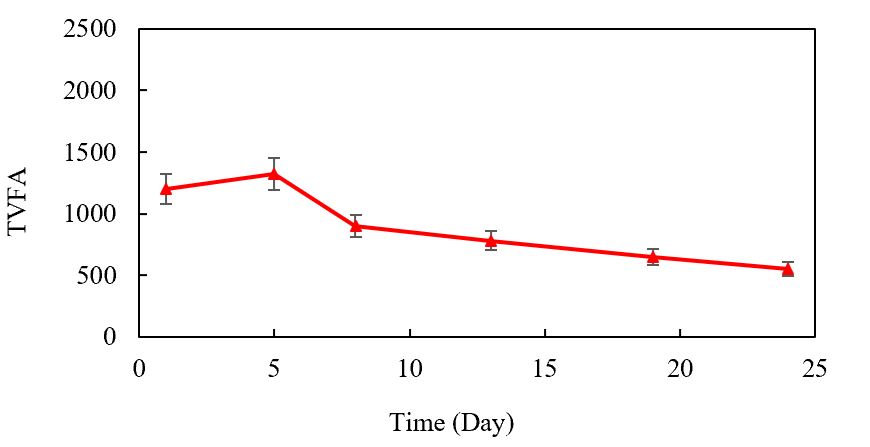

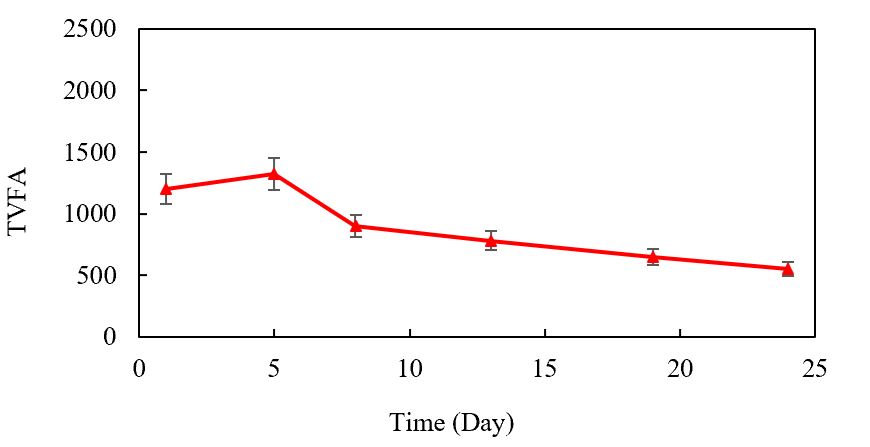

Figure 9: Temporal variations in total volatile fatty acids (TVFA) during anaerobic digestion.

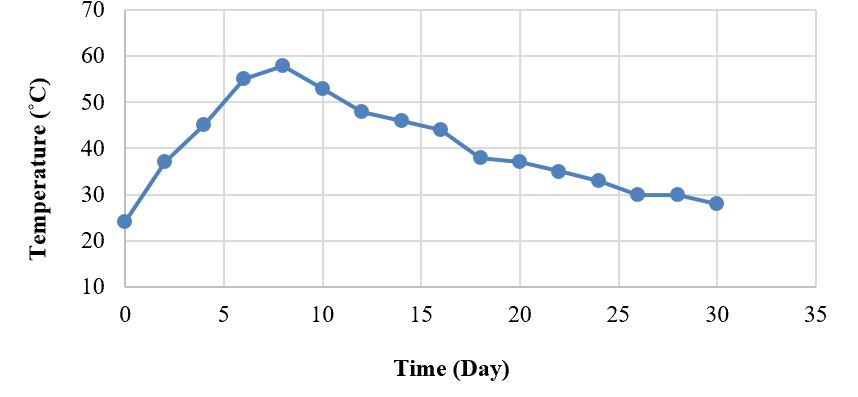

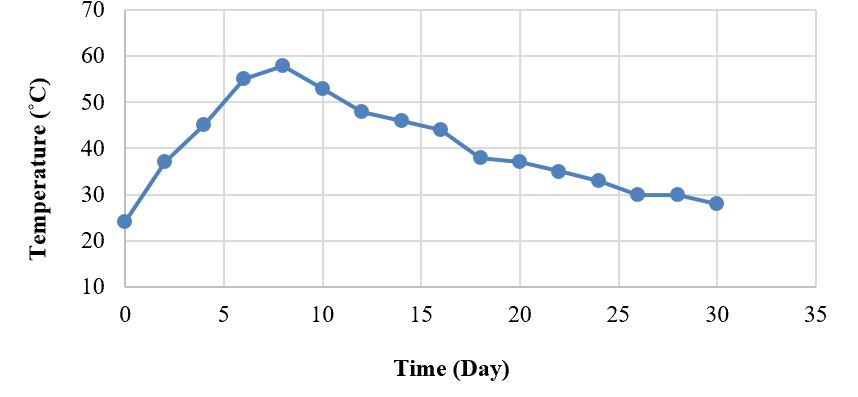

Figure 10: Temperature profile during the rapid phase of sludge composting in a statically aerated pile reactor.

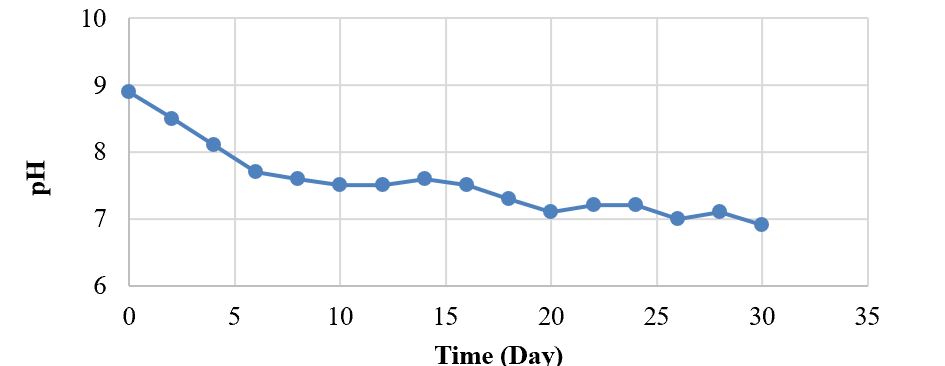

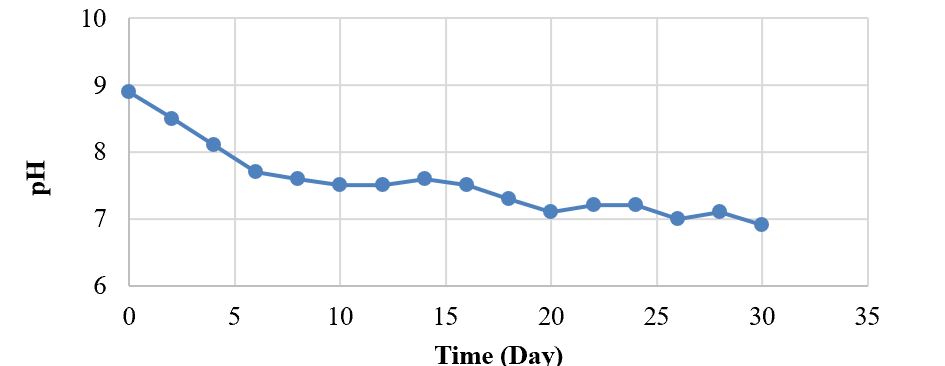

Figure 11: pH variations during the rapid phase of sludge composting in a statically aerated pile reactor.

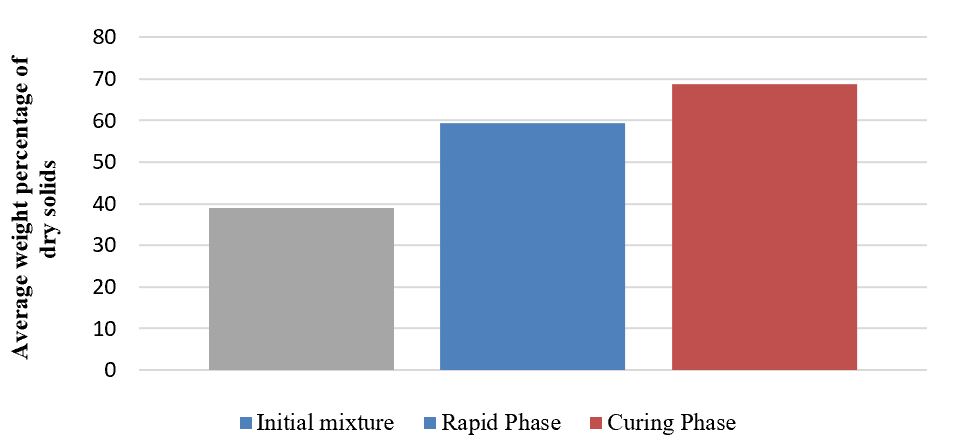

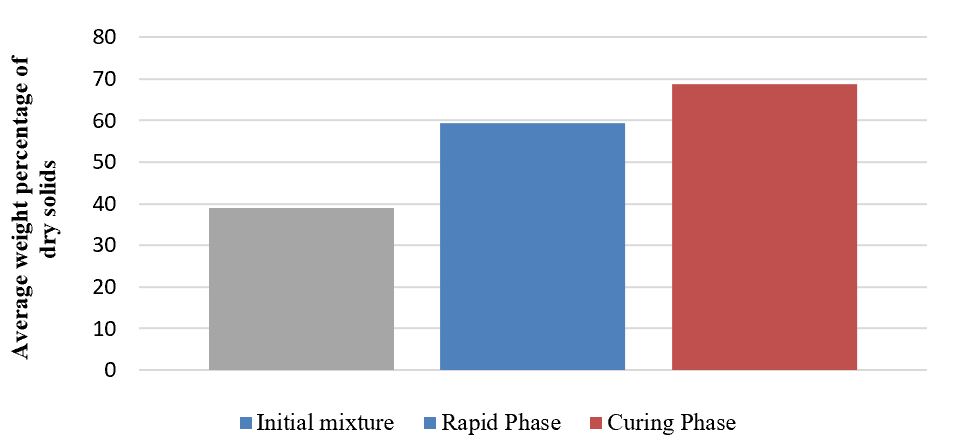

Figure 12: Average weight percentage of dry solids.

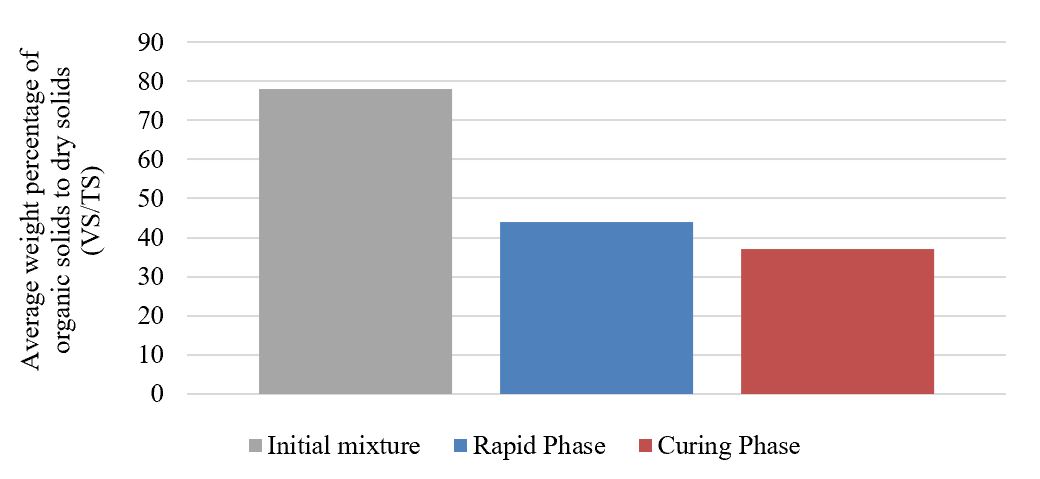

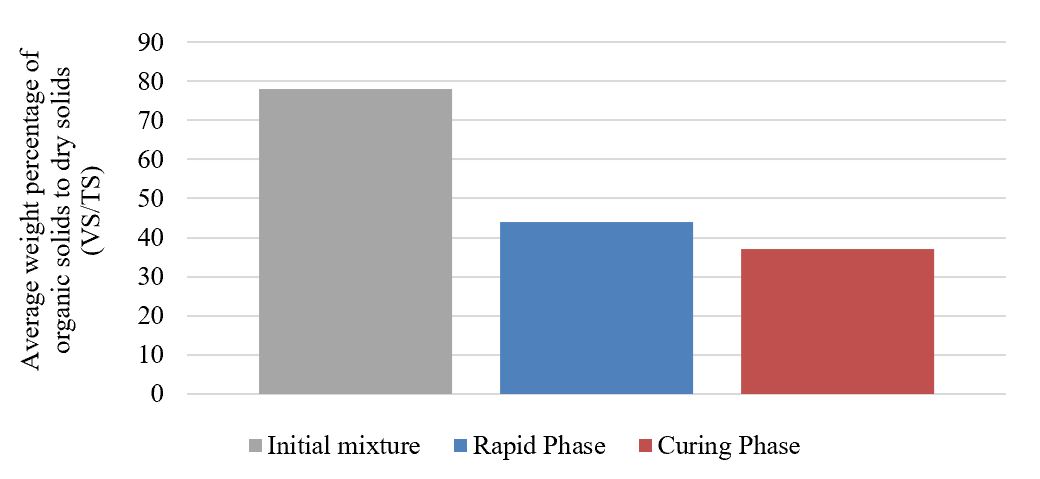

Figure 13: Average weight percentage of organic solids to dry solids (VS/TS).

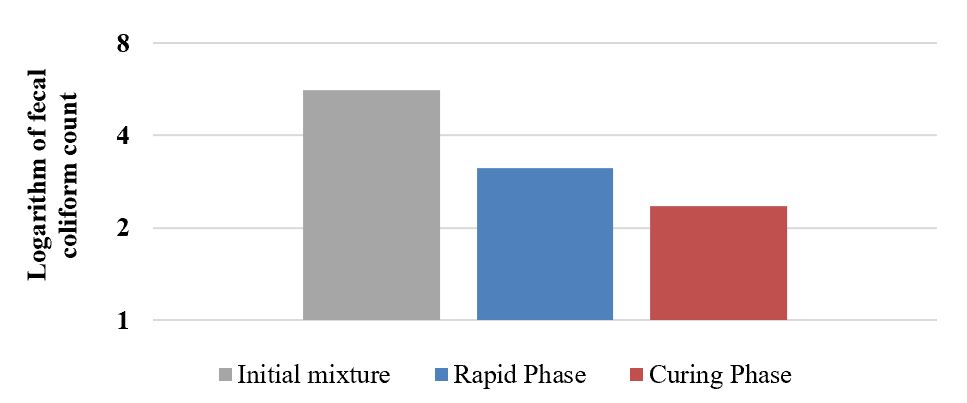

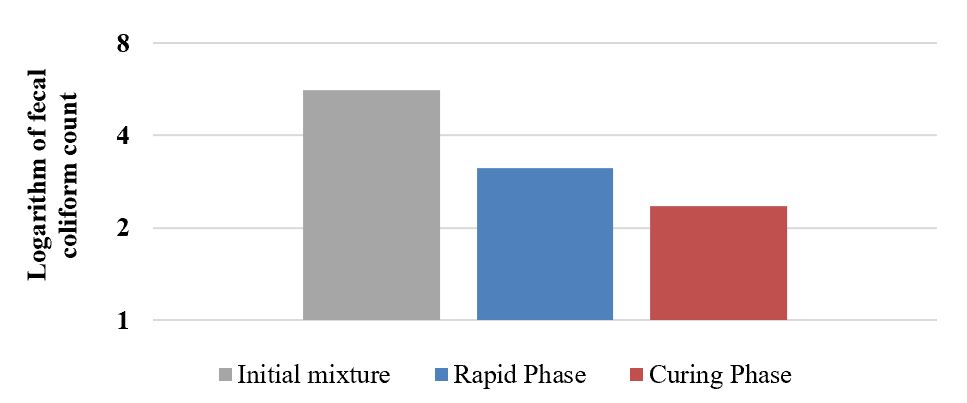

Figure 14: Reduction in fecal coliform counts during different stages of sludge composting.

Full-Text: (7 Views)

Comparative Efficiency of Mesophilic Anaerobic Digestion and Aerated Static Pile Composting in the Stabilization of Municipal Wastewater Sludge

Mohammad Hasan Kowsari 1,2,3, Mojtaba Yeganeh 1,2, Mohsen Ansari 4, Behnaz Abdolahi Nejad 1,

Masoumeh Hasham Firooz 5, Mahdi Farzadkia 1,2*

1 Research Center for Environmental Health Technology, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2 Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3 Student Research Committee, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4 Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran.

5 Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Mohammad Hasan Kowsari 1,2,3, Mojtaba Yeganeh 1,2, Mohsen Ansari 4, Behnaz Abdolahi Nejad 1,

Masoumeh Hasham Firooz 5, Mahdi Farzadkia 1,2*

1 Research Center for Environmental Health Technology, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2 Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3 Student Research Committee, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4 Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran.

5 Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

| A R T I C L E I N F O | ABSTRACT | |

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE | Introduction: Stabilization of municipal wastewater sludge is a critical requirement for mitigating environmental and public health risks. This study provides a comparative evaluation of mesophilic anaerobic digestion (AD) and aerated static pile (ASP) composting for sludge stabilization at Iran’s largest municipal wastewater treatment plant, with a focus on process efficiency, hygienic quality, and end-product usability. Materials and Methods: Laboratory-scale experiments were conducted using batch mesophilic anaerobic digestion (35 °C, 24 days) and aerated static pile composting. The composting process employed sludge conditioned with bulking and amendment agents under controlled aeration, including a 6-day thermophilic phase within a 30-day operational period. Process performance was assessed based on volatile solids reduction, pathogen inactivation, and biogas production. Results: ASP composting demonstrated superior stabilization and hygienization performance, achieving more than 50% volatile solids reduction and over 3-log fecal coliform reduction, resulting in compost meeting USEPA Class A standards. In contrast, anaerobic digestion achieved approximately 40% volatile solids reduction and produced 5405 mL of biogas, yielding biosolids classified as USEPA Class B. Conclusion: While mesophilic anaerobic digestion offers the advantage of renewable energy recovery, aerated static pile composting provides a more hygienically robust pathway for producing stabilized, high-quality compost suitable for agricultural applications. The findings highlight that the selection of sludge treatment technology should be context-driven, balancing priorities between energy generation and the production of sanitized, agriculturally valuable biosolids. |

|

Article History: Received: 08 October 2025 Accepted: 20 November 2025 |

||

*Corresponding Author: Mahdi Farzadkia Email: mahdifarzadkia@gmail.com Tel: +98 9122588677 |

||

Keywords: Wastewater, Sewage Sludge, Anaerobic Digestion, Composting, Aeration, Biogas. |

Citation: Kowsari MH, Yeganeh M, Ansari M, et al. Comparative Efficiency of Mesophilic Anaerobic Digestion and Aerated Static Pile Composting in the Stabilization of Municipal Wastewater Sludge. J Environ Health Sustain Dev. 2025; 10(4): 2843-58.

Introduction

The management of municipal wastewater sludge represents one of the most critical technical and economic challenges in achieving sustainable wastewater treatment. Inadequate disposal or stabilization practices can lead to the uncontrolled release of heavy metals, emerging micropollutants, and pathogenic microorganisms, posing significant risks to public health and the integrity of natural ecosystems 1, 2. Accordingly, the development and implementation of effective sludge stabilization strategies remain a top priority for environmental engineers and public health authorities 3.

In Iran, the rapid expansion of municipal wastewater treatment facilities in recent decades has resulted in the continuous production of large volumes of sludge. However, limited regulatory oversight and insufficient quality monitoring have led to the widespread direct discharge of untreated sludge into the environment. Recent investigations indicate that nearly 80% of the sludge generated by municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) nationwide remains inadequately stabilized 4, posing serious risks to public health and environmental sustainability 5. Although there is no accurate information or statistics on the quantity of sludge produced in the country's wastewater treatment plants, the amount of sludge produced at the wastewater treatment plant in southern Tehran has been reported to be 1,125 tons per month 6.

The high organic content and nutrient load of sewage sludge render it a potentially valuable resource for bioenergy generation, particularly biogas production, and for the creation of beneficial by-products such as compost 7. Its substantial concentrations of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients support its application as a soil amendment to enhance fertility and restore degraded soils. Nevertheless, the direct use of untreated sludge is associated with severe environmental and health hazards due to toxic heavy metals, including lead ( > 100 mg/kg) and cadmium ( > 20 mg/kg), which threaten soil quality, crop safety, and food chain security (EPA, 2020; WHO, 2006). Consequently, adequate sludge treatment and stabilization are universally recognized as essential prerequisites for environmental discharge or reuse.

Despite its importance, sludge management imposes complex technical and financial challenges. Processes such as collection, thickening, dewatering, and disposal can account for up to 50% of WWTP operational expenditure 8. Hence, identifying cost-effective and reliable stabilization technologies remains a major challenge. Among the available options, anaerobic digestion (AD) and aerated static pile (ASP) composting have emerged as two of the most widely implemented methods for sludge stabilization globally 9.

Anaerobic digestion, with a documented operational history extending back to the mid-nineteenth century, has evolved into a cornerstone technology for sludge management 10. Its ability to reduce pathogen levels, mineralize organic matter, and generate renewable biogas has established AD as a preferred practice in many European and North American WWTPs 11, 12. However, the high investment and operating costs of anaerobic sludge digestion facilities, as well as the need to meet Class B conditions of USEPA standards for sludge produced under mesophilic operating conditions, are known to be among the limitations of these reactors 13, 14.

Sludge composting was one of the methods proposed and used in response to these limitations in the early 20th century 15, 16. This biological process oxidizes organic matter, producing a stabilized, nutrient-rich product with proven agronomic values. In addition to reducing sludge volume and pathogen content, composting enhances soil structure, water retention, and microbial activity 17-19.

Traditionally, composting has been employed to improve the quality of biosolids produced by WWTPs, facilitating their reuse as fertilizers or soil conditioners 20. However, direct composting of raw sludge presents technical challenges owing to its high moisture content (often > 90%) and excessive organic loading 21. To address these constraints, several optimization approaches have been explored including the use of bulking agents, chemical coagulants, and adjustment of the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio each enhancing the suitability of sludge for composting 22, 23.

Anaerobic digestion remains the dominant sludge stabilization method worldwide, including in Iran. However, recent studies suggest that its operational efficiency often falls short of expectations. Against this background, the present study conducted a comparative evaluation of anaerobic digestion and aerobic composting for sludge stabilization, focusing on the sludge generated at the South Tehran WWTP, the largest facility of its kind in the country.

The plant serves a population of approximately 3.15 million, with a design capacity of 4.2 million upon the full completion of its eight operational modules. Operating on a conventional activated sludge process, the STWWTP treats an average daily flow of approximately 675,000 m³, with the treated effluent primarily reused for agricultural irrigation in the Varamin and Rey plains. Within the sludge management line, primary sludge undergoes gravitational thickening, whereas waste-activated sludge is mechanically thickened. These two streams are then homogenized and fed into mesophilic anaerobic digesters (operating at 35–37°C). The biogas produced is utilized in an on-site cogeneration plant, recognized as one of the world's largest biogas-based sludge-to-energy facilities, generating approximately 60 GWh of electricity and 200 TJ of thermal energy annually. Following anaerobic digestion, the sludge is dewatered and dried, yielding over 300 tons per day of biosolids that are primarily used for agricultural and land-rehabilitation purposes. This facility, with its integrated energy recovery system, provides a highly relevant large-scale context for comparing the established anaerobic digestion process with the alternative aerated static pile composting method for sludge stabilization. Figure 1 provides an overview of WWTP infrastructure.

The management of municipal wastewater sludge represents one of the most critical technical and economic challenges in achieving sustainable wastewater treatment. Inadequate disposal or stabilization practices can lead to the uncontrolled release of heavy metals, emerging micropollutants, and pathogenic microorganisms, posing significant risks to public health and the integrity of natural ecosystems 1, 2. Accordingly, the development and implementation of effective sludge stabilization strategies remain a top priority for environmental engineers and public health authorities 3.

In Iran, the rapid expansion of municipal wastewater treatment facilities in recent decades has resulted in the continuous production of large volumes of sludge. However, limited regulatory oversight and insufficient quality monitoring have led to the widespread direct discharge of untreated sludge into the environment. Recent investigations indicate that nearly 80% of the sludge generated by municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) nationwide remains inadequately stabilized 4, posing serious risks to public health and environmental sustainability 5. Although there is no accurate information or statistics on the quantity of sludge produced in the country's wastewater treatment plants, the amount of sludge produced at the wastewater treatment plant in southern Tehran has been reported to be 1,125 tons per month 6.

The high organic content and nutrient load of sewage sludge render it a potentially valuable resource for bioenergy generation, particularly biogas production, and for the creation of beneficial by-products such as compost 7. Its substantial concentrations of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients support its application as a soil amendment to enhance fertility and restore degraded soils. Nevertheless, the direct use of untreated sludge is associated with severe environmental and health hazards due to toxic heavy metals, including lead ( > 100 mg/kg) and cadmium ( > 20 mg/kg), which threaten soil quality, crop safety, and food chain security (EPA, 2020; WHO, 2006). Consequently, adequate sludge treatment and stabilization are universally recognized as essential prerequisites for environmental discharge or reuse.

Despite its importance, sludge management imposes complex technical and financial challenges. Processes such as collection, thickening, dewatering, and disposal can account for up to 50% of WWTP operational expenditure 8. Hence, identifying cost-effective and reliable stabilization technologies remains a major challenge. Among the available options, anaerobic digestion (AD) and aerated static pile (ASP) composting have emerged as two of the most widely implemented methods for sludge stabilization globally 9.

Anaerobic digestion, with a documented operational history extending back to the mid-nineteenth century, has evolved into a cornerstone technology for sludge management 10. Its ability to reduce pathogen levels, mineralize organic matter, and generate renewable biogas has established AD as a preferred practice in many European and North American WWTPs 11, 12. However, the high investment and operating costs of anaerobic sludge digestion facilities, as well as the need to meet Class B conditions of USEPA standards for sludge produced under mesophilic operating conditions, are known to be among the limitations of these reactors 13, 14.

Sludge composting was one of the methods proposed and used in response to these limitations in the early 20th century 15, 16. This biological process oxidizes organic matter, producing a stabilized, nutrient-rich product with proven agronomic values. In addition to reducing sludge volume and pathogen content, composting enhances soil structure, water retention, and microbial activity 17-19.

Traditionally, composting has been employed to improve the quality of biosolids produced by WWTPs, facilitating their reuse as fertilizers or soil conditioners 20. However, direct composting of raw sludge presents technical challenges owing to its high moisture content (often > 90%) and excessive organic loading 21. To address these constraints, several optimization approaches have been explored including the use of bulking agents, chemical coagulants, and adjustment of the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio each enhancing the suitability of sludge for composting 22, 23.

Anaerobic digestion remains the dominant sludge stabilization method worldwide, including in Iran. However, recent studies suggest that its operational efficiency often falls short of expectations. Against this background, the present study conducted a comparative evaluation of anaerobic digestion and aerobic composting for sludge stabilization, focusing on the sludge generated at the South Tehran WWTP, the largest facility of its kind in the country.

The plant serves a population of approximately 3.15 million, with a design capacity of 4.2 million upon the full completion of its eight operational modules. Operating on a conventional activated sludge process, the STWWTP treats an average daily flow of approximately 675,000 m³, with the treated effluent primarily reused for agricultural irrigation in the Varamin and Rey plains. Within the sludge management line, primary sludge undergoes gravitational thickening, whereas waste-activated sludge is mechanically thickened. These two streams are then homogenized and fed into mesophilic anaerobic digesters (operating at 35–37°C). The biogas produced is utilized in an on-site cogeneration plant, recognized as one of the world's largest biogas-based sludge-to-energy facilities, generating approximately 60 GWh of electricity and 200 TJ of thermal energy annually. Following anaerobic digestion, the sludge is dewatered and dried, yielding over 300 tons per day of biosolids that are primarily used for agricultural and land-rehabilitation purposes. This facility, with its integrated energy recovery system, provides a highly relevant large-scale context for comparing the established anaerobic digestion process with the alternative aerated static pile composting method for sludge stabilization. Figure 1 provides an overview of WWTP infrastructure.

.JPG)

Figure 1: Tehran South Wastewater Treatment Plant facilities.

While AD dominates current practice, composting represents a compelling, yet under-evaluated, alternative, especially for producing a high-quality, safe soil conditioner, which may be as important as energy recovery. Therefore, this study aimed to provide a novel comparative evaluation of mesophilic AD and ASP composting for stabilizing sludge from STWWTP. The core objective was to assess and compare the efficiency of organic matter stabilization, pathogen inactivation, and process operability between the two technologies through parallel laboratory-scale simulations.

By integrating rigorous physicochemical and microbiological analyses, this study seeks to generate evidence-based insights that can inform sustainable and context-specific sludge management strategies in Iran and similar settings.

Materials and Methods

Sludge Sampling and Characterization

The sludge feedstock for both anaerobic digestion (AD) and composting experiments was derived from the main sludge stream of the Tehran South WWTP. In the plant process line, primary sludge (after gravitational thickening) and secondary waste activated sludge (after chemical conditioning and dewatering) are combined in a homogenization tank before being fed to the mesophilic anaerobic digesters. Representative sludge samples were collected from the homogenized mixture prior to its entry into the digesters. Samples were immediately transferred to plastic containers, preserved at 4 °C, and transported to the laboratory within two hours of collection. The physicochemical properties, including pH, soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD), total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), and total volatile fatty acids (TVFA), were analyzed in triplicate according to the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater 24, with results expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Anaerobic Sludge Digestion Reactor

Anaerobic digestion was simulated using 500-mL glass serum reactors equipped with gas outlets. Each reactor contained a mixture of primary and secondary sludge inoculated with digested sludge at 10% (v/v). The reactors were operated in batch mode under mesophilic conditions (35 °C) for 24 days. Table 1 summarizes the loading condition. The temperature and agitation were controlled using a thermostatic water bath with a magnetic stirrer. The daily biogas production was measured using water displacement in a graduated cylinder. Figure 2 shows the experimental setup used in this study.

By integrating rigorous physicochemical and microbiological analyses, this study seeks to generate evidence-based insights that can inform sustainable and context-specific sludge management strategies in Iran and similar settings.

Materials and Methods

Sludge Sampling and Characterization

The sludge feedstock for both anaerobic digestion (AD) and composting experiments was derived from the main sludge stream of the Tehran South WWTP. In the plant process line, primary sludge (after gravitational thickening) and secondary waste activated sludge (after chemical conditioning and dewatering) are combined in a homogenization tank before being fed to the mesophilic anaerobic digesters. Representative sludge samples were collected from the homogenized mixture prior to its entry into the digesters. Samples were immediately transferred to plastic containers, preserved at 4 °C, and transported to the laboratory within two hours of collection. The physicochemical properties, including pH, soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD), total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), and total volatile fatty acids (TVFA), were analyzed in triplicate according to the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater 24, with results expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Anaerobic Sludge Digestion Reactor

Anaerobic digestion was simulated using 500-mL glass serum reactors equipped with gas outlets. Each reactor contained a mixture of primary and secondary sludge inoculated with digested sludge at 10% (v/v). The reactors were operated in batch mode under mesophilic conditions (35 °C) for 24 days. Table 1 summarizes the loading condition. The temperature and agitation were controlled using a thermostatic water bath with a magnetic stirrer. The daily biogas production was measured using water displacement in a graduated cylinder. Figure 2 shows the experimental setup used in this study.

Table 1: Organic loading conditions in the anaerobic sludge digesters

| Components | Volume (mL) |

| Mixture of primary and secondary sludge | 360 |

| Anaerobic digested sludge (inoculum) | 40 |

| Working volume | 400 |

| Total reactor volume | 500 |

.JPG)

Figure 2: Laboratory-scale anaerobic digestion reactor.

Throughout the 24-day period, the reactor performance was assessed on days 1, 5, 9, 13, 19, and 24 by monitoring sCOD, total suspended solids (TSS), VS, TVFA, and alkalinity 25. Volatile fatty acids and alkalinity key indicators of process stabilitywere determined using the Nordmann titration method 26.

Composting Reactor: Aerated Static Pile System

In the composting phase, dewatered and chemically conditioned primary and secondary sludges served as the base feedstock. Preparation involved:

Composting Reactor: Aerated Static Pile System

In the composting phase, dewatered and chemically conditioned primary and secondary sludges served as the base feedstock. Preparation involved:

- Moisture reduction: Solid concentration increased from 2–3% to ~15% using lime and ferric chloride coagulants, optimized via jar testing.

- Porosity enhancement: Addition of wood chips (1–2.5 cm) as bulking agents.

- C/N adjustment: Achieved in the range of 20–30 by adding sawdust 27.

- Microbial augmentation: Incorporation of recycled wood chips containing biofilms from mature compost 28.

- Reactor loading: The prepared mixture was placed in aerated static pile (ASP) reactors (Figure 3) 29.

.JPG)

Figure 3: Loading stages of the aerated static pile composting reactor.

The laboratory-scale composting setup comprised a vacuum pump, perforated polyethylene aeration pipes, drainage siphons, and a support plate. The reactor structure consisted (from bottom to top) of polyethylene plates, a base compost layer, aeration and drainage pipes, wood shavings to prevent clogging, the initial compost mix, a coarse compost cover for insulation, a vacuum pump for negative-pressure aeration, a drainage siphon for leachate collection, and a mature compost biofilter for exhaust purification.

Aeration was achieved by drawing air through the compost matrix using a vacuum pump, ensuring adequate oxygen transfer. Exhaust air containing dust and bioaerosols passed through the leachate siphon and compost biofilter before being released into the environment. The aeration rate was maintained between 0.6 and 1.8 m³ t⁻¹ DM day⁻¹, while the oxygen concentration at the pile surface was measured daily and adjusted according to temperature variations as indicators of microbial activity. A minimum oxygen concentration of 5% was maintained throughout the experiment.

The total active composting period was maintained for 30 d, followed by unloading and transfer of the compost to a curing container for an additional 30-day maturation period. During curing, the material was manually turned to avoid agglomeration. Parameters including temperature, moisture content, pH, TS, and VS were monitored periodically during both the active and curing phases. Figure 4 presents a schematic of the ASP composting system.

Aeration was achieved by drawing air through the compost matrix using a vacuum pump, ensuring adequate oxygen transfer. Exhaust air containing dust and bioaerosols passed through the leachate siphon and compost biofilter before being released into the environment. The aeration rate was maintained between 0.6 and 1.8 m³ t⁻¹ DM day⁻¹, while the oxygen concentration at the pile surface was measured daily and adjusted according to temperature variations as indicators of microbial activity. A minimum oxygen concentration of 5% was maintained throughout the experiment.

The total active composting period was maintained for 30 d, followed by unloading and transfer of the compost to a curing container for an additional 30-day maturation period. During curing, the material was manually turned to avoid agglomeration. Parameters including temperature, moisture content, pH, TS, and VS were monitored periodically during both the active and curing phases. Figure 4 presents a schematic of the ASP composting system.

.JPG)

Figure 4: Schematic of the aerated static pile sludge composting reactor during the thermophilic phase.

Results

Characterization of Raw Sludge from the South Tehran WWTP

The physicochemical properties of the primary and secondary sludges used in this study are presented in Table 2. The pH values were near neutral for both sludges. Secondary sludge exhibited a significantly higher total solids (TS) content (7.2 ± 0.4%) than primary sludge (2.5 ± 0.2%), indicating a greater concentration through the activated sludge process. The volatile solids-to-total solids (VS/TS) ratios were 83.78 ± 1.2% and 76.34 ± 1.5% for secondary and primary sludge, respectively, confirming their high organic content. Secondary sludge also showed higher concentrations of total volatile fatty acids (TVFA: 1220 ± 45 mg/L) and alkalinity (670 ± 25 mg/L as CaCO₃) than primary sludge (TVFA: 870 ± 35 mg/L; alkalinity: 469 ± 20 mg/L), reflecting its more advanced biological activity and buffering capacity.

Table 2: Qualitative characteristics of primary and secondary sludge from the South Wastewater Treatment Plant

| Parameter | Primary sludge | Secondary sludge |

| pH | 6.14 ± 0.15 | 7.25 ± 0.12 |

| Total solids (TS, %) | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 7.2 ± 0.4 |

| VS/TS ratio (%) | 76.34 ± 1.5 | 83.78 ± 1.2 |

| Total volatile fatty acids (TVFA, mg/L) | 870 ± 35 | 1220 ± 45 |

| Alkalinity (mg/L as CaCO₃) | 469 ± 20 | 670 ± 25 |

Performance of Anaerobic Digestion (AD)

Biogas Production

Biogas production was initiated on day 3, accelerated by day 7, and peaked between days 8 and 9, with a maximum daily yield of 350 ± 18 mL (Figure 5). The cumulative biogas production reached 5405 ± 210 mL over the 24-day period (Figure 6).

Biogas Production

Biogas production was initiated on day 3, accelerated by day 7, and peaked between days 8 and 9, with a maximum daily yield of 350 ± 18 mL (Figure 5). The cumulative biogas production reached 5405 ± 210 mL over the 24-day period (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Daily biogas production during anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludg.

Figure 6: Cumulative biogas production during anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludge.

Process Stability and Organic Matter Removal

The soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD) profile (Figure 7) showed an initial increase due to hydrolysis, peaking at 2850 ± 120 mg/L on day 5, and then declining to a final concentration of 1110 ± 65 mg/L by day 24, indicating effective substrate utilization. The VS/TS ratio decreased from an initial 80.1 ± 1.8% in the feed to 48.2 ± 2.1% in the digestate, corresponding to a volatile solids reduction (VSR) of 39.8 ± 1.5. The process pH remained stable between 7.6 and 8.2 (Figure 8). TVFA concentrations peaked at 1450 ± 60 mg/L on day 5 and subsequently declined (Figure 9), indicating a balanced conversion of acids to methane and confirming stable methanogenic activity.

The soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD) profile (Figure 7) showed an initial increase due to hydrolysis, peaking at 2850 ± 120 mg/L on day 5, and then declining to a final concentration of 1110 ± 65 mg/L by day 24, indicating effective substrate utilization. The VS/TS ratio decreased from an initial 80.1 ± 1.8% in the feed to 48.2 ± 2.1% in the digestate, corresponding to a volatile solids reduction (VSR) of 39.8 ± 1.5. The process pH remained stable between 7.6 and 8.2 (Figure 8). TVFA concentrations peaked at 1450 ± 60 mg/L on day 5 and subsequently declined (Figure 9), indicating a balanced conversion of acids to methane and confirming stable methanogenic activity.

Figure 7: Temporal variations in soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD) during anaerobic digestion.

Figure 8: pH variations during the anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludge.

Figure 9: Temporal variations in total volatile fatty acids (TVFA) during anaerobic digestion.

Pretreatment and Composting Feedstock Preparation

Chemical conditioning with ferric chloride (8.1% of dry solids) and lime (17.3% of dry solids) significantly improved dewaterability, increasing the total solids (TS) content of the sludge mixture from 6.7 ± 0.3% to 17.9 ± 0.6% (Table 3). The optimized compost feedstock consisted of dewatered sludge (55% dry weight), wood chips (35% dry weight) and sawdust (15% dry weight) The mixture had a bulk density of 584 ± 22 kg/m³, pH of 8.9 ± 0.2, TS of 37.93 ± 1.5%, VS of 78.5 ± 2.1%, C/N ratio of 28.47 ± 1.3, and an initial fecal coliform concentration of (4.3 ± 0.4) × 10⁵ MPN/g dry solids (Tables 4 & 5).

Chemical conditioning with ferric chloride (8.1% of dry solids) and lime (17.3% of dry solids) significantly improved dewaterability, increasing the total solids (TS) content of the sludge mixture from 6.7 ± 0.3% to 17.9 ± 0.6% (Table 3). The optimized compost feedstock consisted of dewatered sludge (55% dry weight), wood chips (35% dry weight) and sawdust (15% dry weight) The mixture had a bulk density of 584 ± 22 kg/m³, pH of 8.9 ± 0.2, TS of 37.93 ± 1.5%, VS of 78.5 ± 2.1%, C/N ratio of 28.47 ± 1.3, and an initial fecal coliform concentration of (4.3 ± 0.4) × 10⁵ MPN/g dry solids (Tables 4 & 5).

Table 3: Characteristics of sludge mixture before and after conditioning and dewatering

| Parameter | Value |

| TS of sludge mixture before anaerobic digestion (%) | 6.7 ± 0.3 |

| TS of conditioned and dewatered sludge before composting (%) | 17.9 ± 0.6 |

| Ferric chloride dosage (% of dry solids) | 8.1 |

| Lime dosage (% of dry solids) | 17.3 |

Chemical conditioning with ferric chloride (8.1% of dry solids) and lime (17.3% of dry solids) significantly improved dewaterability, increasing the total solids (TS) content of the sludge mixture from 6.7 ± 0.3% to 17.9 ± 0.6% (Table 3). The optimized compost feedstock consisted of dewatered sludge (55% dry weight), wood chips (35% dry weight) and sawdust (15% dry weight) The mixture had a bulk density of 584 ± 22 kg/m³, pH of 8.9 ± 0.2, TS of 37.93 ± 1.5%, VS of 78.5 ± 2.1%, C/N ratio of 28.47 ± 1.3, and an initial fecal coliform concentration of (4.3 ± 0.4) × 10⁵ MPN/g dry solids (Tables 4 & 5).

Performance of Aerated Static Pile (ASP) Composting

Temperature and Process Progression

The composting temperature followed a typical pattern, reaching the thermophilic phase ( > 55°C) within 48 h and maintaining temperatures above 55°C for six consecutive days, with a peak of 65.2 ± 2.1°C (Figure 10). This sustained thermophilic period is critical for the inactivation of pathogens.

Performance of Aerated Static Pile (ASP) Composting

Temperature and Process Progression

The composting temperature followed a typical pattern, reaching the thermophilic phase ( > 55°C) within 48 h and maintaining temperatures above 55°C for six consecutive days, with a peak of 65.2 ± 2.1°C (Figure 10). This sustained thermophilic period is critical for the inactivation of pathogens.

Figure 10: Temperature profile during the rapid phase of sludge composting in a statically aerated pile reactor.

Physicochemical Evolution

The pH decreased from an initial 8.9 ± 0.2 to 7.8 ± 0.15 during the first week due to acid formation, then stabilized around neutral values by day 14, reaching 7.0 ± 0.1 by day 30 (Figure 11). During the 30-day composting period, the moisture content of the pile steadily declined owing to microbial activity and the heat generated within the system. To ensure optimal conditions for biological decomposition, the internal moisture level was regularly adjusted to 60% by adding water throughout the process.

The pH decreased from an initial 8.9 ± 0.2 to 7.8 ± 0.15 during the first week due to acid formation, then stabilized around neutral values by day 14, reaching 7.0 ± 0.1 by day 30 (Figure 11). During the 30-day composting period, the moisture content of the pile steadily declined owing to microbial activity and the heat generated within the system. To ensure optimal conditions for biological decomposition, the internal moisture level was regularly adjusted to 60% by adding water throughout the process.

Figure 11: pH variations during the rapid phase of sludge composting in a statically aerated pile reactor.

Compost Stabilization and Quality

The optimized compost mixture comprised dewatered sludge (55%), wood chips (35%), and sawdust (15%) on a dry-weight basis (Table 4). This composition achieved a suitable texture, porosity, and nutrient balance, promoting aeration and microbial activity. The physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of the initial composting mixture are summarized in Table 5, showing a bulk density of 584 kg/m³, pH of 8.9, total solids of 37.93%, volatile solids of 78.5%, and C/N ratio of 28.47. The initial fecal coliform concentration (4.3 × 10⁵ MPN/g dry solids) indicated the necessity of thermal sanitization during composting.

The optimized compost mixture comprised dewatered sludge (55%), wood chips (35%), and sawdust (15%) on a dry-weight basis (Table 4). This composition achieved a suitable texture, porosity, and nutrient balance, promoting aeration and microbial activity. The physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of the initial composting mixture are summarized in Table 5, showing a bulk density of 584 kg/m³, pH of 8.9, total solids of 37.93%, volatile solids of 78.5%, and C/N ratio of 28.47. The initial fecal coliform concentration (4.3 × 10⁵ MPN/g dry solids) indicated the necessity of thermal sanitization during composting.

Table 4: Optimized proportions and characteristics of sludge compost mixture

| Material | Optimal dry weight fraction (%) |

Dry solids content (%) |

Density (g/cm³) |

Volatile solids (%) |

| Dewatered sludge | 55 | 20 | 1.02 | 75 |

| Wood chips | 35 | 80 | 0.22 | 78 |

| Sawdust | 15 | 90 | 0.35 | 86 |

Table 5: Physicochemical and microbiological properties of the initial sludge compost mixture

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

| Bulk density | kg/m³ | 584 |

| pH | – | 8.9 |

| Total solids (TS) | % | 37.93 |

| Volatile solids (VS) | % | 78.5 |

| C/N ratio | – | 28.47 |

| Fecal coliforms | MPN/g dry solids | 4.3 × 10⁵ |

Table 4: Physical and microbiological properties of compost product at different composting stages

| Parameter | After rapid phase | After curing phase |

| Bulk density (kg/m³) | 570 ± 15 | 480.33 ± 12 |

| pH | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 7.23 ± 0.08 |

| Dry solids (%) | 60.1 ± 1.5 | 69.3 ± 1.8 |

| Volatile solids (% of TS) | 44.2 ± 1.2 | 37.1 ± 1.0 |

| Fecal coliforms (log MPN/g dry solids) | 2.36 ± 0.12 | < 1.0 (BDL*) |

*BDL: Below Detection Limit.

As presented in Table 4, the compost showed clear signs of its stabilization and maturation. The bulk density decreased from 570 ± 15 kg/m³ after the rapid phase to 480.33 ± 12 kg/m³ after curing. The dry solid content increased from 60.1 ± 1.5% to 69.3 ± 1.8%, whereas the volatile solid (VS) content decreased from 44.2 ± 1.2% to 37.1 ± 1.0% of TS, indicating significant organic matter mineralization (Figures 12 & 13).

Figure 12: Average weight percentage of dry solids.

Figure 13: Average weight percentage of organic solids to dry solids (VS/TS).

Fecal coliform counts were reduced from log 3.14 ± 0.15 MPN/g to log 2.36 ± 0.12 MPN/g after the rapid phase, and further to below the detection limit ( < 1.0 log MPN/g) after the 30-day curing period (Figure 14), representing a reduction of more than 3-log units. This reduction meets the pathogen inactivation requirement for USEPA Class A biosolids (fecal coliforms < 1000 MPN/g or < 3 log MPN/g) and aligns with the hygienic safety criteria outlined in international compost quality guidelines (e.g., WHO and European standards). While this study confirms hygienic safety and organic matter stabilization, a complete agronomic evaluation, including an analysis of primary nutrients (N-P-K), micropollutants, and potential contaminants such as heavy metals, was beyond its scope. Such comprehensive characterization is recommended for future studies to fully validate the quality and safety of compost for specific agricultural applications.

Pathogen Inactivation and Comparison with Standards

Pathogen Inactivation and Comparison with Standards

Figure 14: Reduction in fecal coliform counts during different stages of sludge composting.

Discussion

Qualitative Analysis of Wastewater Sludge from the South Tehran WWTP

The physicochemical characteristics of the primary and secondary sludges (Table 2) provided a crucial baseline for the comparative stabilization study. The near-neutral pH and higher TS, VS/TS ratio, and alkalinity in the secondary sludge are consistent with its origin from the activated sludge process, where microbial biomass accumulates and consumes volatile fatty acids (VFAs), generating bicarbonate and increasing the buffering capacity 30, 31. The elevated TVFA levels in primary sludge (870 mg/L), compared to secondary sludge, align with its composition, which is rich in readily hydrolyzable organic substrates such as carbohydrates and proteins 32-34. This distinction is significant, as the higher biodegradability potential of primary sludge, indicated by its TVFA content, likely contributed to the rapid initial biogas production observed in the AD reactors.

Performance Evaluation of Anaerobic Digestion

The biogas production profile observed in this study (Figures 5 and 6) followed a classic trend for batch mesophilic digestion. The lag phase, peak production around days 8-9, and subsequent decline correspond to the sequential establishment of hydrolytic, acidogenic, and methanogenic microbial communities, culminating in the depletion of readily degradable substrates 35, 36. The cumulative yield of 5405 mL and 40% volatile solids reduction (VSR) are within the typical range reported for sludge digestion under similar conditions 37, 38. The stability of the process was confirmed by the pH profile (Figure 8), which remained within the optimal range for methanogens (7.6-8.2), and the TVFA dynamics (Figure 9). The transient peak and subsequent decline in TVFAs, alongside stable alkalinity, indicate a well-balanced system in which acid production is efficiently coupled to methane generation, preventing inhibitory acidification 39, 40. The continuous decrease in sCOD (Figure 7) further corroborates the effective removal and conversion of organic carbon.

Optimization and Performance of Aerated Static Pile Composting

Successful composting of high-moisture sludge requires effective pretreatment. Chemical conditioning with FeCl₃ and lime increased the feed TS to ~18% (Table 3), which, combined with bulking agents (wood chips and sawdust), created a matrix with a suitable structure, porosity, and C/N ratio (Tables 4 and 5) 41, 42. This preparation was critical for enabling effective aeration of the mixture.

The operational data demonstrated a robust composting process. The temperature profile (Figure 10) shows a rapid ascent to and sustained thermophilic conditions (>55°C for six consecutive days), which is the key driver for pathogen inactivation and rapid decomposition of organic matter 29. The observed pH evolution (Figure 11) initial drop due to acidogenesis followed by a rise during the thermophilic and curing phases is characteristic of successful composting, reflecting the consumption of VFAs and the mineralization of nitrogenous compounds 43. The concomitant increase in dry solids (Figure 12) was a direct result of microbial heat generation and controlled aeration.

Most importantly, the ASP process achieved a >3-log reduction in fecal coliforms, reducing their counts to below the detection limit after curing (Figure 14, Table 4). This performance meets the stringent requirements for USEPA Class A biosolids 44. Concurrently, the VS content decreased from 78.5% in the feedstock to 37.1% in the cured compost (Figure 13, Table 4), indicating a high degree of organic matter stabilization and humification. The near-neutral pH, reduced bulk density, and low moisture content of the final product are indicators of compost maturity and suitability for soil application 45, 46. It is acknowledged that a full agronomic profile, including NPK content and heavy metal concentrations, is necessary to complete the quality assessment for specific end uses, and this is recommended for future work.

Comparative Analysis of AD and ASP Composting Efficiency

A direct comparison of the results of this study revealed distinct and complementary profiles for AD and ASP composting, each excelling in different aspects of sludge stabilization.

* Organic Stabilization vs. Energy Recovery: The core function of AD is the conversion of organic matter into biogas. Our results showed that a 40% VSR was achieved and 5405 mL of biogas was produced, effectively recovering energy from the sludge. In contrast, ASP composting is an oxidative process that focuses on organic matter stabilization and humification. It achieved a superior > 50% reduction in VS content (from 78.5% to 37.1%), producing a stabilized organic soil amendment but yielding no direct energy recovery.

* Hygienic Safety (Pathogen Inactivation): This study highlights a critical operational difference. The ASP process, with its sustained thermophilic phase, reduced fecal coliforms by over 3-log units, producing a sanitized product that met USEPA Class A standards. The mesophilic AD process, operating at 35°C, achieved only partial pathogen reduction, resulting in a digestate that would typically be classified as Class B biosolids, restricting its use to non-food crop agriculture or land reclamation 44. This is a decisive advantage for ASP composting when public health protection and agricultural versatility are the priorities.

* Process Stability and Product: AD requires careful monitoring of parameters such as pH, TVFA, and alkalinity (Figures 8 and 9) to maintain the delicate balance between microbial consortia. ASP composting requires moisture and aeration management, it demonstrated robust inherent stability through its self-heating nature and produced a physically stable, humus-like compost.

* Economic and Contextual Implications: The findings align with the established techno-economic understanding of these technologies 47-50. AD, with its energy output, offers better economic returns for large, centralized facilities such as the South Tehran WWTP, where capital investment can be justified and energy has market value. ASP composting, with its lower capital and operational complexity, presents a highly viable alternative for smaller plants, decentralized operations, or regions where the demand for high-quality, safe organic compost outweighs the need for on-site energy production.

In conclusion, this comparative evaluation demonstrates that the choice between mesophilic AD and ASP composting is not a matter of which technology is universally superior but rather which is more appropriate for a given context. AD is the optimal pathway when renewable energy recovery is the primary objective of a large-scale operation. ASP composting is the preferred technology when the goal is to produce a hygienically safe, Class A, soil-enhancing product with lower infrastructure demands, making it particularly suitable for enhancing sustainability in resource-conscious environments.

The Aerated Static Pile (ASP) composting method achieved significant pathogen reduction, yielding mature, nutrient-rich compost suitable for safe agricultural applications. Economically, ASP composting is more advantageous for small-scale plants because of lower capital investment, whereas anaerobic digestion remains preferable for large-scale wastewater treatment facilities 51, 52.

Conclusion

This study provides a technical comparative evaluation of two primary sludge-stabilization methods. Mesophilic anaerobic digestion proved to be an efficient solution for energy recovery, yielding 5405 mL of biogas and achieving a 40% reduction in volatile solids (VS). However, the final digestate was classified as a Class B biosolid in terms of hygienic safety. In contrast, aerated static pile composting produced a stable, pathogen-free organic amendment that met Class A standards, as demonstrated by a greater than 3-log reduction in fecal coliforms and an over 50% reduction in volatile solids. The choice between these two technologies depends on local operational priorities: whether to pursue large-scale energy recovery or produce a high-quality, safe soil conditioner with lower capital costs. The findings suggest that aerated static pile composting is an effective and sustainable alternative, particularly for smaller facilities or regions with a high demand for organic fertilizers. We recommend that future studies investigate the physicochemical properties of compost (e.g., nutrient content N-P-K) and analyze metal/micropollutants.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Iran University of Medical Sciences for awarding the Research Grant Scheme (1401-4-75-24480) for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This studywas supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences [1401-4-75-24480].

Ethical Considerations

This study does not involve human participants or animals. Therefore, ethical approval and informed consent were not required.

Code of Ethics

The authors confirm that this study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of research integrity and responsible reporting. This study did not involve any moral concernsand was approved by the Ethics Committee under approval code: IR.IUMS.REC.1402.027

Authors' Contributions

Mohammad Hasan Kowsari: Data curation; Visualization; Writing - original draft. Mojtaba Yeganeh: Investigation; Writing - review & editing. Mohsen Ansari: Methodology; Writing - review & editing. Behnaz Abdolahi Nejad: Resources; Writing - original draft. Masoumeh Hasham Firooz: Validation; Writing - original draft. Mahdi Farzadkia: Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Supervision; Writing - review & editing.

This is an Open-Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work for commercial use.

Reference

1. Castellano-Hinojosa A, Armato C, Pozo C, et al. New concepts in anaerobic digestion processes: recent advances and biological aspects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102(12):5065-76.

2. Ghoreishi B, Aslani H, Shaker Khatibi M, et al. Pollution potential and ecological risk of heavy metals in municipal wastewater treatment plants sludge. Iranian Journal of Health and Environment. 2020;13(1):87.

3. Appels L, Baeyens J, Degrève J, et al. Principles and potential of the anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2008;34(6):755-81.

4. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the safe use of wastewater, excreta and greywater: World Health Organization; 2006.

5. Kumar A, Rani A, Choudhary M. Anaerobic digestion for climate change mitigation: a review. Biotechnological Innovations for Environmental Bioremediation. 2022: 83-118.

6. Sadeghi Looyeh N, Rafiee S, Aghbashloo M, et al. Mathematical modeling of energy and emissions in the co-gasification of sewage sludge and municipal solid waste: a case study of Tehran. Journal of Natural Environment.2025; 78 (Monitoring and Management of Natural Environmental Pollutants):25565.

7. Scrinzi D, Ferrentino R, Baù E, et al. Sewage sludge management at district level: reduction and nutrients recovery via hydrothermal carbonization. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2023;14(8):2505-17.

8. Domini M, Abbà A, Bertanza G. Analysis of the variation of costs for sewage sludge transport, recovery and disposal in Northern Italy: a recent survey (2015–2021). Water Sci Technol. 2022;85(4):1167-75.

9. Trujillo-Reyes Á, Serrano A, Cubero-Cardoso J, et al. Does seasonality of feedstock affect anaerobic digestion?. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(21):26905-14.

10. McCARTY PL. Anaerobic waste treatment fundamentals. Public Works. 1964;95(9).

11. Appels L, Lauwers J, Degrève J, et al. Anaerobic digestion in global bio-energy production: potential and research challenges. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2011; 15(9): 4295-301.

12. Weiland P. Biogas production: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85(4):849-60.

13. Wang H, Zhou Q. Dominant factors analyses and challenges of anaerobic digestion under cold environments. J Environ Manage. 2023;348:119378.

14. Vráblová M, Smutná K, Chamrádová K, et al. Co-composting of sewage sludge as an effective technology for the production of substrates with reduced content of pharmaceutical residues. Sci Total Environ. 2024;915:169818.

15. Epstein E. The science of composting: CRC press; 2017.

16. Ahmed HK, Fawy HA, Abdel-Hady E. Study of sewage sludge use in agriculture and its effect on plant and soil. Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America. 2010;1(5):1044-9.

17. de Castro e Silva HL, Barros RM, dos Santos IFS, et al. Addition of iron ore tailings to increase the efficiency of anaerobic digestion of swine manure: ecotoxicological and elemental analyses in digestates. Environ Dev Sustain. 2024;26(6):15361-79.

18. Garcia C, Hernandez T, Costa F. Microbial activity in soils under Mediterranean environmental conditions. Soil Biol Biochem. 1994;26(9):1185-91.

19. Tester CF. Organic amendment effects on physical and chemical properties of a sandy soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1990;54(3):827-31.

20. Manea EE, Bumbac C. Sludge composting—is this a viable solution for wastewater sludge management?. Water. 2024;16(16).

21. Zhu X, Xu Y, Zhen G, et al. Effective multipurpose sewage sludge and food waste reduction strategies: a focus on recent advances and future perspectives. Chemosphere. 2023;311:136670.

22. Tsigkou K, Zagklis D, Tsafrakidou P, et al. Composting of anaerobic sludge from the co-digestion of used disposable nappies and expired food products. Waste Management. 2020;118:655-66.

23. Kliopova I, Stunžėnas E, Kruopienė J, et al. Environmental and economic performance of sludge composting optimization alternatives: a case study for thermally hydrolyzed anaerobically digested sludge. Water. 2022;14(24):4102.

24. Rice EW, Baird RB, Eaton AD, et al. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater 2012.

25. American Public Health Association. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater: American public health association.; 1926.

26. Lili M, Biró G, Sulyok E, et al. Novel approach on the basis of FOS/TAC method. Analele Universităţ ii din Oradea, Fascicula Protecţia Mediului. 2011;17:713-8.

27. De Bertoldi M, editor. The science of composting: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013.

28. Gurjar B, Tyagi VK. Sludge management: CRC Press; 2017.

29. Haug R. The practical handbook of compost engineering. Routledge; 2018.

30. Gerardi MH. The microbiology of anaerobic digesters. John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

31. Metcalf E, Tchobanoglous G, Stensel H, et al. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery McGraw-Hill. New York, NY, USA. 2014.

32. Ucisik AS, Henze M. Biological hydrolysis and acidification of sludge under anaerobic conditions: the effect of sludge type and origin on the production and composition of volatile fatty acids. Water Res. 2008;42(14):3729-38.

33. Parkin GF, Owen WF. Fundamentals of anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludges. J Environ Eng. 1986;112(5):867-920.

34. Fothergill S, Mavinic D. VFA production in thermophilic aerobic digestion of municipal sludges. J Environ Eng. 2000;126(5):389-96.

35. Rocha ME, Lazarino TC, Oliveira G, et al. Analysis of biogas production from sewage sludge combining BMP experimental assays and the ADM1 model. PeerJ. 2024;12:e16720.

36. Hallaji SM, Kuroshkarim M, Moussavi SP. Enhancing methane production using anaerobic co-digestion of waste activated sludge with combined fruit waste and cheese whey. BMC Biotechnol. 2019;19(1):19.

37. Nguyen D, Nitayavardhana S, Sawatdeenarunat C, et al. Biogas production by anaerobic digestion: status and perspectives. Biofuels: alternative feedstocks and conversion processes for the production of liquid and gaseous biofuels: Elsevier; 2019pp. 763-78. Academic Press.

38. Wijekoon KC, Visvanathan C, Abeynayaka A. Effect of organic loading rate on VFA production, organic matter removal and microbial activity of a two-stage thermophilic anaerobic membrane bioreactor. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(9):5353-60.

39. Boe K, Batstone DJ, Steyer J-P, et al. State indicators for monitoring the anaerobic digestion process. Water Res. 2010;44(20):5973-80.

40. Jia R, Song Y-C, An Z, et al. A new comprehensive indicator for monitoring anaerobic digestion: a principal component analysis approach. Processes. 2023;12(1):59.

41. Liang Y, Wang R, Sun W, et al. Advances in chemical conditioning of residual activated sludge in China. Water. 2023;15(2):345.

42. Wu W, Zhou Z, Yang J, et al. Insights into conditioning of landfill sludge by FeCl3 and lime. Water Res. 2019;160:167-77.

43. Epstein E. Industrial composting. Environmental engineering and facilities management. New York: Taylor and Francis Group. 2011.

44. Wainaina S, Awasthi MK, Sarsaiya S, et al. Resource recovery and circular economy from organic solid waste using aerobic and anaerobic digestion technologies. Bioresour Technol. 2020;301:122778.

45. Yang M, Guo Y, Yang F, et al. Dynamic changes in and correlations between microbial communities and physicochemical properties during the composting of cattle manure with Penicillium oxalicum. BMC Microbiol. 2024;24(1):301.

46. Hassen A, Belguith K, Jedidi N, et al. Microbial characterization during composting of municipal solid waste. Bioresour Technol. 2001;80(3):217-25.

47. Rajabi Hamedani S, Villarini M, Colantoni A, et al. Environmental and economic analysis of an anaerobic co-digestion power plant integrated with a compost plant. Energies. 2020;13(11):2724.

48. Murphy JD, Power NM. A technical, economic and environmental comparison of composting and anaerobic digestion of biodegradable municipal waste. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A. 2006;41(5):865-79.

49. Lin L, Xu F, Ge X, et al. Improving the sustainability of organic waste management practices in the food-energy-water nexus: a comparative review of anaerobic digestion and composting. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;89:151-67.

50. Alam S, Rokonuzzaman M, Rahman KS, et al. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of organic municipal solid waste for energy production. Heliyon. 2024;10(11).

51. Hudcová H, Vymazal J, Rozkošný M. Present restrictions of sewage sludge application in agriculture within the European :union:. Soil & Water Research. 2019;14(2).

52. Tizghadam M, Dagot C, Baudu M. Wastewater treatment in a hybrid activated sludge baffled reactor. J Hazard Mater. 2008;154(1-3):550-7.

Qualitative Analysis of Wastewater Sludge from the South Tehran WWTP

The physicochemical characteristics of the primary and secondary sludges (Table 2) provided a crucial baseline for the comparative stabilization study. The near-neutral pH and higher TS, VS/TS ratio, and alkalinity in the secondary sludge are consistent with its origin from the activated sludge process, where microbial biomass accumulates and consumes volatile fatty acids (VFAs), generating bicarbonate and increasing the buffering capacity 30, 31. The elevated TVFA levels in primary sludge (870 mg/L), compared to secondary sludge, align with its composition, which is rich in readily hydrolyzable organic substrates such as carbohydrates and proteins 32-34. This distinction is significant, as the higher biodegradability potential of primary sludge, indicated by its TVFA content, likely contributed to the rapid initial biogas production observed in the AD reactors.

Performance Evaluation of Anaerobic Digestion

The biogas production profile observed in this study (Figures 5 and 6) followed a classic trend for batch mesophilic digestion. The lag phase, peak production around days 8-9, and subsequent decline correspond to the sequential establishment of hydrolytic, acidogenic, and methanogenic microbial communities, culminating in the depletion of readily degradable substrates 35, 36. The cumulative yield of 5405 mL and 40% volatile solids reduction (VSR) are within the typical range reported for sludge digestion under similar conditions 37, 38. The stability of the process was confirmed by the pH profile (Figure 8), which remained within the optimal range for methanogens (7.6-8.2), and the TVFA dynamics (Figure 9). The transient peak and subsequent decline in TVFAs, alongside stable alkalinity, indicate a well-balanced system in which acid production is efficiently coupled to methane generation, preventing inhibitory acidification 39, 40. The continuous decrease in sCOD (Figure 7) further corroborates the effective removal and conversion of organic carbon.

Optimization and Performance of Aerated Static Pile Composting

Successful composting of high-moisture sludge requires effective pretreatment. Chemical conditioning with FeCl₃ and lime increased the feed TS to ~18% (Table 3), which, combined with bulking agents (wood chips and sawdust), created a matrix with a suitable structure, porosity, and C/N ratio (Tables 4 and 5) 41, 42. This preparation was critical for enabling effective aeration of the mixture.

The operational data demonstrated a robust composting process. The temperature profile (Figure 10) shows a rapid ascent to and sustained thermophilic conditions (>55°C for six consecutive days), which is the key driver for pathogen inactivation and rapid decomposition of organic matter 29. The observed pH evolution (Figure 11) initial drop due to acidogenesis followed by a rise during the thermophilic and curing phases is characteristic of successful composting, reflecting the consumption of VFAs and the mineralization of nitrogenous compounds 43. The concomitant increase in dry solids (Figure 12) was a direct result of microbial heat generation and controlled aeration.

Most importantly, the ASP process achieved a >3-log reduction in fecal coliforms, reducing their counts to below the detection limit after curing (Figure 14, Table 4). This performance meets the stringent requirements for USEPA Class A biosolids 44. Concurrently, the VS content decreased from 78.5% in the feedstock to 37.1% in the cured compost (Figure 13, Table 4), indicating a high degree of organic matter stabilization and humification. The near-neutral pH, reduced bulk density, and low moisture content of the final product are indicators of compost maturity and suitability for soil application 45, 46. It is acknowledged that a full agronomic profile, including NPK content and heavy metal concentrations, is necessary to complete the quality assessment for specific end uses, and this is recommended for future work.

Comparative Analysis of AD and ASP Composting Efficiency

A direct comparison of the results of this study revealed distinct and complementary profiles for AD and ASP composting, each excelling in different aspects of sludge stabilization.

* Organic Stabilization vs. Energy Recovery: The core function of AD is the conversion of organic matter into biogas. Our results showed that a 40% VSR was achieved and 5405 mL of biogas was produced, effectively recovering energy from the sludge. In contrast, ASP composting is an oxidative process that focuses on organic matter stabilization and humification. It achieved a superior > 50% reduction in VS content (from 78.5% to 37.1%), producing a stabilized organic soil amendment but yielding no direct energy recovery.

* Hygienic Safety (Pathogen Inactivation): This study highlights a critical operational difference. The ASP process, with its sustained thermophilic phase, reduced fecal coliforms by over 3-log units, producing a sanitized product that met USEPA Class A standards. The mesophilic AD process, operating at 35°C, achieved only partial pathogen reduction, resulting in a digestate that would typically be classified as Class B biosolids, restricting its use to non-food crop agriculture or land reclamation 44. This is a decisive advantage for ASP composting when public health protection and agricultural versatility are the priorities.

* Process Stability and Product: AD requires careful monitoring of parameters such as pH, TVFA, and alkalinity (Figures 8 and 9) to maintain the delicate balance between microbial consortia. ASP composting requires moisture and aeration management, it demonstrated robust inherent stability through its self-heating nature and produced a physically stable, humus-like compost.

* Economic and Contextual Implications: The findings align with the established techno-economic understanding of these technologies 47-50. AD, with its energy output, offers better economic returns for large, centralized facilities such as the South Tehran WWTP, where capital investment can be justified and energy has market value. ASP composting, with its lower capital and operational complexity, presents a highly viable alternative for smaller plants, decentralized operations, or regions where the demand for high-quality, safe organic compost outweighs the need for on-site energy production.

In conclusion, this comparative evaluation demonstrates that the choice between mesophilic AD and ASP composting is not a matter of which technology is universally superior but rather which is more appropriate for a given context. AD is the optimal pathway when renewable energy recovery is the primary objective of a large-scale operation. ASP composting is the preferred technology when the goal is to produce a hygienically safe, Class A, soil-enhancing product with lower infrastructure demands, making it particularly suitable for enhancing sustainability in resource-conscious environments.

The Aerated Static Pile (ASP) composting method achieved significant pathogen reduction, yielding mature, nutrient-rich compost suitable for safe agricultural applications. Economically, ASP composting is more advantageous for small-scale plants because of lower capital investment, whereas anaerobic digestion remains preferable for large-scale wastewater treatment facilities 51, 52.

Conclusion

This study provides a technical comparative evaluation of two primary sludge-stabilization methods. Mesophilic anaerobic digestion proved to be an efficient solution for energy recovery, yielding 5405 mL of biogas and achieving a 40% reduction in volatile solids (VS). However, the final digestate was classified as a Class B biosolid in terms of hygienic safety. In contrast, aerated static pile composting produced a stable, pathogen-free organic amendment that met Class A standards, as demonstrated by a greater than 3-log reduction in fecal coliforms and an over 50% reduction in volatile solids. The choice between these two technologies depends on local operational priorities: whether to pursue large-scale energy recovery or produce a high-quality, safe soil conditioner with lower capital costs. The findings suggest that aerated static pile composting is an effective and sustainable alternative, particularly for smaller facilities or regions with a high demand for organic fertilizers. We recommend that future studies investigate the physicochemical properties of compost (e.g., nutrient content N-P-K) and analyze metal/micropollutants.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Iran University of Medical Sciences for awarding the Research Grant Scheme (1401-4-75-24480) for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This studywas supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences [1401-4-75-24480].

Ethical Considerations

This study does not involve human participants or animals. Therefore, ethical approval and informed consent were not required.

Code of Ethics

The authors confirm that this study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of research integrity and responsible reporting. This study did not involve any moral concernsand was approved by the Ethics Committee under approval code: IR.IUMS.REC.1402.027

Authors' Contributions

Mohammad Hasan Kowsari: Data curation; Visualization; Writing - original draft. Mojtaba Yeganeh: Investigation; Writing - review & editing. Mohsen Ansari: Methodology; Writing - review & editing. Behnaz Abdolahi Nejad: Resources; Writing - original draft. Masoumeh Hasham Firooz: Validation; Writing - original draft. Mahdi Farzadkia: Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Supervision; Writing - review & editing.

This is an Open-Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work for commercial use.

Reference

1. Castellano-Hinojosa A, Armato C, Pozo C, et al. New concepts in anaerobic digestion processes: recent advances and biological aspects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102(12):5065-76.

2. Ghoreishi B, Aslani H, Shaker Khatibi M, et al. Pollution potential and ecological risk of heavy metals in municipal wastewater treatment plants sludge. Iranian Journal of Health and Environment. 2020;13(1):87.

3. Appels L, Baeyens J, Degrève J, et al. Principles and potential of the anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2008;34(6):755-81.

4. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the safe use of wastewater, excreta and greywater: World Health Organization; 2006.

5. Kumar A, Rani A, Choudhary M. Anaerobic digestion for climate change mitigation: a review. Biotechnological Innovations for Environmental Bioremediation. 2022: 83-118.

6. Sadeghi Looyeh N, Rafiee S, Aghbashloo M, et al. Mathematical modeling of energy and emissions in the co-gasification of sewage sludge and municipal solid waste: a case study of Tehran. Journal of Natural Environment.2025; 78 (Monitoring and Management of Natural Environmental Pollutants):25565.

7. Scrinzi D, Ferrentino R, Baù E, et al. Sewage sludge management at district level: reduction and nutrients recovery via hydrothermal carbonization. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2023;14(8):2505-17.

8. Domini M, Abbà A, Bertanza G. Analysis of the variation of costs for sewage sludge transport, recovery and disposal in Northern Italy: a recent survey (2015–2021). Water Sci Technol. 2022;85(4):1167-75.

9. Trujillo-Reyes Á, Serrano A, Cubero-Cardoso J, et al. Does seasonality of feedstock affect anaerobic digestion?. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(21):26905-14.

10. McCARTY PL. Anaerobic waste treatment fundamentals. Public Works. 1964;95(9).

11. Appels L, Lauwers J, Degrève J, et al. Anaerobic digestion in global bio-energy production: potential and research challenges. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2011; 15(9): 4295-301.

12. Weiland P. Biogas production: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85(4):849-60.

13. Wang H, Zhou Q. Dominant factors analyses and challenges of anaerobic digestion under cold environments. J Environ Manage. 2023;348:119378.

14. Vráblová M, Smutná K, Chamrádová K, et al. Co-composting of sewage sludge as an effective technology for the production of substrates with reduced content of pharmaceutical residues. Sci Total Environ. 2024;915:169818.

15. Epstein E. The science of composting: CRC press; 2017.

16. Ahmed HK, Fawy HA, Abdel-Hady E. Study of sewage sludge use in agriculture and its effect on plant and soil. Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America. 2010;1(5):1044-9.

17. de Castro e Silva HL, Barros RM, dos Santos IFS, et al. Addition of iron ore tailings to increase the efficiency of anaerobic digestion of swine manure: ecotoxicological and elemental analyses in digestates. Environ Dev Sustain. 2024;26(6):15361-79.

18. Garcia C, Hernandez T, Costa F. Microbial activity in soils under Mediterranean environmental conditions. Soil Biol Biochem. 1994;26(9):1185-91.

19. Tester CF. Organic amendment effects on physical and chemical properties of a sandy soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1990;54(3):827-31.

20. Manea EE, Bumbac C. Sludge composting—is this a viable solution for wastewater sludge management?. Water. 2024;16(16).

21. Zhu X, Xu Y, Zhen G, et al. Effective multipurpose sewage sludge and food waste reduction strategies: a focus on recent advances and future perspectives. Chemosphere. 2023;311:136670.

22. Tsigkou K, Zagklis D, Tsafrakidou P, et al. Composting of anaerobic sludge from the co-digestion of used disposable nappies and expired food products. Waste Management. 2020;118:655-66.

23. Kliopova I, Stunžėnas E, Kruopienė J, et al. Environmental and economic performance of sludge composting optimization alternatives: a case study for thermally hydrolyzed anaerobically digested sludge. Water. 2022;14(24):4102.

24. Rice EW, Baird RB, Eaton AD, et al. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater 2012.

25. American Public Health Association. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater: American public health association.; 1926.

26. Lili M, Biró G, Sulyok E, et al. Novel approach on the basis of FOS/TAC method. Analele Universităţ ii din Oradea, Fascicula Protecţia Mediului. 2011;17:713-8.

27. De Bertoldi M, editor. The science of composting: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013.

28. Gurjar B, Tyagi VK. Sludge management: CRC Press; 2017.

29. Haug R. The practical handbook of compost engineering. Routledge; 2018.

30. Gerardi MH. The microbiology of anaerobic digesters. John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

31. Metcalf E, Tchobanoglous G, Stensel H, et al. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery McGraw-Hill. New York, NY, USA. 2014.

32. Ucisik AS, Henze M. Biological hydrolysis and acidification of sludge under anaerobic conditions: the effect of sludge type and origin on the production and composition of volatile fatty acids. Water Res. 2008;42(14):3729-38.

33. Parkin GF, Owen WF. Fundamentals of anaerobic digestion of wastewater sludges. J Environ Eng. 1986;112(5):867-920.

34. Fothergill S, Mavinic D. VFA production in thermophilic aerobic digestion of municipal sludges. J Environ Eng. 2000;126(5):389-96.

35. Rocha ME, Lazarino TC, Oliveira G, et al. Analysis of biogas production from sewage sludge combining BMP experimental assays and the ADM1 model. PeerJ. 2024;12:e16720.

36. Hallaji SM, Kuroshkarim M, Moussavi SP. Enhancing methane production using anaerobic co-digestion of waste activated sludge with combined fruit waste and cheese whey. BMC Biotechnol. 2019;19(1):19.

37. Nguyen D, Nitayavardhana S, Sawatdeenarunat C, et al. Biogas production by anaerobic digestion: status and perspectives. Biofuels: alternative feedstocks and conversion processes for the production of liquid and gaseous biofuels: Elsevier; 2019pp. 763-78. Academic Press.

38. Wijekoon KC, Visvanathan C, Abeynayaka A. Effect of organic loading rate on VFA production, organic matter removal and microbial activity of a two-stage thermophilic anaerobic membrane bioreactor. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(9):5353-60.

39. Boe K, Batstone DJ, Steyer J-P, et al. State indicators for monitoring the anaerobic digestion process. Water Res. 2010;44(20):5973-80.

40. Jia R, Song Y-C, An Z, et al. A new comprehensive indicator for monitoring anaerobic digestion: a principal component analysis approach. Processes. 2023;12(1):59.

41. Liang Y, Wang R, Sun W, et al. Advances in chemical conditioning of residual activated sludge in China. Water. 2023;15(2):345.

42. Wu W, Zhou Z, Yang J, et al. Insights into conditioning of landfill sludge by FeCl3 and lime. Water Res. 2019;160:167-77.

43. Epstein E. Industrial composting. Environmental engineering and facilities management. New York: Taylor and Francis Group. 2011.

44. Wainaina S, Awasthi MK, Sarsaiya S, et al. Resource recovery and circular economy from organic solid waste using aerobic and anaerobic digestion technologies. Bioresour Technol. 2020;301:122778.

45. Yang M, Guo Y, Yang F, et al. Dynamic changes in and correlations between microbial communities and physicochemical properties during the composting of cattle manure with Penicillium oxalicum. BMC Microbiol. 2024;24(1):301.

46. Hassen A, Belguith K, Jedidi N, et al. Microbial characterization during composting of municipal solid waste. Bioresour Technol. 2001;80(3):217-25.

47. Rajabi Hamedani S, Villarini M, Colantoni A, et al. Environmental and economic analysis of an anaerobic co-digestion power plant integrated with a compost plant. Energies. 2020;13(11):2724.

48. Murphy JD, Power NM. A technical, economic and environmental comparison of composting and anaerobic digestion of biodegradable municipal waste. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A. 2006;41(5):865-79.

49. Lin L, Xu F, Ge X, et al. Improving the sustainability of organic waste management practices in the food-energy-water nexus: a comparative review of anaerobic digestion and composting. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;89:151-67.

50. Alam S, Rokonuzzaman M, Rahman KS, et al. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of organic municipal solid waste for energy production. Heliyon. 2024;10(11).

51. Hudcová H, Vymazal J, Rozkošný M. Present restrictions of sewage sludge application in agriculture within the European :union:. Soil & Water Research. 2019;14(2).

52. Tizghadam M, Dagot C, Baudu M. Wastewater treatment in a hybrid activated sludge baffled reactor. J Hazard Mater. 2008;154(1-3):550-7.