Volume 10, Issue 4 (December 2025)

J Environ Health Sustain Dev 2025, 10(4): 2859-2869 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mulyasari T M, Mukono J, Sudiana I K, Ningrum P T. The Effect of Subacute Exposure to Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) Microplastics on Oxidative Stress and Membrane Damage in Alveolar Macrophage Cells of Rattus Norvegicus Wistar Strain. J Environ Health Sustain Dev 2025; 10 (4) :2859-2869

URL: http://jehsd.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-985-en.html

URL: http://jehsd.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-985-en.html

Department of Environmental Health, Politeknik Kesehatan Kemenkes Semarang, Indonesia

Keywords: Microplastic, Alveolar Macrophages, Superoxide Dismutase, F2 Isoprostanes, Oxidative Stress.

Full-Text [PDF 656 kb]

(37 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (209 Views)

.JPG)

Figure 1: FTIR spectrum of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) microplastic particles.

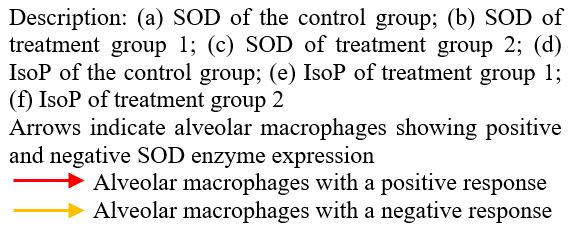

.JPG) Figure 3: Immunohistochemical expression of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages of Rattus norvegicus after 28 days of exposure to LDPE microplastics.

Figure 3: Immunohistochemical expression of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages of Rattus norvegicus after 28 days of exposure to LDPE microplastics.

Full-Text: (14 Views)

The Effect of Subacute Exposure to Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) Microplastics on Oxidative Stress and Membrane Damage in Alveolar Macrophage Cells of Rattus Norvegicus Wistar Strain

Tri Marthy Mulyasari 1*, Jojok Mukono 2, I Ketut Sudiana 3, Prehatin Trirahayu Ningrum 4

1 Department of Environmental Health, Politeknik Kesehatan Kemenkes Semarang, Indonesia.

2 Faculty of Public Health, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia.

3 Faculty of Medicine, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia.

4 Faculty of Public Health, University of Jember, Indonesia.

Tri Marthy Mulyasari 1*, Jojok Mukono 2, I Ketut Sudiana 3, Prehatin Trirahayu Ningrum 4

1 Department of Environmental Health, Politeknik Kesehatan Kemenkes Semarang, Indonesia.

2 Faculty of Public Health, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia.

3 Faculty of Medicine, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia.

4 Faculty of Public Health, University of Jember, Indonesia.

| A R T I C L E I N F O | ABSTRACT | |

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE | Introduction: Inhalation of microplastics (MPs) can damage lung tissue. Alveolar macrophages express superoxide dismutase (SOD) as a defensive response to foreign substances. Additionally, F2-isoprostane (IsoP) is a specific biomarker of oxidative stress induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS). This study aimed to analyze the effects of Mps inhalation on alveolar macrophages. Materials and Methods: This true experimental study employed a post-test-only control group design using 21 Wistar rats. MPs aerosols at concentrations of 1 mg/L/day and 2 mg/L/day were inhaled for 28 days. Airborne MPs were measured using passive sampling methods. SOD and IsoP expression levels were evaluated using immunohistochemistry, and their correlations with MPs levels were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation test. Results: The average level of MPs in the air chamber of treatment group 1 was 17.59 particles/unit chamber, and that of treatment group 2 was 35.95 particles/unit chamber. The average expression of SOD and IsoP in the 1 mg/L exposure samples was 15.16 cells/field of view and 17.54 cells/field of view, while in the 2 mg/L exposure samples, there were 10.63 cells/field of view and 23.28 cells/field of view. The effect of MPs levels in chamber air on the expression of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages in lung tissue was significant (p < 0.05). Conclusions: Subacute exposure to MPs causes oxidative stress and damage to the membrane of macrophage cells. The dose of exposure to MPs in the study may be higher than the presence of MPs in the air in reality. |

|

Article History: Received: 13 August 2025 Accepted: 20 October 2025 |

||

*Corresponding Author: Tri Marthy Mulyasari Email: tmmulyasari@poltekkes-smg.ac.id Tel: +62 85643222116 |

||

Keywords: Microplastic; Alveolar Macrophages; Superoxide Dismutase; F2 Isoprostanes; Oxidative Stress. |

Citation: Tri Marthy Mulyasari, Jojok Mukono, I Ketut Sudiana, et al. The Effect of Subacute Exposure to Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) Microplastics on Oxidative Stress and Membrane Damage in Alveolar Macrophage Cells of Rattus Norvegicus Wistar Strain. J Environ Health Sustain Dev. 2025; 10(4): 2859-69.

Introduction

Microplastics (MPs) have recently been recognized as emerging airborne contaminants with potential implications for human health. The extensive use of plastic materials in daily life has led to the release of MPs into both indoor and outdoor air environments. These particles, typically ranging from 0.1 µm to 5 mm in size 1, are generated through the physical, chemical, mechanical, and biological degradation of larger plastic items2. Based on their origin, MPs are classified as primary or secondary, and they appear morphologically as fragments, pellets, fibers, films, or foams3.

Several studies have confirmed the presence of airborne MPs in various areas. In Surabaya, Indonesia, their abundance reached 174.97 particles/m3/day, which was associated with heavy traffic4. In New Jersey, USA, indoor measurements showed high concentrations of polyethylene (PE) fibers, especially in residential areas, indicating that households are major sources of microplastic fibers5. Similar findings in Portugal reported an outdoor abundance of 6 fibers/m3, confirming that microplastics are widespread in the atmosphere6.

Airborne MPs may adversely affect the respiratory system6. Particles smaller than 16.8 µm can penetrate the lower respiratory tract, bypass mucociliary clearance, and accumulate in the alveolar region7. Once deposited, MPs can activate alveolar macrophages, which act as the first line of immune defense through phagocytosis8. This process stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals, potentially leading to oxidative stress and cellular damage9.

To counteract oxidative stress, cells express antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and catalase (CAT)10. However, excessive ROS production can overwhelm the antioxidant defenses, resulting in lipid peroxidation and the formation of biomarkers such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and isoprostanes (IsoP). Elevated levels of these metabolites indicate membrane damage and oxidative imbalance, which may contribute to inflammation and degenerative changes in the lung tissue11.

If oxidative stress leads to phospholipid damage in the cell membrane, it is indicated by the formation of MDA and IsoP as toxic byproducts12. IsoP is a specific product of arachidonic acid peroxidation, which occurs as a result of oxidative stress and cell membrane damage. An increase in IsoP metabolites indicates elevated oxidative stress in the body and may serve as an important biomarker for degenerative diseases13. Inhaled MPs can reach the alveoli and be phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages (AMs). Alveolar macrophages play a crucial role in responding to foreign particles and secreting inflammatory mediators to maintain homeostasis14. MPs trigger inflammatory reactions and oxidative stress, which may alter the expression of molecules associated with these processes, including IsoP. Excessive macrophage activation during inflammatory cell recruitment can lead to inflammation and damage to lung tissue8.

Although several studies have reported the presence and potential toxicity of airborne microplastics, limited research has focused on their specific effects on lung immune cells, particularly the alveolar macrophages. Previous studies have mainly examined oxidative stress markers, such as malondialdehyde (MDA); however, the combined expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and isoprostanes (IsoP) as indicators of oxidative stress and membrane damage in alveolar macrophages has not been investigated. Therefore, this study provides novel insights into the oxidative and inflammatory responses of alveolar macrophages following subacute exposure to low-density polyethylene (LDPE) microplastics. This study aimed to analyze the effects of subacute exposure to low-density polyethylene (LDPE) MPs on oxidative stress and membrane damage in alveolar macrophages of Rattus norvegicus Wistar strain.

Materials and Methods

This study was a true experimental study using a post-test-only control group design. The independent variable was the concentration of airborne MPs, and the dependent variables were SOD and IsoP expression. The study consisted of three groups: control (K), treatment 1 (P1), and treatment 2 (P2) groups.

Research ethics

Ethical approval was obtained for the use of experimental animals. The ethical clearance certificate (No. 1069/EA/KEPK/2023) was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health and Semarang Health Polytechnic.

Experimental animals

Healthy male Rattus norvegicus (Wistar strain) rats weighing 150 ± 20 g were used as the experimental animals. Animals that died during the study were excluded. The sample size was determined using the method described by Lemeshow15 with reference to previous studies. The parameters included the standard deviation of the control group (∑ = 0.53), Z½α = 1.96 (α = 0.05), Zβ = 1.64, and mean responses of µ₁ = 8.49 and µ₂ = 7.0116. Based on these calculations, six rats were required per group; one additional rat was added to anticipate possible dropouts, resulting in seven rats per group. Before exposure, the rats were acclimatized for seven days in cages (47 × 33 × 15 cm) at 22 ± 3 °C and 30-70% humidity. MPs exposure was performed in individual chambers (28 × 18 × 12 cm), totaling 21 chambers. After the exposure period, the rats were euthanized with ketamine (5-10 mg/kg body weight), and lung tissues were collected for further analysis.

Determination of dose and duration of exposure

The dose and exposure duration were determined based on OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals No. 412 (28-day subacute inhalation toxicity study)17. The exposure was administered in the form of aerosols sprayed over the entire body of each subject for 6 h per day, 5 days per week, for a total of 28 days. Two exposure doses were used: 1 and 2 mg/L. The control group was not exposed to MPs. Treatment 1 involved exposure to ≤ 10 µm MPs aerosols at a dose of 1 mg/L, whereas Treatment 2 involved exposure to ≤ 10 µm MPs aerosols at a dose of 2 mg/L.

Preparation and characterization of MPs

LDPE microplastics were prepared by mechanically milling LDPE plastic materials using an FCT Z100 miller machine. The use of a milling machine may result in contamination from metal ions, which represents a limitation of the microplastic preparation process in this study. The resulting particles were subsequently sieved through a 1250-mesh sieve to obtain uniform particles with a size of ≤ 10 µm. The selected particle size was based on previous findings reporting that polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) microplastics with diameters ranging from 5.5 to 16.8 µm have been detected in human lung tissue7. Therefore, an intermediate size of 10 µm was selected to represent respirable particles.

The polymer type of the LDPE particles was confirmed using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and particle morphology and size distribution were verified by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Measurement of lairborne MPs levels

The concentration of airborne microplastics (MPs) in the exposure chambers was determined daily using passive sampling. Clean glass collection plates were placed at the center and near the breathing zone of the chamber to capture the settling particles. The chamber walls were rinsed three times with filtered distilled water to recover the adhered MPs. The rinsing liquid was filtered through a 1250-mesh stainless-steel sieve (10 µm) and then passed through a 0.22 µm PTFE membrane filter (90 mm diameter). The retained particles were examined under a binocular microscope (100x magnification) and confirmed as LDPE using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

A limitation of this method is that passive sampling provides only an indirect estimation of airborne MP concentration and does not account for the particle size distribution or dynamic inhalation exposure. Therefore, future studies should incorporate active air sampling techniques to obtain more accurate and representative exposure measurements.

SOD and IsoP expression analysis

The expression of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages was evaluated using immunohistochemistry (IHC). Lung tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 h, followed by dehydration, clearing, paraffin embedding, and sectioning at a thickness of 4-6 µm. The sections were mounted on poly L-lysine-coated glass slides and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining using Mayer’s hematoxylin as a histological reference.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol using anti-SOD-1 (sc-101523; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-F2-isoprostane (Pab ISOPROSTANE [8-ISO-PGF2A]; MyBioSource, Inc.) primary antibodies. After incubation with primary antibodies, the sections were processed using a standard indirect IHC method with a biotin–streptavidin detection system and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the chromogen. Counterstaining was performed using Mayer’s hematoxylin.

Positive and negative controls were included in each batch of staining. The positive control consisted of lung tissue sections known to express SOD and F2-isoprostane, whereas the negative control omitted the primary antibody to ensure specificity. A cell was defined as “positive” when it exhibited brown cytoplasmic staining above a predetermined intensity threshold (optical density > 0.25).

Quantification of SOD and IsoP expression was performed using the ImageJ image analysis software (NIH, USA). The percentage of positively stained alveolar macrophages was calculated by dividing the number of positive cells by the total number of macrophages in each field at 400×. All analyses were conducted in five randomly selected fields per sample to minimize the observer bias.

Data analysis

Data normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity was assessed using Levene’s test. The correlation between airborne microplastic levels and the expression of SOD and IsoP was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation test.177

Results

Types and diameters of microplastic particles

The type of microplastics used in the study was tested using FTIR, as shown in figure 1.

Microplastics (MPs) have recently been recognized as emerging airborne contaminants with potential implications for human health. The extensive use of plastic materials in daily life has led to the release of MPs into both indoor and outdoor air environments. These particles, typically ranging from 0.1 µm to 5 mm in size 1, are generated through the physical, chemical, mechanical, and biological degradation of larger plastic items2. Based on their origin, MPs are classified as primary or secondary, and they appear morphologically as fragments, pellets, fibers, films, or foams3.

Several studies have confirmed the presence of airborne MPs in various areas. In Surabaya, Indonesia, their abundance reached 174.97 particles/m3/day, which was associated with heavy traffic4. In New Jersey, USA, indoor measurements showed high concentrations of polyethylene (PE) fibers, especially in residential areas, indicating that households are major sources of microplastic fibers5. Similar findings in Portugal reported an outdoor abundance of 6 fibers/m3, confirming that microplastics are widespread in the atmosphere6.

Airborne MPs may adversely affect the respiratory system6. Particles smaller than 16.8 µm can penetrate the lower respiratory tract, bypass mucociliary clearance, and accumulate in the alveolar region7. Once deposited, MPs can activate alveolar macrophages, which act as the first line of immune defense through phagocytosis8. This process stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals, potentially leading to oxidative stress and cellular damage9.

To counteract oxidative stress, cells express antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and catalase (CAT)10. However, excessive ROS production can overwhelm the antioxidant defenses, resulting in lipid peroxidation and the formation of biomarkers such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and isoprostanes (IsoP). Elevated levels of these metabolites indicate membrane damage and oxidative imbalance, which may contribute to inflammation and degenerative changes in the lung tissue11.

If oxidative stress leads to phospholipid damage in the cell membrane, it is indicated by the formation of MDA and IsoP as toxic byproducts12. IsoP is a specific product of arachidonic acid peroxidation, which occurs as a result of oxidative stress and cell membrane damage. An increase in IsoP metabolites indicates elevated oxidative stress in the body and may serve as an important biomarker for degenerative diseases13. Inhaled MPs can reach the alveoli and be phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages (AMs). Alveolar macrophages play a crucial role in responding to foreign particles and secreting inflammatory mediators to maintain homeostasis14. MPs trigger inflammatory reactions and oxidative stress, which may alter the expression of molecules associated with these processes, including IsoP. Excessive macrophage activation during inflammatory cell recruitment can lead to inflammation and damage to lung tissue8.

Although several studies have reported the presence and potential toxicity of airborne microplastics, limited research has focused on their specific effects on lung immune cells, particularly the alveolar macrophages. Previous studies have mainly examined oxidative stress markers, such as malondialdehyde (MDA); however, the combined expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and isoprostanes (IsoP) as indicators of oxidative stress and membrane damage in alveolar macrophages has not been investigated. Therefore, this study provides novel insights into the oxidative and inflammatory responses of alveolar macrophages following subacute exposure to low-density polyethylene (LDPE) microplastics. This study aimed to analyze the effects of subacute exposure to low-density polyethylene (LDPE) MPs on oxidative stress and membrane damage in alveolar macrophages of Rattus norvegicus Wistar strain.

Materials and Methods

This study was a true experimental study using a post-test-only control group design. The independent variable was the concentration of airborne MPs, and the dependent variables were SOD and IsoP expression. The study consisted of three groups: control (K), treatment 1 (P1), and treatment 2 (P2) groups.

Research ethics

Ethical approval was obtained for the use of experimental animals. The ethical clearance certificate (No. 1069/EA/KEPK/2023) was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health and Semarang Health Polytechnic.

Experimental animals

Healthy male Rattus norvegicus (Wistar strain) rats weighing 150 ± 20 g were used as the experimental animals. Animals that died during the study were excluded. The sample size was determined using the method described by Lemeshow15 with reference to previous studies. The parameters included the standard deviation of the control group (∑ = 0.53), Z½α = 1.96 (α = 0.05), Zβ = 1.64, and mean responses of µ₁ = 8.49 and µ₂ = 7.0116. Based on these calculations, six rats were required per group; one additional rat was added to anticipate possible dropouts, resulting in seven rats per group. Before exposure, the rats were acclimatized for seven days in cages (47 × 33 × 15 cm) at 22 ± 3 °C and 30-70% humidity. MPs exposure was performed in individual chambers (28 × 18 × 12 cm), totaling 21 chambers. After the exposure period, the rats were euthanized with ketamine (5-10 mg/kg body weight), and lung tissues were collected for further analysis.

Determination of dose and duration of exposure

The dose and exposure duration were determined based on OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals No. 412 (28-day subacute inhalation toxicity study)17. The exposure was administered in the form of aerosols sprayed over the entire body of each subject for 6 h per day, 5 days per week, for a total of 28 days. Two exposure doses were used: 1 and 2 mg/L. The control group was not exposed to MPs. Treatment 1 involved exposure to ≤ 10 µm MPs aerosols at a dose of 1 mg/L, whereas Treatment 2 involved exposure to ≤ 10 µm MPs aerosols at a dose of 2 mg/L.

Preparation and characterization of MPs

LDPE microplastics were prepared by mechanically milling LDPE plastic materials using an FCT Z100 miller machine. The use of a milling machine may result in contamination from metal ions, which represents a limitation of the microplastic preparation process in this study. The resulting particles were subsequently sieved through a 1250-mesh sieve to obtain uniform particles with a size of ≤ 10 µm. The selected particle size was based on previous findings reporting that polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) microplastics with diameters ranging from 5.5 to 16.8 µm have been detected in human lung tissue7. Therefore, an intermediate size of 10 µm was selected to represent respirable particles.

The polymer type of the LDPE particles was confirmed using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and particle morphology and size distribution were verified by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Measurement of lairborne MPs levels

The concentration of airborne microplastics (MPs) in the exposure chambers was determined daily using passive sampling. Clean glass collection plates were placed at the center and near the breathing zone of the chamber to capture the settling particles. The chamber walls were rinsed three times with filtered distilled water to recover the adhered MPs. The rinsing liquid was filtered through a 1250-mesh stainless-steel sieve (10 µm) and then passed through a 0.22 µm PTFE membrane filter (90 mm diameter). The retained particles were examined under a binocular microscope (100x magnification) and confirmed as LDPE using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

A limitation of this method is that passive sampling provides only an indirect estimation of airborne MP concentration and does not account for the particle size distribution or dynamic inhalation exposure. Therefore, future studies should incorporate active air sampling techniques to obtain more accurate and representative exposure measurements.

SOD and IsoP expression analysis

The expression of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages was evaluated using immunohistochemistry (IHC). Lung tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 h, followed by dehydration, clearing, paraffin embedding, and sectioning at a thickness of 4-6 µm. The sections were mounted on poly L-lysine-coated glass slides and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining using Mayer’s hematoxylin as a histological reference.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol using anti-SOD-1 (sc-101523; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-F2-isoprostane (Pab ISOPROSTANE [8-ISO-PGF2A]; MyBioSource, Inc.) primary antibodies. After incubation with primary antibodies, the sections were processed using a standard indirect IHC method with a biotin–streptavidin detection system and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the chromogen. Counterstaining was performed using Mayer’s hematoxylin.

Positive and negative controls were included in each batch of staining. The positive control consisted of lung tissue sections known to express SOD and F2-isoprostane, whereas the negative control omitted the primary antibody to ensure specificity. A cell was defined as “positive” when it exhibited brown cytoplasmic staining above a predetermined intensity threshold (optical density > 0.25).

Quantification of SOD and IsoP expression was performed using the ImageJ image analysis software (NIH, USA). The percentage of positively stained alveolar macrophages was calculated by dividing the number of positive cells by the total number of macrophages in each field at 400×. All analyses were conducted in five randomly selected fields per sample to minimize the observer bias.

Data analysis

Data normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity was assessed using Levene’s test. The correlation between airborne microplastic levels and the expression of SOD and IsoP was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation test.177

Results

Types and diameters of microplastic particles

The type of microplastics used in the study was tested using FTIR, as shown in figure 1.

.JPG)

Figure 1: FTIR spectrum of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) microplastic particles.

The FTIR spectrum shown in figure 1 indicates a strong absorption peak at 2917.76 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the CH₂ functional group. Another peak at 1471.79 cm⁻¹ represents the C-H functional group, and the H-C-H bending vibration appears at 718.76 cm⁻¹. The diameter of the MPs particles was measured using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) at 3300x magnification with a 5 µm scale.

Levels of microplastics in the air

The measurement of MPs levels in chamber air using the passive method is shown in Table 1. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test because the sample size was less than 50, and homogeneity was evaluated using Levene’s test.

The microplastic concentrations in the chamber air for the control group, treatment 1, and treatment 2 are shown in figure 2.

Levels of microplastics in the air

The measurement of MPs levels in chamber air using the passive method is shown in Table 1. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test because the sample size was less than 50, and homogeneity was evaluated using Levene’s test.

The microplastic concentrations in the chamber air for the control group, treatment 1, and treatment 2 are shown in figure 2.

Table 1: Levels of microplastics in chamber air for 28 days

| n | Sample Code | Microplastic Levels (Particles/unit chamber) | Normality test | Homogenity test | ||

| Median (IQR) | Max | Min | ||||

| 7 | K | 3 (2) | 8 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| 7 | P1 | 17 (1.75) | 23 | 12 | ||

| 6 | P2 | 35 (4) | 48 | 27 | ||

Source: Primary data, 2024

.JPG)

Figure 2: airborne microplastics levels of in the exposure chambers.

.JPG)

Figure 2: airborne microplastics levels of in the exposure chambers.

The figure shows the average concentration of MPs particles in the chamber air for each treatment group: control (K), 1 mg/L/day exposure (P1), and 2 mg/L/day exposure (P2). The concentration of airborne MPs increased proportionally with the exposure dose, with the highest level observed in the P2 group. A small number of MPs particles (3.41 particles/unit chamber) were also detected in the control chamber, indicating background contamination.

The concentration of MPs in the chamber air was not normally distributed (p > 0.05) and exhibited nonhomogeneous characteristics. Therefore, a non-parametric analysis using Spearman’s rank correlation was applied to assess the relationship between the administered MP exposure dose and the airborne MP concentration within the chamber.

The concentration of MPs in the chamber air was not normally distributed (p > 0.05) and exhibited nonhomogeneous characteristics. Therefore, a non-parametric analysis using Spearman’s rank correlation was applied to assess the relationship between the administered MP exposure dose and the airborne MP concentration within the chamber.

Tabel 2: Correlation between microplastic exposure dose and airborne microplastic levels in exposure chambers

| Variable | p-value | Spearman’s rho (ρ) |

| MPs Chamber | 0.001 | 0.943 |

Source: Primary data analysis, 2024

A significant and strong positive correlation was observed between the exposure dose and airborne microplastic concentration (ρ = 0.943, p = 0.001), indicating that increasing the administered dose proportionally elevated the MP concentration in the exposure chamber.

SOD and IsoP expression in alveolar macrophages

The expression levels of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages after 28 days of LDPE microplastic exposure are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3, respectively. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity was evaluated using Levene’s test. The results indicated that SOD expression decreased, whereas IsoP expression increased proportionally with the exposure dose. As some data were not normally distributed (p < 0.05), the results are presented as median (interquartile range, IQR) instead of mean ± SD.

The expression levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and isoprostanes (IsoP) in alveolar macrophages after 28 days of microplastic exposure can be seen in figure 3.

A significant and strong positive correlation was observed between the exposure dose and airborne microplastic concentration (ρ = 0.943, p = 0.001), indicating that increasing the administered dose proportionally elevated the MP concentration in the exposure chamber.

SOD and IsoP expression in alveolar macrophages

The expression levels of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages after 28 days of LDPE microplastic exposure are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3, respectively. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity was evaluated using Levene’s test. The results indicated that SOD expression decreased, whereas IsoP expression increased proportionally with the exposure dose. As some data were not normally distributed (p < 0.05), the results are presented as median (interquartile range, IQR) instead of mean ± SD.

The expression levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and isoprostanes (IsoP) in alveolar macrophages after 28 days of microplastic exposure can be seen in figure 3.

Table 3: Expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and isoprostanes (IsoP) in alveolar macrophages after 28 days of microplastic exposure

| N | Group | SOD (cell/field of view) | IsoP (cell/field of view) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) |

Max | Min | Normality/homogenity test |

Median (IQR) | Max | Min | Normality/ homogenity test |

||

| 7 | K | 21 (5) | 33 | 10 | 0.127/0.13 | 1 (2) | 5 | 0 | 0.021/0.014 |

| 7 | P1 | 16.5 (12) | 32 | 5 | 20 (11) | 31 | 5 | ||

| 6 | P2 | 9 (7.75) | 23 | 3 | 22 (26) | 48 | 7 | ||

Source: Primary data, 2025

.JPG) Figure 3: Immunohistochemical expression of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages of Rattus norvegicus after 28 days of exposure to LDPE microplastics.

Figure 3: Immunohistochemical expression of SOD and IsoP in alveolar macrophages of Rattus norvegicus after 28 days of exposure to LDPE microplastics.The mean SOD expression decreased progressively with increasing MPs exposure dose, with the lowest expression observed in the P2 group (2 mg/L/day). In contrast, IsoP expression increased proportionally with the exposure dose, showing the highest intensity in the P2 group. These results indicate an inverse relationship between antioxidant enzyme activity and lipid peroxidation biomarkers following subacute inhalation of LDPE microplastics. Under normal conditions, SOD and IsoP expression were maintained at basal levels in the control group. The visualization of superoxide dismutase and isoprostane expression in the lung tissue of Rattus norvegicus Wistar strain can be seen in figure 4.

Figure 4 shows that alveolar macrophages are located within the alveolar spaces, appearing round or oval in shape and larger than the surrounding cells. Macrophages expressing SOD and IsoP exhibited distinct brown coloration in the cytoplasm, whereas those without SOD and IsoP expression appeared light blue. The brown coloration was not homogeneous because IsoP tended to accumulate in specific cytoplasmic regions that were rich in lipids and had high reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity.

.JPG)

Figure 4: Expression of SOD and IsoP in Alveolar Macrophages of Rattus norvegicus Wistar Strain Lung Tissue.

Figure 4 shows that alveolar macrophages are located within the alveolar spaces, appearing round or oval in shape and larger than the surrounding cells. Macrophages expressing SOD and IsoP exhibited distinct brown coloration in the cytoplasm, whereas those without SOD and IsoP expression appeared light blue. The brown coloration was not homogeneous because IsoP tended to accumulate in specific cytoplasmic regions that were rich in lipids and had high reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity.

.JPG)

Figure 4: Expression of SOD and IsoP in Alveolar Macrophages of Rattus norvegicus Wistar Strain Lung Tissue.

The effect of subacute exposure to LDPE microplastics on SOD and IsoP expression in alveolar macrophages

The non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation test was performed because the data did not meet the normality assumption (Table 4).

The non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation test was performed because the data did not meet the normality assumption (Table 4).

Table 4: Results of the effect of subacute exposure to LDPE microplastics on SOD and IsoP expression in alveolar macrophages

| Variable | p-value | Spearman’s rho (ρ) |

| SOD | 0.009* | -0.566 |

| F2 Isoprostane | 0.001* | 0.742 |

Source: primary data analysis, 2025

As shown in Table 4, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis demonstrated a significant relationship between airborne LDPE microplastic levels and the expression of oxidative stress markers in alveolar macrophages (p < 0.05). A moderate negative correlation was observed between microplastic levels and SOD expression (ρ = -0.566, p = 0.009), indicating that higher MPs concentrations were associated with reduced antioxidant enzyme activity. Conversely, a strong positive correlation was found between microplastic levels and F2-Isoprostane expression (ρ = 0.742, p = 0.001), suggesting increased lipid peroxidation with higher MPs exposure. These findings indicate that elevated MPs exposure may disrupt the oxidative balance in alveolar macrophages, leading to reduced antioxidant defense and enhanced oxidative damage.

Discussions

The results of SEM Scanning electron microscopy revealed that the microplastics used for animal exposure had a diameter of less than 5 µm. The size of microplastic particles influences their toxicity, with smaller particles exhibiting a greater potential for toxic effects18. The surfaces of the microplastic particles were irregular, and their shapes determined the biological responses in the tissue. Particles with irregular, sharp, and rigid edges can induce biological effects through inflammatory mechanisms, leading to blood vessel dilation and facilitating leukocyte phagocytosis. However, microplastic particles cannot be fully degraded by phagocytes. Attempts to eliminate microplastics may occur via oxygen-dependent oxidative mechanisms or independently of inflammatory mediators. These responses can subsequently damage the surrounding cells19.

The diameter of microplastic particles capable of entering the respiratory system ranges from 0.1 to 10 µm20. In outdoor air, microplastics such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS) have been detected in the form of fibers, fragments, foam, and films, with concentrations ranging from 175 to 313 particles/m²/day in Dongguan, China21. Microplastics have also been reported as indoor-air pollutants. In Surabaya, Indonesia, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) microplastics, poly (cis/trans-cyclohexanediol terephthalate), and viscose rayon were detected at a concentration of 3.82 particles/m³ in office air22. The highest concentration of microplastics in household air was reported to be 6.169 particles/m²/day. The quantity of microplastics in indoor air is influenced by factors such as ventilation, presence of solid waste, use of plastic furniture, and the activities of room occupants22-25.

If not properly addressed, the presence of microplastics in the air can negatively impact human health, particularly lung tissue. Polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) microplastics have been detected in human lung tissue, with 33 particles measuring less than 5.5 µm and four fibrous particles ranging from 8.12 to 16.8 µm in size7. These findings indicate that microplastics can bypass the physical defense mechanisms of the respiratory tract, leading to their accumulation in the alveoli8. Inhaled microplastics may be cleared through mechanical processes such as sneezing, mucociliary transport, phagocytosis by macrophages, and lymphatic transport26. However, not all microplastics in lung tissue are removed by these mechanisms. Residual microplastics can induce inflammation by releasing intracellular mediators, proteases, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Microplastics can persist in lung tissue fluid for up to 180 days without significant changes in surface area, potentially resulting in fibrosis and, in some cases, cancer27.

The present study demonstrated that subacute exposure to airborne LDPE microplastics significantly affects oxidative stress markers in alveolar macrophages. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis revealed a moderate negative correlation between LDPE microplastic levels and SOD expression (ρ = -0.566, p = 0.009), while a strong positive correlation was observed with IsoP expression (ρ = 0.742, p = 0.001). These results suggest that increased exposure to LDPE microplastics reduces antioxidant defense and enhances lipid peroxidation, indicating an imbalance in the oxidative homeostasis.

These findings align with those of previous studies demonstrating that microplastics can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induce oxidative stress in pulmonary cells28, 29. Specifically, decreased SOD activity has been reported in alveolar macrophages exposed to polystyrene and polyethylene microplastics, reflecting an impaired enzymatic defense against ROS. Meanwhile, the elevation of IsoP levels corroborates enhanced lipid peroxidation as a result of oxidative injury, consistent with the oxidative stress mechanisms described in inhalation toxicology30.

Interestingly, our results partially contrast with those of Lestari et al. (2025)31, who reported no significant change in SOD activity following subacute polyethylene exposure. This discrepancy may be due to differences in particle size, exposure duration, and experimental models. Our study employed repeated subacute exposure, which may better mimic chronic environmental inhalation. These differences highlight the importance of considering exposure and particle characteristics when evaluating microplastic toxicity.

Consistent with previous findings, exposure to polystyrene microplastics (0.01 mg/kg for four weeks) in Rattus norvegicus Wistar strain has been shown to significantly decrease CAT, SOD, and GPx activity while elevating ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, indicating an oxidative imbalance32. Similarly, exposure to polypropylene (PP) microplastics via inhalation (2 mg/m³) induces persistent pulmonary inflammation and histopathological alterations in lung tissue33.Klik atau ketuk di sini untuk memasukkan teks. Microplastics (MPs) induce inflammation via the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway, promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Polystyrene MPs (PS-MPs) also cause cytotoxicity and oxidative stress, increasing ROS, MDA, and liver enzyme levels, while reducing antioxidant defenses (SOD and GSH). These effects disrupt cellular homeostasis, leading to lipid accumulation, fibrosis, and steatosis, ultimately aggravating disease progression34. Conversely, another study involving low-density polyethylene (LDPE) microplastics (< 10 µm, 1–5 mg/L aerosol exposure) in Rattus norvegicus reported no significant changes in SOD or CAT expression at different exposure concentrations. These discrepancies may be attributed to variations in the microplastic dose, exposure method, and environmental conditions employed across experimental designs31.

Oxidative stress damages cellular components, including the lipids in cell membranes. IsoPs are byproducts of lipid peroxidation resulting from the oxidation of arachidonic acid. The expression of IsoP in alveolar macrophages indicates that microplastic exposure increases lipid peroxidation, contributing to cellular damage35. This is consistent with previous research in which Rattus norvegicus (Wistar strain) were orally exposed to LDPE microplastics measuring ≤20 µm in size. Five different microplastic doses were administered over 90 days. The study reported that higher microplastic levels in the blood corresponded to an increased expression of malondialdehyde (MDA) in hippocampal neurons36. IsoP and MDA are byproducts of lipid peroxidation induced by free radicals. IsoP is formed non-enzymatically, whereas MDA is formed by the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids. IsoP is considered a more sensitive and expressive indicator of ROS-induced lipid peroxidation13, 37. Persistent oxidative stress can lead to cellular damage and chronic inflammation, ultimately compromising lung tissue integrity.

Overall, these results underscore that even subacute exposure to LDPE microplastics can disrupt the oxidative balance in alveolar macrophages, potentially compromising pulmonary antioxidant defense and increasing susceptibility to oxidative damage. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence linking airborne microplastics with respiratory oxidative stress and support the need for further research on long-term pulmonary effects.

Although the exposure concentration applied in this study exceeded typical environmental levels, the identified mechanistic pathways are relevant for understanding chronic or occupational exposure scenarios, particularly in the plastic manufacturing and recycling industries. These findings provide novel insights into the oxidative and inflammatory processes induced by LDPE microplastics, emphasizing the importance of further investigations to establish safe exposure thresholds and evaluate long-term respiratory risks in humans.

Conclusions

Exposure to polyethylene (LDPE) microplastics smaller than 5 µm induces oxidative stress in lung tissue, as evidenced by elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, altered antioxidant enzyme SOD expression, and increased lipid peroxidation products such as F2-isoprostanes. The particle size and morphology play critical roles in inflammatory responses and alveolar accumulation. Although the experimental doses exceeded typical environmental exposure, the identified cellular mechanisms highlight the potential risks associated with chronic or high-level exposure, such as in occupational settings. This study provides novel insights into the link between microplastic characteristics, oxidative damage, and lung tissue impairment, emphasizing the need for further investigation of safe exposure thresholds in humans.

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted independently

by the authors without financial support from grants or other funding sources. The authors sincerely acknowledge the contributions of all individuals who assisted with the research and preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

According to the authors, this study was conducted without any financial or commercial relationships that could give rise to potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received no external funding.

Ethical considerations

The authors declare that this manuscript contains no fabrication, falsification, plagiarism, duplication, fragmentation or infringement of data or copyright. Furthermore, this work has not been presented at any scientific meetings or published elsewhere in any form.

Code of Ethics

Ethical approval for the use of experimental animals was obtained prior to the commencement of the study. The ethical clearance certificate (No. 1069/EA/KEPK/2023) was issued by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health in collaboration with Semarang Health Polytechnic

Authors’ Contributions

Four authors contributed to the research and manuscript preparations. Tri Marthy Mulyasari served as the lead researcher, overseeing data collection and analysis. Jojok Mukono contributed as a research consultant during the study. I

Ketut Sudiana was responsible for the immunohistochemical analyses and also served as a research consultant. Prehatin Trirahayu Ningrum contributed to the data analysis.

This is an Open-Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work for commercial use.

References

1. World Health Organization. Microplastics in drinking-water. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019.

2. Jain S, Mishra D, Khare P. Microplastics as an Emerging Contaminant in Environment: Occurrence, Distribution, and Management Strategy. Management of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CEC) in Environment.Elsevier Inc.; 2021: 281-99.

3. Kershaw PJ, Turra A, Galgani F. Guidelines For the Monitoring and Assessment of Plastic Litter and microplastics in the ocean. 2019.

4. Syafei AD, Nurasrin NR, Assomadi AF, et al. Microplastic pollution in the ambient air of Surabaya, Indonesia. Curr World Environ. 2019;14(2):290-8.

5. Yao Y, Glamoclija M, Murphy A, et al. Characterization of microplastics in indoor and ambient air in northern New Jersey. Environ Res. 2022;207:112142.

6. Prata JC, Castro JL, da Costa JP, et al. The importance of contamination control in airborne fibers and microplastic sampling: experiences from indoor and outdoor air sampling in Aveiro, Portugal. Mar Pollut Bull. 2020;159:111522.

7. Amato-Lourenço LF, Carvalho-Oliveira R, Júnior GR, et al. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J Hazard Mater . 2021; 416:126124.

8. Azhary M, Yunus F, Diah Handayani RR, et al. Mekanisme Pertahanan Saluran Nafas. Kedokteran Nanggroe Medika. 2022;5(1):24-33.

9. Mulianto N. Malondialdehid sebagai penanda stres oksidatif pada berbagai penyakit kulit. Cermin Dunia Kedokteran. 2020;47(1):39-44.

10. Simanjuntak E, Zulham. Superoksida Dismutase (SOD) dan radikal bebas. Jurnal Keperawatan dan Fisioterapi (JKF). 2020;2(2): 124-9.

11. Wahjuni S. Superoksida Dismutase (SOD) sebagai prekusor antioksidan endogen pada stress oksidatif. Denpasar: Udayana University Press; 2015.

12. Braun H, Hauke M, Eckenstaler R, et al. The F2-isoprostane 8-iso-PGF2α attenuates atherosclerotic lesion formation in Ldlr-deficient mice – Potential role of vascular thromboxane A2 receptors: 8-iso-PGF2α reduces atherosclerosis in Ldlr-deficient mice. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2022;185:36-45.

13. Thatcher TH, Peters-Golden M. From biomarker to mechanism? F2-isoprostanes in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(5):530-2.

14. Hirayama D, Iida T, Nakase H. The phagocytic function of macrophage-enforcing innate immunity and tissue homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;19(1):92.

15. Lemeshow S, Klar J, Lwanga sK, et al. Besar sampel dalam penelitian kesehatan. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press; 1997:2528-0929.

16. Wibowo S, Lestari ES, Arifin MT, et al. Clove flower extracts (Syzgium aromaticum) increased incision wound epithelization, platelet count, and TGF-β levels in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-infected rats. Jurnal Kedokteran dan Kesehatan Indonesia. 2023;14(3):248-55.

17. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [Internet]. OECD/OCDE 412 OECD GUIDELINES ON THE TESTING OF CHEMICALS 28-day (subacute) inhalation toxicity study. 2018. Available from: https:// www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/ oecd/en/publications/reports/2018/07/ guidance- document-on-inhalation-toxicity-studies- second-edition_8d0ac4ff/fba59116-en.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwi9y43bgt2RAxVc9QIHHb7OHhEQFnoECB4QAQ&usg=AOvVaw0aSVV21m7bpSs2x0sKr6aU. [cited Des 20, 2018].

18. Pelegrini K, Pereira TCB, Maraschin TG, et al. Micro- and nanoplastic toxicity: a review on size, type, source, and test-organism implications. Sci Total Environ. 2023;878: 162954.

19. Hwang J, Choi D, Han S, et al. An assessment of the toxicity of polypropylene microplastics in human derived cells. Sci Total Environ. 2019;684:657-69.

20. Dong CD, Chen CW, Chen YC, et al. Polystyrene microplastic particles: In vitro pulmonary toxicity assessment. J Hazard Mater .2020; 385:121575.

21. Cai L, Wang J, Peng J, et al. Characteristic of microplastics in the atmospheric fallout from Dongguan city, China: preliminary research and first evidence. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24(32):24928-35.

22. Bahrina I. Korelasi Aktivitas Karyawan dan Mikroplastik di Udara (Studi Kasus: Dalam Sebuah Gedung Perkantoran Pemerintah di Surabaya) (Doctoral dissertation, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember). 2021.

23. Dris R, Gasperi J, Mirande C, et al. A first overview of textile fibers, including microplastics, in indoor and outdoor environments. Environmental Pollution. 2017;221:453-8.

24. Soltani NS, Taylor MP, Wilson SP. Quantification and exposure assessment of microplastics in Australian indoor house dust. Environmental Pollution. 2021;283:117064.

25. Xie Y, Li Y, Feng Y, et al. Inhalable microplastics prevails in air: exploring the size detection limit. Environ Int. 2022;162:107151.

26. Prata JC. Airborne microplastics: consequences to human health?. Environmental Pollution. 2018;234:115-26.

27. Gasperi J, Wright SL, Dris R, et al. Microplastics in air : are we breathing it in ? Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 2018;1:1-5.

28. Li X, Zhang T, Lv W, et al. Intratracheal administration of polystyrene microplastics induces pulmonary fibrosis by activating oxidative stress and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022; 232:113238.

29. Zou H, Qu H, Bian Y, et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce oxidative stress in mouse hepatocytes in relation to their size. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8): 7382.

30. Zhang X, Zhu H, Zhang J. Oxidative stress on the ground and in the microgravity environment : pathophysiological effects and treatment. Antioxidant. 2025; 14(2):231.

31. Lestari KS, Sincihu Y, Latif MT, et al. No Prominent SOD and CAT Lung Expression of Rats Due to Exposure to Low-Density Polyethylene in The Air. 2025;7:2125-37.

32. Faisal Hayat M, Ur Rahman A, Tahir A, et al. Palliative potential of robinetin to avert polystyrene microplastics instigated pulmonary toxicity in rats. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2024;36(9):103348.

33. Tomonaga T, Higashi H, Izumi H, et al. Investigation of pulmonary inflammatory responses following intratracheal instillation of and inhalation exposure to polypropylene microplastics. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2024;21(1):29.

34. Rahimi NR, Dehghani M, Fouladi-Fard R. Impact of micro and nanoplastics on inflammatory and antioxidant gene expression in the gastrointestinal system. Journal of Environmental Health and Sustainable Development. 2025;10(1):2483-6.

35. Suzuki T, Kropski J, Chen J, et al. The F2-Isoprostane:Thromboxane-prostanoid receptor signaling axis drives persistent fibroblast activation in pulmonary fibrosis. 2021. p. 1-25.

36. Sincihu Y, Lusno MFD, Mulyasari TM, et al. Wistar rats hippocampal neurons response to blood low-density polyethylene microplastics: a pathway analysis of SOD, CAT, MDA, 8-OHdG expression in hippocampal neurons and blood serum Aβ42 levels. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2023:73-83.

37. Rifka Y, Rasfayanah, Arfah AI, et al. Efekivitas Madu terhadap Kadar Malondialdehyde (MDA) Plasma sebagai Penanda Stress Oksidatif Pada Kondisi Hyperglikemi. Fakumi Medical Journal: Jurnal Mahasiswa Kedokteran. 2021;1(2):137-43.

As shown in Table 4, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis demonstrated a significant relationship between airborne LDPE microplastic levels and the expression of oxidative stress markers in alveolar macrophages (p < 0.05). A moderate negative correlation was observed between microplastic levels and SOD expression (ρ = -0.566, p = 0.009), indicating that higher MPs concentrations were associated with reduced antioxidant enzyme activity. Conversely, a strong positive correlation was found between microplastic levels and F2-Isoprostane expression (ρ = 0.742, p = 0.001), suggesting increased lipid peroxidation with higher MPs exposure. These findings indicate that elevated MPs exposure may disrupt the oxidative balance in alveolar macrophages, leading to reduced antioxidant defense and enhanced oxidative damage.

Discussions

The results of SEM Scanning electron microscopy revealed that the microplastics used for animal exposure had a diameter of less than 5 µm. The size of microplastic particles influences their toxicity, with smaller particles exhibiting a greater potential for toxic effects18. The surfaces of the microplastic particles were irregular, and their shapes determined the biological responses in the tissue. Particles with irregular, sharp, and rigid edges can induce biological effects through inflammatory mechanisms, leading to blood vessel dilation and facilitating leukocyte phagocytosis. However, microplastic particles cannot be fully degraded by phagocytes. Attempts to eliminate microplastics may occur via oxygen-dependent oxidative mechanisms or independently of inflammatory mediators. These responses can subsequently damage the surrounding cells19.

The diameter of microplastic particles capable of entering the respiratory system ranges from 0.1 to 10 µm20. In outdoor air, microplastics such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS) have been detected in the form of fibers, fragments, foam, and films, with concentrations ranging from 175 to 313 particles/m²/day in Dongguan, China21. Microplastics have also been reported as indoor-air pollutants. In Surabaya, Indonesia, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) microplastics, poly (cis/trans-cyclohexanediol terephthalate), and viscose rayon were detected at a concentration of 3.82 particles/m³ in office air22. The highest concentration of microplastics in household air was reported to be 6.169 particles/m²/day. The quantity of microplastics in indoor air is influenced by factors such as ventilation, presence of solid waste, use of plastic furniture, and the activities of room occupants22-25.

If not properly addressed, the presence of microplastics in the air can negatively impact human health, particularly lung tissue. Polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) microplastics have been detected in human lung tissue, with 33 particles measuring less than 5.5 µm and four fibrous particles ranging from 8.12 to 16.8 µm in size7. These findings indicate that microplastics can bypass the physical defense mechanisms of the respiratory tract, leading to their accumulation in the alveoli8. Inhaled microplastics may be cleared through mechanical processes such as sneezing, mucociliary transport, phagocytosis by macrophages, and lymphatic transport26. However, not all microplastics in lung tissue are removed by these mechanisms. Residual microplastics can induce inflammation by releasing intracellular mediators, proteases, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Microplastics can persist in lung tissue fluid for up to 180 days without significant changes in surface area, potentially resulting in fibrosis and, in some cases, cancer27.

The present study demonstrated that subacute exposure to airborne LDPE microplastics significantly affects oxidative stress markers in alveolar macrophages. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis revealed a moderate negative correlation between LDPE microplastic levels and SOD expression (ρ = -0.566, p = 0.009), while a strong positive correlation was observed with IsoP expression (ρ = 0.742, p = 0.001). These results suggest that increased exposure to LDPE microplastics reduces antioxidant defense and enhances lipid peroxidation, indicating an imbalance in the oxidative homeostasis.

These findings align with those of previous studies demonstrating that microplastics can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induce oxidative stress in pulmonary cells28, 29. Specifically, decreased SOD activity has been reported in alveolar macrophages exposed to polystyrene and polyethylene microplastics, reflecting an impaired enzymatic defense against ROS. Meanwhile, the elevation of IsoP levels corroborates enhanced lipid peroxidation as a result of oxidative injury, consistent with the oxidative stress mechanisms described in inhalation toxicology30.

Interestingly, our results partially contrast with those of Lestari et al. (2025)31, who reported no significant change in SOD activity following subacute polyethylene exposure. This discrepancy may be due to differences in particle size, exposure duration, and experimental models. Our study employed repeated subacute exposure, which may better mimic chronic environmental inhalation. These differences highlight the importance of considering exposure and particle characteristics when evaluating microplastic toxicity.

Consistent with previous findings, exposure to polystyrene microplastics (0.01 mg/kg for four weeks) in Rattus norvegicus Wistar strain has been shown to significantly decrease CAT, SOD, and GPx activity while elevating ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, indicating an oxidative imbalance32. Similarly, exposure to polypropylene (PP) microplastics via inhalation (2 mg/m³) induces persistent pulmonary inflammation and histopathological alterations in lung tissue33.

Oxidative stress damages cellular components, including the lipids in cell membranes. IsoPs are byproducts of lipid peroxidation resulting from the oxidation of arachidonic acid. The expression of IsoP in alveolar macrophages indicates that microplastic exposure increases lipid peroxidation, contributing to cellular damage35. This is consistent with previous research in which Rattus norvegicus (Wistar strain) were orally exposed to LDPE microplastics measuring ≤20 µm in size. Five different microplastic doses were administered over 90 days. The study reported that higher microplastic levels in the blood corresponded to an increased expression of malondialdehyde (MDA) in hippocampal neurons36. IsoP and MDA are byproducts of lipid peroxidation induced by free radicals. IsoP is formed non-enzymatically, whereas MDA is formed by the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids. IsoP is considered a more sensitive and expressive indicator of ROS-induced lipid peroxidation13, 37. Persistent oxidative stress can lead to cellular damage and chronic inflammation, ultimately compromising lung tissue integrity.

Overall, these results underscore that even subacute exposure to LDPE microplastics can disrupt the oxidative balance in alveolar macrophages, potentially compromising pulmonary antioxidant defense and increasing susceptibility to oxidative damage. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence linking airborne microplastics with respiratory oxidative stress and support the need for further research on long-term pulmonary effects.

Although the exposure concentration applied in this study exceeded typical environmental levels, the identified mechanistic pathways are relevant for understanding chronic or occupational exposure scenarios, particularly in the plastic manufacturing and recycling industries. These findings provide novel insights into the oxidative and inflammatory processes induced by LDPE microplastics, emphasizing the importance of further investigations to establish safe exposure thresholds and evaluate long-term respiratory risks in humans.

Conclusions

Exposure to polyethylene (LDPE) microplastics smaller than 5 µm induces oxidative stress in lung tissue, as evidenced by elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, altered antioxidant enzyme SOD expression, and increased lipid peroxidation products such as F2-isoprostanes. The particle size and morphology play critical roles in inflammatory responses and alveolar accumulation. Although the experimental doses exceeded typical environmental exposure, the identified cellular mechanisms highlight the potential risks associated with chronic or high-level exposure, such as in occupational settings. This study provides novel insights into the link between microplastic characteristics, oxidative damage, and lung tissue impairment, emphasizing the need for further investigation of safe exposure thresholds in humans.

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted independently

by the authors without financial support from grants or other funding sources. The authors sincerely acknowledge the contributions of all individuals who assisted with the research and preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

According to the authors, this study was conducted without any financial or commercial relationships that could give rise to potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received no external funding.

Ethical considerations

The authors declare that this manuscript contains no fabrication, falsification, plagiarism, duplication, fragmentation or infringement of data or copyright. Furthermore, this work has not been presented at any scientific meetings or published elsewhere in any form.

Code of Ethics

Ethical approval for the use of experimental animals was obtained prior to the commencement of the study. The ethical clearance certificate (No. 1069/EA/KEPK/2023) was issued by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health in collaboration with Semarang Health Polytechnic

Authors’ Contributions

Four authors contributed to the research and manuscript preparations. Tri Marthy Mulyasari served as the lead researcher, overseeing data collection and analysis. Jojok Mukono contributed as a research consultant during the study. I

Ketut Sudiana was responsible for the immunohistochemical analyses and also served as a research consultant. Prehatin Trirahayu Ningrum contributed to the data analysis.

This is an Open-Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work for commercial use.

References

1. World Health Organization. Microplastics in drinking-water. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019.

2. Jain S, Mishra D, Khare P. Microplastics as an Emerging Contaminant in Environment: Occurrence, Distribution, and Management Strategy. Management of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CEC) in Environment.Elsevier Inc.; 2021: 281-99.

3. Kershaw PJ, Turra A, Galgani F. Guidelines For the Monitoring and Assessment of Plastic Litter and microplastics in the ocean. 2019.

4. Syafei AD, Nurasrin NR, Assomadi AF, et al. Microplastic pollution in the ambient air of Surabaya, Indonesia. Curr World Environ. 2019;14(2):290-8.

5. Yao Y, Glamoclija M, Murphy A, et al. Characterization of microplastics in indoor and ambient air in northern New Jersey. Environ Res. 2022;207:112142.

6. Prata JC, Castro JL, da Costa JP, et al. The importance of contamination control in airborne fibers and microplastic sampling: experiences from indoor and outdoor air sampling in Aveiro, Portugal. Mar Pollut Bull. 2020;159:111522.

7. Amato-Lourenço LF, Carvalho-Oliveira R, Júnior GR, et al. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J Hazard Mater . 2021; 416:126124.

8. Azhary M, Yunus F, Diah Handayani RR, et al. Mekanisme Pertahanan Saluran Nafas. Kedokteran Nanggroe Medika. 2022;5(1):24-33.

9. Mulianto N. Malondialdehid sebagai penanda stres oksidatif pada berbagai penyakit kulit. Cermin Dunia Kedokteran. 2020;47(1):39-44.

10. Simanjuntak E, Zulham. Superoksida Dismutase (SOD) dan radikal bebas. Jurnal Keperawatan dan Fisioterapi (JKF). 2020;2(2): 124-9.

11. Wahjuni S. Superoksida Dismutase (SOD) sebagai prekusor antioksidan endogen pada stress oksidatif. Denpasar: Udayana University Press; 2015.

12. Braun H, Hauke M, Eckenstaler R, et al. The F2-isoprostane 8-iso-PGF2α attenuates atherosclerotic lesion formation in Ldlr-deficient mice – Potential role of vascular thromboxane A2 receptors: 8-iso-PGF2α reduces atherosclerosis in Ldlr-deficient mice. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2022;185:36-45.

13. Thatcher TH, Peters-Golden M. From biomarker to mechanism? F2-isoprostanes in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(5):530-2.

14. Hirayama D, Iida T, Nakase H. The phagocytic function of macrophage-enforcing innate immunity and tissue homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;19(1):92.

15. Lemeshow S, Klar J, Lwanga sK, et al. Besar sampel dalam penelitian kesehatan. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press; 1997:2528-0929.

16. Wibowo S, Lestari ES, Arifin MT, et al. Clove flower extracts (Syzgium aromaticum) increased incision wound epithelization, platelet count, and TGF-β levels in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-infected rats. Jurnal Kedokteran dan Kesehatan Indonesia. 2023;14(3):248-55.

17. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [Internet]. OECD/OCDE 412 OECD GUIDELINES ON THE TESTING OF CHEMICALS 28-day (subacute) inhalation toxicity study. 2018. Available from: https:// www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/ oecd/en/publications/reports/2018/07/ guidance- document-on-inhalation-toxicity-studies- second-edition_8d0ac4ff/fba59116-en.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwi9y43bgt2RAxVc9QIHHb7OHhEQFnoECB4QAQ&usg=AOvVaw0aSVV21m7bpSs2x0sKr6aU. [cited Des 20, 2018].

18. Pelegrini K, Pereira TCB, Maraschin TG, et al. Micro- and nanoplastic toxicity: a review on size, type, source, and test-organism implications. Sci Total Environ. 2023;878: 162954.

19. Hwang J, Choi D, Han S, et al. An assessment of the toxicity of polypropylene microplastics in human derived cells. Sci Total Environ. 2019;684:657-69.

20. Dong CD, Chen CW, Chen YC, et al. Polystyrene microplastic particles: In vitro pulmonary toxicity assessment. J Hazard Mater .2020; 385:121575.

21. Cai L, Wang J, Peng J, et al. Characteristic of microplastics in the atmospheric fallout from Dongguan city, China: preliminary research and first evidence. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24(32):24928-35.

22. Bahrina I. Korelasi Aktivitas Karyawan dan Mikroplastik di Udara (Studi Kasus: Dalam Sebuah Gedung Perkantoran Pemerintah di Surabaya) (Doctoral dissertation, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember). 2021.

23. Dris R, Gasperi J, Mirande C, et al. A first overview of textile fibers, including microplastics, in indoor and outdoor environments. Environmental Pollution. 2017;221:453-8.

24. Soltani NS, Taylor MP, Wilson SP. Quantification and exposure assessment of microplastics in Australian indoor house dust. Environmental Pollution. 2021;283:117064.

25. Xie Y, Li Y, Feng Y, et al. Inhalable microplastics prevails in air: exploring the size detection limit. Environ Int. 2022;162:107151.

26. Prata JC. Airborne microplastics: consequences to human health?. Environmental Pollution. 2018;234:115-26.

27. Gasperi J, Wright SL, Dris R, et al. Microplastics in air : are we breathing it in ? Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 2018;1:1-5.

28. Li X, Zhang T, Lv W, et al. Intratracheal administration of polystyrene microplastics induces pulmonary fibrosis by activating oxidative stress and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022; 232:113238.

29. Zou H, Qu H, Bian Y, et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce oxidative stress in mouse hepatocytes in relation to their size. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8): 7382.

30. Zhang X, Zhu H, Zhang J. Oxidative stress on the ground and in the microgravity environment : pathophysiological effects and treatment. Antioxidant. 2025; 14(2):231.

31. Lestari KS, Sincihu Y, Latif MT, et al. No Prominent SOD and CAT Lung Expression of Rats Due to Exposure to Low-Density Polyethylene in The Air. 2025;7:2125-37.

32. Faisal Hayat M, Ur Rahman A, Tahir A, et al. Palliative potential of robinetin to avert polystyrene microplastics instigated pulmonary toxicity in rats. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2024;36(9):103348.

33. Tomonaga T, Higashi H, Izumi H, et al. Investigation of pulmonary inflammatory responses following intratracheal instillation of and inhalation exposure to polypropylene microplastics. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2024;21(1):29.

34. Rahimi NR, Dehghani M, Fouladi-Fard R. Impact of micro and nanoplastics on inflammatory and antioxidant gene expression in the gastrointestinal system. Journal of Environmental Health and Sustainable Development. 2025;10(1):2483-6.

35. Suzuki T, Kropski J, Chen J, et al. The F2-Isoprostane:Thromboxane-prostanoid receptor signaling axis drives persistent fibroblast activation in pulmonary fibrosis. 2021. p. 1-25.

36. Sincihu Y, Lusno MFD, Mulyasari TM, et al. Wistar rats hippocampal neurons response to blood low-density polyethylene microplastics: a pathway analysis of SOD, CAT, MDA, 8-OHdG expression in hippocampal neurons and blood serum Aβ42 levels. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2023:73-83.

37. Rifka Y, Rasfayanah, Arfah AI, et al. Efekivitas Madu terhadap Kadar Malondialdehyde (MDA) Plasma sebagai Penanda Stress Oksidatif Pada Kondisi Hyperglikemi. Fakumi Medical Journal: Jurnal Mahasiswa Kedokteran. 2021;1(2):137-43.

Type of Study: Original articles |

Subject:

Environmental toxicology

Received: 2025/08/13 | Accepted: 2025/10/20 | Published: 2025/12/25

Received: 2025/08/13 | Accepted: 2025/10/20 | Published: 2025/12/25

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |