Volume 10, Issue 4 (December 2025)

J Environ Health Sustain Dev 2025, 10(4): 2804-2814 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mazloomian M, Ghaneian M T, Borhani Yazdi N, Ehrampoush M H, Madadizadeh F, Gholami M. Dental Amalgam-Derived Mercury in Wastewater: A Systematic Review of Environmental and Health Impacts, and Control Strategies. J Environ Health Sustain Dev 2025; 10 (4) :2804-2814

URL: http://jehsd.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1049-en.html

URL: http://jehsd.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1049-en.html

Mahla Mazloomian

, Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian

, Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian

, Niloufar Borhani Yazdi

, Niloufar Borhani Yazdi

, Mohammad Hassan Ehrampoush

, Mohammad Hassan Ehrampoush

, Farzan Madadizadeh

, Farzan Madadizadeh

, Maryam Gholami *

, Maryam Gholami *

, Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian

, Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian

, Niloufar Borhani Yazdi

, Niloufar Borhani Yazdi

, Mohammad Hassan Ehrampoush

, Mohammad Hassan Ehrampoush

, Farzan Madadizadeh

, Farzan Madadizadeh

, Maryam Gholami *

, Maryam Gholami *

Genetics and Environmental Hazards Research Center, Abarkouh School of Medical Sciences, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran & Environmental Sciences and Technology Research Center, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

Keywords: Dental Amalgam, Mercury, Dental Unit Wastewater, Amalgam Separator, Environmental Pollution, Wastewater Management.

Full-Text [PDF 563 kb]

(38 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (136 Views)

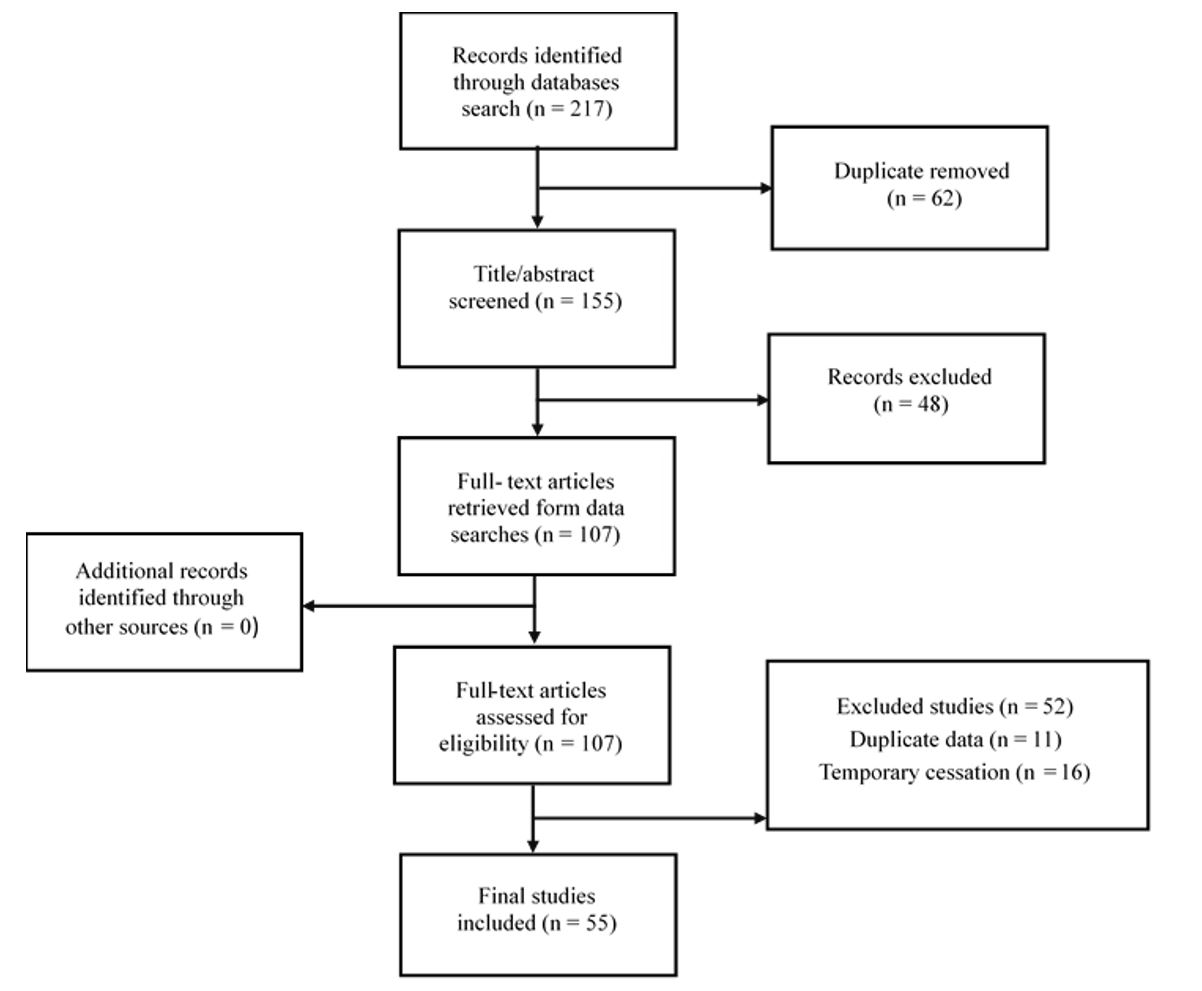

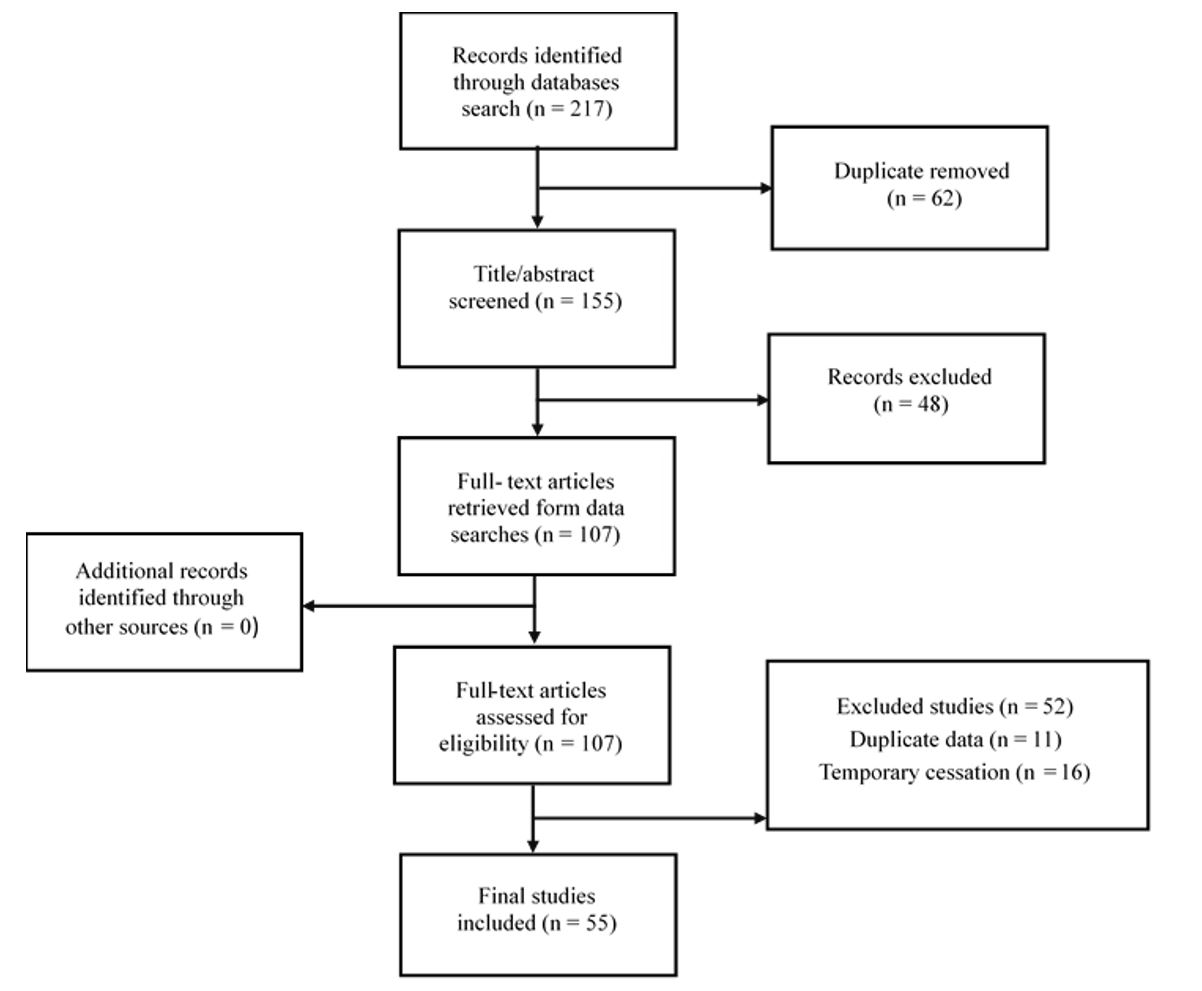

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of study selection.

Mercury toxicity and health implications

Mercury is a potent heavy metal, and its toxicity is dependent on its chemical form (elemental (Hg⁰), inorganic (Hg²⁺), or organic (notably methylmercury (MeHg))) and its route of exposure 21. Elemental mercury vapor, common in occupational settings such as dentistry and mining, primarily affects the nervous and respiratory systems 21. Although inorganic mercury is less readily absorbed, it can cause nephrotoxicity, gastrointestinal symptoms, and systemic toxicity at high doses. MeHg often acquired through contaminated fish, MeHg readily crosses the placental and blood-brain barriers. Prenatal exposure is associated with persistent neurodevelopmental impairments, including cognitive, motor, and language deficits. In adults, it can disrupt sensory processing, motor coordination, and executive function 22-24. At the molecular level, mercury's high affinity for sulfhydryl groups disrupts protein function and enzyme activity, inducing oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation, which lead to neuronal and renal damage. Epigenetic modifications may mediate long-term neurobehavioral outcomes. Inorganic mercury can be methylated in aquatic systems by anaerobic microbes; the resulting MeHg bioaccumulates and biomagnifies in the food web, posing significant risks to ecosystems and human health 25-27. Even at lower doses, mercury exposure can cause irritability, social withdrawal, tremors, sensory alterations, and memory impairments 10, 28.

Regulatory framework and management strategies

In response to these documented risks, regulatory bodies have established strict limits. The U.S. EPA has set a maximum permissible dose for mercury in wastewater at 0.1 mg/L and classifies amalgam waste as special waste 4, 29. A pivotal regulatory action was the 2017 EPA final rule requiring dental offices to install amalgam separators, with a compliance deadline of July 14, 2020 5, 30. A multifaceted approach to mitigate mercury release from dentistry has been proposed and implemented, as outlined in Table 2 31-34.

Full-Text: (17 Views)

Dental Amalgam-Derived Mercury in Wastewater: A Systematic Review of Environmental and Health Impacts, and Control Strategies

Mahla Mazloomian 1, Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian 1, Niloufar Borhani Yazdi 2, Mohammad Hassan Ehrampoush 1, Farzan Madadizadeh 3, Maryam Gholami 4,1*

1 Environmental Sciences and Technology Research Center, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2 Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3 Medical Informatics Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

4 Genetics and Environmental Hazards Research Center, Abarkouh School of Medical Sciences, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Mahla Mazloomian 1, Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian 1, Niloufar Borhani Yazdi 2, Mohammad Hassan Ehrampoush 1, Farzan Madadizadeh 3, Maryam Gholami 4,1*

1 Environmental Sciences and Technology Research Center, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2 Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3 Medical Informatics Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

4 Genetics and Environmental Hazards Research Center, Abarkouh School of Medical Sciences, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

| A R T I C L E I N F O | ABSTRACT | |

| SYSTEMATIC REVIEW | Introduction: Dental amalgam, a mercury-based restorative material, is a significant point source of environmental mercury contamination in clinical wastewater. Mercury and other heavy metals from dental clinics enter wastewater systems untreated, posing risks to ecosystems and human health. This review uniquely bridges the critical gap between dental practice effluent pathways, quantitative environmental risk assessment, and practical evaluation of mitigation technologies. Methods and Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted using Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Embase for publications from 2000 to 2024. This review focused on studies quantifying mercury in dental wastewater and evaluated the effectiveness of containment, treatment, and policy measures. Results: The findings confirmed that dental clinics contribute substantially to mercury loads in wastewater, with a single chair releasing as much as 4.5 g/day. Reported mercury concentrations in dental effluent vary widely, ranging from 0.90 µg/L to 39 mg/L, reflecting differences in clinical practices and control measures. The primary mitigation technology is amalgam separators, which can remove more than 90% of amalgam particles and are increasingly required by regulations, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2017. A multi-faceted approach combining separators, optimized chairside practices, waste segregation, and staff education is essential for effective management. Conclusion: Despite the declining use of dental amalgam, it remains an important environmental concern. Effective mitigation requires a combination of stringent policies, proven technologies, and professional stewardship. Future efforts should prioritize standardized monitoring, long-term performance data on control measures, and robust cost-benefit analyses to guide sustainable dental practices. |

|

Article History: Received: 11 August 2025 Accepted: 20 October 2025 |

||

*Corresponding Author: Maryam Gholami Email: gholami313114@gmail.com Tel: +98 35 32838083 |

||

Keywords: Dental Amalgam, Mercury, Dental Unit Wastewater, Amalgam Separator, Environmental Pollution, Wastewater Management. |

Citation: Mazloomian M, Ghaneian MT, Borhani Yazdi N, et al. Dental Amalgam-Derived Mercury in Wastewater: A Systematic Review of Environmental and Health Impacts, and Control Strategies. J Environ Health Sustain Dev. 2025; 10(4): 2804-14.

Introduction

Beyond its essential role in maintaining health, dentistry can also release a wide range of microbial and chemical pollutants into the environment 1, 2. Dental clinic wastewater is legally classified as domestic wastewater and is therefore discharged directly into the urban sewer system without prior treatment, contributing to environmental pollution 3. A prominent recent concern is heavy metal pollution of water resources from dental practices, particularly due to dental amalgam waste. Dental wastewater, generated from the use of amalgam and chemical solutions used to process radiographic films, contains a range of heavy metals, including mercury, silver, tin, nickel, lead, copper, chromium, and cadmium 4, 5. These heavy metals are not only potentially carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, and allergenic to humans but also highly toxic to the environment 6. Amalgam is a dental filling material composed of mercury, silver, and tin, with small amounts of copper and zinc. It has been widely used in dentistry since the early nineteenth century 7. The main constituents of dental amalgam, by mass, are mercury (42–52%), silver (20–34%), tin (8–15%), copper (1–15%), and other metals (0–5%) 8, 9. Of the 10,000 tons of mercury produced worldwide in 1973 and allocated for industrial use, approximately 300 tons were employed in dentistry 4, 8. According to the literature, dentistry is the second largest consumer of mercury, using approximately 70 tons annually in the European :union: 4. Dental-unit wastewater is increasingly recognized as a significant source of anthropogenic mercury emissions, prompting efforts to regulate mercury discharges from dental offices across the United States 10.

Amalgam, a mercury-containing restorative material, is widely used by dentists to repair tooth structures. Consequently, the placement and removal of amalgam restorations can contaminate wastewater discharged from dental facilities with mercury 10. Consequently, dental clinics are considered a major source of mercury discharge into the environment. The European Waste Catalogue classifies dental amalgam waste as hazardous 7, 8. The Minamata Convention on Mercury (2013) compiled substantial evidence of the global adverse impacts of mercury and prompted regulations to manage its use and environmental fate, with particular emphasis on reducing the use of mercury-containing dental amalgams. However, the Technical Background Report for the Global Mercury Assessment estimated that approximately 75 tons of mercury-containing amalgams are still used annually in the European :union:, with approximately 45 tons per year entering dental surgery effluents. Mercury in dental amalgam binds to alloy particles to form a strong and durable restoration. People with amalgam fillings also excrete substantially more mercury in their feces, approximately ten times more than those without amalgam fillings. Based on data from the International Academy of Oral Medicine and Toxicology, it is estimated that more than 8 tons of mercury are discharged annually into rivers, streams, and lakes in the United States 11. Dental amalgam is of concern because roughly half of its mass is mercury, a metal that is highly mobile in the environment, bioaccumulates in the food chain, and is associated with well-documented health risks 8, 12. Dental amalgam particles, whether produced during the placement or removal of fillings, are often disposed of via sewer systems or as municipal waste streams, contaminating water and soil. Mercury is known to be neurotoxic and nephrotoxic7, 10. Despite advances in dental materials and wastewater management, evidence of mercury exposure from dental amalgam in clinical effluents and the effectiveness of sustainable control measures remain fragmented. Prior reviews have often focused on amalgam toxicity or general mercury pollution, offering limited integration of dental clinic wastewater pathways, exposure assessment, and treatment technologies. This review synthesizes multidisciplinary evidence to achieve three primary objectives. First, we quantified the magnitude and variability of mercury concentrations in dental clinic wastewater and assessed the resulting environmental and human health risks. Second, to critically evaluate the efficacy of prevailing management strategies, with a specific focus on amalgam separators, chairside practices, and the effects of regulatory frameworks. Third, to identify persistent knowledge gaps and practical barriers, such as the lack of standardized monitoring and long-term performance data, which hinder optimal implementation. While previous reviews have often focused solely on dental amalgam toxicity or general mercury pollution cycles, this systematic review offers a novel, integrative synthesis. This study uniquely bridges the critical gap between dental practice effluent pathways, quantitative environmental risk assessment, and practical evaluation of mitigation technologies.

Our study is distinctive in three ways. First, it systematically consolidates and analyzes the global range of reported mercury concentrations in dental wastewater, highlighting the sources of variability. Second, it provides a critical, evidence-based appraisal of the real-world efficacy and economic feasibility of amalgam separators and other management strategies. Third, it explicitly links these findings to regulatory frameworks (for example, the Minamata Convention, U.S. EPA rule) to identify actionable knowledge gaps and barriers to sustainability. This holistic approach yields a consolidated evidence base for informing clinicians, regulators, and environmental engineers.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparent literature identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was performed in Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Embase for studies published between 2000 and 2024. The search strategy included combinations of controlled vocabulary (MeSH) and free-text terms across three conceptual domains: a comprehensive search string was developed to capture the intersection of three key conceptual blocks: Dental Amalgam and Mercury (e.g., “dental amalgam,” “mercury release,” “amalgam waste,” “mercury pollution”), Wastewater Context (e.g., “dental wastewater,” “effluent,” “waste water,” “dental unit effluent”), and Management Strategies (e.g., “amalgam separator,” “wastewater treatment,” “removal efficiency,” “mercury capture,” “policy”). The reference lists of the included papers and key regulatory reports (EPA, EU guidelines, and Minamata Convention documents) were manually screened to identify additional sources.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined using the Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework for systematic reviews to ensure relevance and focus.

Beyond its essential role in maintaining health, dentistry can also release a wide range of microbial and chemical pollutants into the environment 1, 2. Dental clinic wastewater is legally classified as domestic wastewater and is therefore discharged directly into the urban sewer system without prior treatment, contributing to environmental pollution 3. A prominent recent concern is heavy metal pollution of water resources from dental practices, particularly due to dental amalgam waste. Dental wastewater, generated from the use of amalgam and chemical solutions used to process radiographic films, contains a range of heavy metals, including mercury, silver, tin, nickel, lead, copper, chromium, and cadmium 4, 5. These heavy metals are not only potentially carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, and allergenic to humans but also highly toxic to the environment 6. Amalgam is a dental filling material composed of mercury, silver, and tin, with small amounts of copper and zinc. It has been widely used in dentistry since the early nineteenth century 7. The main constituents of dental amalgam, by mass, are mercury (42–52%), silver (20–34%), tin (8–15%), copper (1–15%), and other metals (0–5%) 8, 9. Of the 10,000 tons of mercury produced worldwide in 1973 and allocated for industrial use, approximately 300 tons were employed in dentistry 4, 8. According to the literature, dentistry is the second largest consumer of mercury, using approximately 70 tons annually in the European :union: 4. Dental-unit wastewater is increasingly recognized as a significant source of anthropogenic mercury emissions, prompting efforts to regulate mercury discharges from dental offices across the United States 10.

Amalgam, a mercury-containing restorative material, is widely used by dentists to repair tooth structures. Consequently, the placement and removal of amalgam restorations can contaminate wastewater discharged from dental facilities with mercury 10. Consequently, dental clinics are considered a major source of mercury discharge into the environment. The European Waste Catalogue classifies dental amalgam waste as hazardous 7, 8. The Minamata Convention on Mercury (2013) compiled substantial evidence of the global adverse impacts of mercury and prompted regulations to manage its use and environmental fate, with particular emphasis on reducing the use of mercury-containing dental amalgams. However, the Technical Background Report for the Global Mercury Assessment estimated that approximately 75 tons of mercury-containing amalgams are still used annually in the European :union:, with approximately 45 tons per year entering dental surgery effluents. Mercury in dental amalgam binds to alloy particles to form a strong and durable restoration. People with amalgam fillings also excrete substantially more mercury in their feces, approximately ten times more than those without amalgam fillings. Based on data from the International Academy of Oral Medicine and Toxicology, it is estimated that more than 8 tons of mercury are discharged annually into rivers, streams, and lakes in the United States 11. Dental amalgam is of concern because roughly half of its mass is mercury, a metal that is highly mobile in the environment, bioaccumulates in the food chain, and is associated with well-documented health risks 8, 12. Dental amalgam particles, whether produced during the placement or removal of fillings, are often disposed of via sewer systems or as municipal waste streams, contaminating water and soil. Mercury is known to be neurotoxic and nephrotoxic7, 10. Despite advances in dental materials and wastewater management, evidence of mercury exposure from dental amalgam in clinical effluents and the effectiveness of sustainable control measures remain fragmented. Prior reviews have often focused on amalgam toxicity or general mercury pollution, offering limited integration of dental clinic wastewater pathways, exposure assessment, and treatment technologies. This review synthesizes multidisciplinary evidence to achieve three primary objectives. First, we quantified the magnitude and variability of mercury concentrations in dental clinic wastewater and assessed the resulting environmental and human health risks. Second, to critically evaluate the efficacy of prevailing management strategies, with a specific focus on amalgam separators, chairside practices, and the effects of regulatory frameworks. Third, to identify persistent knowledge gaps and practical barriers, such as the lack of standardized monitoring and long-term performance data, which hinder optimal implementation. While previous reviews have often focused solely on dental amalgam toxicity or general mercury pollution cycles, this systematic review offers a novel, integrative synthesis. This study uniquely bridges the critical gap between dental practice effluent pathways, quantitative environmental risk assessment, and practical evaluation of mitigation technologies.

Our study is distinctive in three ways. First, it systematically consolidates and analyzes the global range of reported mercury concentrations in dental wastewater, highlighting the sources of variability. Second, it provides a critical, evidence-based appraisal of the real-world efficacy and economic feasibility of amalgam separators and other management strategies. Third, it explicitly links these findings to regulatory frameworks (for example, the Minamata Convention, U.S. EPA rule) to identify actionable knowledge gaps and barriers to sustainability. This holistic approach yields a consolidated evidence base for informing clinicians, regulators, and environmental engineers.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparent literature identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was performed in Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Embase for studies published between 2000 and 2024. The search strategy included combinations of controlled vocabulary (MeSH) and free-text terms across three conceptual domains: a comprehensive search string was developed to capture the intersection of three key conceptual blocks: Dental Amalgam and Mercury (e.g., “dental amalgam,” “mercury release,” “amalgam waste,” “mercury pollution”), Wastewater Context (e.g., “dental wastewater,” “effluent,” “waste water,” “dental unit effluent”), and Management Strategies (e.g., “amalgam separator,” “wastewater treatment,” “removal efficiency,” “mercury capture,” “policy”). The reference lists of the included papers and key regulatory reports (EPA, EU guidelines, and Minamata Convention documents) were manually screened to identify additional sources.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined using the Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework for systematic reviews to ensure relevance and focus.

- Population/Subject: Dental clinic wastewater effluent, sludge, and related environmental samples.

- Concept: Release, quantification, fate, transport, environmental impact, health risk assessment, and/or management (including technological, operational, or policy measures) of mercury from dental amalgam.

- Context: Studies from any geographic region published in peer-reviewed literature or as official regulatory guidelines.

Inclusion Criteria: Primary studies (observational and experimental) and review articles that directly addressed the PCC framework. Relevant gray literature (e.g., government reports and technical standards) was also included.

Exclusion Criteria: Studies focusing solely on general mercury pollution without a direct link to dental sources, in vitro biocompatibility studies of amalgam that do not involve effluent, conference abstracts, editorials, and articles not available in full text.

Study Selection

All records were imported into EndNote software, and duplicates were removed. Screening proceeded in three stages: (1) title and abstract screening to exclude clearly irrelevant records, (2) full-text review of potentially relevant studies against the eligibility criteri,; and (3) discrepancy resolution by a third reviewer. A PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion is provided (Figure 1).

Exclusion Criteria: Studies focusing solely on general mercury pollution without a direct link to dental sources, in vitro biocompatibility studies of amalgam that do not involve effluent, conference abstracts, editorials, and articles not available in full text.

Study Selection

All records were imported into EndNote software, and duplicates were removed. Screening proceeded in three stages: (1) title and abstract screening to exclude clearly irrelevant records, (2) full-text review of potentially relevant studies against the eligibility criteri,; and (3) discrepancy resolution by a third reviewer. A PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion is provided (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of study selection.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The following data were extracted from each included study:

The following data were extracted from each included study:

- Study design and geographic location

- Measurement methods

- Mercury concentration levels

- Type of wastewater or environmental sample

- Mitigation or treatment strategies assessed

- Key findings and limitations

Data were synthesized narratively because of heterogeneity in the study designs, measurement techniques, and reporting formats.

Results

Magnitude of Mercury Release from Dental Amalgam

Dental amalgam has been used as a restorative material for more than 150 years and is a notable source of mercury in wastewater. Historical data illustrate its widespread use; in 1991, amalgam accounted for 70–80% of single-tooth restorations in the United States, corresponding to an annual consumption of 90–100 tons. Although the estimated consumption declined to 48–50 tons by 2001, the environmental burden persisted. Research indicates that the Dental Wastewater (DWW) stream can contribute approximately 10–70% of the total daily mercury load entering wastewater treatment facilities 13, 14. This waste stream consists primarily of amalgam particles ranging from visible fragments to sub-micron colloidal suspensions. Studies quantifying mercury at the source have reported substantial generation rates. Research from the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and the Naval Dental Research Institute (NDRI) found that a single dental chair can produce up to 4.5 g of mercury per day 13. A parallel Danish study estimated annual discharges of 100–200 g of mercury per dental office 13. Although amalgam waste from dental practices is estimated to account for less than 1% of the total global anthropogenic mercury emissions, its direct discharge into the environment and the increasing pressure to prohibit its use underscore the critical need for effective management 7.

Documented Concentrations of Mercury and Co-contaminants

The use of mercury in dental amalgams is its most common application, despite its well-documented adverse effects on human health and the environment 3. Analysis of dental clinic wastewater revealed substantial variability in mercury concentrations, reflecting differences in clinical practices, sampling methods, and regional contexts. Composite fluid samples from dental clinics showed mean concentrations of 5.3 mg/L for mercury, along with other amalgam constituents: 0.49 mg/L silver, 3.0 mg/L tin, 10.0 mg/L copper, and 76.7 mg/L zinc 3. An assessment of wastewater from 253 dental units at Shahid Beheshti University’s Dentistry School in Iran reported a mercury concentration of 9.0 µg/L, with other heavy metals present at 110.6 µg/L lead, 53.3 µg/L cadmium, 663.5 µg/L copper, and 91.1 µg/L nickel 3. A preliminary study from Aguascalientes, Mexico, reported potentially high concentrations of mercury (8–39 mg/L), arsenic (1–3 mg/L), and fluoride (1–7 mg/L), exceeding local regulatory limits3. A synthesis of the reported mercury concentrations from various studies is presented in Table 1, illustrating the wide range observed in the scientific literature.

Results

Magnitude of Mercury Release from Dental Amalgam

Dental amalgam has been used as a restorative material for more than 150 years and is a notable source of mercury in wastewater. Historical data illustrate its widespread use; in 1991, amalgam accounted for 70–80% of single-tooth restorations in the United States, corresponding to an annual consumption of 90–100 tons. Although the estimated consumption declined to 48–50 tons by 2001, the environmental burden persisted. Research indicates that the Dental Wastewater (DWW) stream can contribute approximately 10–70% of the total daily mercury load entering wastewater treatment facilities 13, 14. This waste stream consists primarily of amalgam particles ranging from visible fragments to sub-micron colloidal suspensions. Studies quantifying mercury at the source have reported substantial generation rates. Research from the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and the Naval Dental Research Institute (NDRI) found that a single dental chair can produce up to 4.5 g of mercury per day 13. A parallel Danish study estimated annual discharges of 100–200 g of mercury per dental office 13. Although amalgam waste from dental practices is estimated to account for less than 1% of the total global anthropogenic mercury emissions, its direct discharge into the environment and the increasing pressure to prohibit its use underscore the critical need for effective management 7.

Documented Concentrations of Mercury and Co-contaminants

The use of mercury in dental amalgams is its most common application, despite its well-documented adverse effects on human health and the environment 3. Analysis of dental clinic wastewater revealed substantial variability in mercury concentrations, reflecting differences in clinical practices, sampling methods, and regional contexts. Composite fluid samples from dental clinics showed mean concentrations of 5.3 mg/L for mercury, along with other amalgam constituents: 0.49 mg/L silver, 3.0 mg/L tin, 10.0 mg/L copper, and 76.7 mg/L zinc 3. An assessment of wastewater from 253 dental units at Shahid Beheshti University’s Dentistry School in Iran reported a mercury concentration of 9.0 µg/L, with other heavy metals present at 110.6 µg/L lead, 53.3 µg/L cadmium, 663.5 µg/L copper, and 91.1 µg/L nickel 3. A preliminary study from Aguascalientes, Mexico, reported potentially high concentrations of mercury (8–39 mg/L), arsenic (1–3 mg/L), and fluoride (1–7 mg/L), exceeding local regulatory limits3. A synthesis of the reported mercury concentrations from various studies is presented in Table 1, illustrating the wide range observed in the scientific literature.

Table 1: Concentration of mercury in dental wastewater

| Heavy metals species | Concentration | Reference |

| Mercury (μg/L) | 1.0 | 3 |

| Mercury (mg/L) | 5.3 | 3 |

| Mercury (μg/mL) | 0.2–2.0 | 15 |

| Mercury (μg/L) | 5.3 - 9.0 | 16 |

| Methyl Mercury (μg/L) | 45182.11 | 17 |

| Mercury (mg/L) | 8 – 39 | 18 |

| Mercury (μg/L) | 0.90 | 17 |

| Mercury (μg/L) | 5.3 ± 11.1 | 8 |

| Methyl Mercury (μg/L) | 0.33 ( ± 0.06) | 19 |

| Mercury (μg/L) | 471.69 | 20 |

| Total Mercury (μg/L) | 2.27 ( ± 0.13) | 19 |

| Mercury (ng/L) | 23.1 | 19 |

Mercury toxicity and health implications

Mercury is a potent heavy metal, and its toxicity is dependent on its chemical form (elemental (Hg⁰), inorganic (Hg²⁺), or organic (notably methylmercury (MeHg))) and its route of exposure 21. Elemental mercury vapor, common in occupational settings such as dentistry and mining, primarily affects the nervous and respiratory systems 21. Although inorganic mercury is less readily absorbed, it can cause nephrotoxicity, gastrointestinal symptoms, and systemic toxicity at high doses. MeHg often acquired through contaminated fish, MeHg readily crosses the placental and blood-brain barriers. Prenatal exposure is associated with persistent neurodevelopmental impairments, including cognitive, motor, and language deficits. In adults, it can disrupt sensory processing, motor coordination, and executive function 22-24. At the molecular level, mercury's high affinity for sulfhydryl groups disrupts protein function and enzyme activity, inducing oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation, which lead to neuronal and renal damage. Epigenetic modifications may mediate long-term neurobehavioral outcomes. Inorganic mercury can be methylated in aquatic systems by anaerobic microbes; the resulting MeHg bioaccumulates and biomagnifies in the food web, posing significant risks to ecosystems and human health 25-27. Even at lower doses, mercury exposure can cause irritability, social withdrawal, tremors, sensory alterations, and memory impairments 10, 28.

Regulatory framework and management strategies

In response to these documented risks, regulatory bodies have established strict limits. The U.S. EPA has set a maximum permissible dose for mercury in wastewater at 0.1 mg/L and classifies amalgam waste as special waste 4, 29. A pivotal regulatory action was the 2017 EPA final rule requiring dental offices to install amalgam separators, with a compliance deadline of July 14, 2020 5, 30. A multifaceted approach to mitigate mercury release from dentistry has been proposed and implemented, as outlined in Table 2 31-34.

Table 2: Multi-faceted strategies for mitigating mercury releases from dentistry

| Key Component | Description |

| Source reduction | Public health and regulatory responses emphasize source reduction, exposure monitoring, and risk communication. Occupational exposure limits, safer handling practices in dental settings, and rigorous remediation of contaminated sites mitigate human risk. |

| Chairside practices and waste handling | Using mercury-free mixing devices, employ minimal- drill techniques, strictly segregate and properly store amalgam waste, and establishing clear on-site protocols for handling extracted amalgam-containing materials. |

| Amalgam containment and capture | Installing high-efficiency amalgam separators that comply with standards and ensure their regular maintenance. |

| Wastewater treatment and environmental controls | Employing advanced treatment technologies at the clinic level (e.g., adsorption, advanced oxidation, ion exchange, activated carbon) connect to centralized treatment plants with mercury removal capabilities; conduct periodic effluent monitoring. |

| Policy and economic measures | Tightening regulations on amalgam use, waste management, and disposal; requiring auditing of amalgam waste and separators, promoting recycling programs, and providing subsidies for small practices to invest in compliant technology. |

| Education and research | Develop continuing education on mercury stewardship and investing in standardized monitoring and innovative treatment technologies. |

Economic considerations of amalgam separation equipment

The adoption of amalgam separators requires a defined capital investment in dental practices. The costs depend on the device type (separator, trap, or combined system), installation complexity, and maintenance requirements. Universal amalgam separators are often cost-effective to retrofit, while more sophisticated integrated systems may have higher initial costs but offer improved capture efficiency and reduced regulatory liability 29, 35, 36. The total cost of ownership includes the purchase price, installation, potential renovations (and any necessary renovations), periodic filter replacement, and routine maintenance. Lifecycle cost analyses indicate that the investment is often justified, with payback periods ranging from a few months to several years, contingent on clinic size and patient volume. Economic benefits come from avoiding regulatory fines, reducing environmental liability, and achieving long-term operational efficiencies 37, 38.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review demonstrate that dental clinics are significant point sources of mercury contamination in municipal wastewater systems. Although amalgam use has declined from 70–80% of restorations in 1991 13 to much lower levels today, the environmental burden persists. Data indicating that a single dental chair can produce up to 4.5 g of mercury daily 13 underscore the intensity of the localized release. Although the global anthropogenic contribution of dental mercury may be less than 1% 7, its direct pathway into municipal wastewater systems-accounting for 10-70% of the daily load entering some treatment plants 13, 14, making it a pollutant of high concern. One notable finding was the substantial contribution of particulate-bound mercury from the removal or polishing of dental amalgam restorations. Several studies have confirmed that mercury in dental wastewater binds to fine particulates that are easily mobilized into sewer systems. These particles are not adequately removed by conventional sewer systems and can be carried to wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), where some accumulate in sludge while other fractions remain in the effluent. This agrees with earlier findings that WWTPs are not designed to efficiently remove mercury, particularly in its particulate and ionic forms11.

Analytical variability and toxicological significance

The extreme variability in reported mercury concentrations, from as low as 0.90 µg/L 10 to as high as 39 mg/L 18, highlights a critical challenge in the risk assessment. This variability, summarized in Table 1, likely reflects differences in clinical practices, sampling methods, and, crucially, the presence and effectiveness of the amalgam capture technologies. The reported presence of other amalgam constituents, such as silver, copper, and tin 3, confirms that dental wastewater carries a complex mixture of heavy metals and not just mercury. The toxicological profile of mercury, which depends on its chemical form, adds another layer of complexity. The high neurotoxicity of MeHg, particularly its effects on prenatal neurodevelopment 22-24, is well established. The environmental implications of this are noteworthy. Elemental mercury (Hg⁰) and inorganic mercury (Hg²⁺) discharged from dental units can undergo microbial methylation in aquatic environments. Methylmercury (MeHg), the most toxic and bioaccumulative mercury species, poses severe ecological and neurodevelopmental risks 25-27.

The efficacy and economics of mitigation technologies

In response, regulatory frameworks have evolved, culminating in mandates such as the 2017 EPA rule in the U.S., which requires amalgam separators 5, 30. The multifaceted management strategies outlined in Table 2 are essential. The primary technological intervention is the amalgam separator, a device widely implemented in European nations such as Sweden, Germany, and Denmark 13, 39.

These devices, which operate on the principles of sedimentation and filtration in wet or dry suction systems 12, 37 have shown promising removal efficiencies. The Seattle pilot study, for example, showed that filtration and gravity settling can achieve over 90% mercury removal 13, 40. However, their real-world performance is not infallible; they are sensitive to flow peaks and require proper maintenance to prevent the resuspension of settled amalgam 12. The economic feasibility of this technology is supported by lifecycle cost analyses, which suggest that the initial investment is often offset by avoided regulatory fines, long-term operational efficiencies, and payback periods that vary by clinic size 37, 38. Consistent with prior evaluations, this review found that properly installed and maintained amalgam separators substantially reduce mercury discharge. These findings underscore the importance of routine inspections, staff training, and regulatory enforcement. While the results support the effectiveness of existing policies, they also reveal gaps, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where financial constraints, limited enforcement, and a lack of awareness hinder implementation.

Research gaps and a framework for sustainable management

Despite these advances, significant research gaps remain in the optimal management of these patients. There is a pronounced lack of standardization in sampling and analysis across studies, which limits their comparability. Long-term, real-world performance data for amalgam separators across diverse clinical workflows are scarce, making it difficult to assess the true lifecycle costs and benefits 41, 42. Furthermore, data linking on-site mercury capture to tangible improvements in environmental and human health outcomes are fragmented and limited. There is a clear need for more robust cost-benefit analyses of mercury-free alternatives and empirical evaluations of regulatory enforcement mechanisms 43. Strengthening surveillance systems, subsidizing separator installation, and integrating dental mercury management into national environmental health strategies could improve compliance with the law. Addressing these gaps aligns with the broader systemic approach required by the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 44-46. Sustainable healthcare requires a multi-level, inter-sectoral framework that links clinical practice with environmental health 47-49. Therefore, the path forward requires more than just technology installation. This demands a holistic strategy that integrates stringent policies, continuous education, standardized waste auditing, and a commitment to translating guidelines into consistent global practice. This will ensure that mercury management in dentistry evolves from a regulatory compliance issue to a cornerstone of sustainable and environmentally responsible healthcare.

Conclusion

This review highlights that dental clinics remain a significant and preventable source of mercury in municipal wastewater. Although amalgam separators substantially reduce mercury discharge, their real-world effectiveness depends on the installation quality, routine maintenance, and regulatory compliance. Mercury released from dental settings poses environmental risks because it is persistent, mobile, and can be microbially transformed into methylmercury, which accumulates in aquatic food webs.

While global policies, particularly those established under the Minamata Convention, have accelerated progress toward mercury reduction, significant implementation disparities remain. Strengthening regulatory enforcement, improving professional training, and ensuring the universal adoption of ISO-compliant separators are essential steps for mitigating mercury pollution from dental sources.

Standardization of sampling protocols and improved monitoring frameworks are urgently needed to reduce inconsistencies in the reported data and better quantify environmental impacts. Future research should integrate clinical, environmental, and regulatory perspectives to support sustainable mercury management in the dental industry.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Student Research Committee, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Grant number 22481. The authors would like to thank the Student Research Committee at Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study is Funded by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Ethical Considerations

This study did not involve human or animal subjects or a systematic review of the published literature; therefore, ethical approval and informed consent were not applicable.

Code of Ethics

The authors affirm that this study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of research integrity and reporting. No ethical approval code was required because of the nature of the study.

Authors contributions

Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian contributed to the conception and design of the study, all authors contributed to the data acquisition, and initial drafting of the manuscript. Mahla Mazloomian, Maryam Gholami, and Niloufar Borhani Yazdi contributed to data analysis, interpretation of the findings, and manuscript revisions. Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian supervised the project and provided critical revisions. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

This is an Open-Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work for commercial use.

References

1. Amalgam (Part 1): [Internet]. Safe Management of Waste and Mercury: Adopted by the FDI General Assembly: 27-29 September 2021, Sydney, Australia. Int Dent J. 2022;72(1):10-1. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi. nlm.nih. gov/35074198/. [cited Feb 11, 2022].

2. Binner H, Kamali N, Harding M, et al. Characteristics of wastewater originating from dental practices using predominantly mercury-free dental materials. Sci Total Environ. 2022;814:152632.

3. Elvir-Padilla LG, Mendoza-Castillo DI, Reynel-Ávila HE, et al. Adsorption of dental clinic pollutants using bone char: adsorbent preparation, assessment and mechanism analysis. Chem Eng Res Des. 2022;183:192-202.

4. Abdolinasab S, Jahani Y, Daraei H. Investigation of heavy metal concentrations in wastewater of dental units: Ecological risks. Desalination Water Treat. 2025;322:101213.

5. Lamsal R, Estrich CG, Sandmann D, et al. Declining US dental amalgam restorations in US food and drug administration–identified populations: 2017-2023. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2024;155(10):816-24.

6. Polydorou O, Schmidt O-C, Spraul M, et al. Detection of Bisphenol A in dental wastewater after grinding of dental resin composites. Dental Materials. 2020;36(8):1009-18.

7. Daou MH, Karam R, Khalil S, et al. Current status of dental waste management in Lebanon. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2015;4:1-5.

8. Shraim A, Alsuhaimi A, Al-Thakafy JT. Dental clinics: a point pollution source, not only of mercury but also of other amalgam constituents. Chemosphere. 2011;84(8):1133-9.

9. Uçar Y, Brantley W. 7 - Biocompatibility of dental amalgams. Biocompatibility of Dental Biomaterials. 2017: 95-111.

10. Stone ME, Scott JW, Schultz ST, et al. Comparison of chlorine and chloramine in the release of mercury from dental amalgam. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407(2):770-5.

11. Albishri HM, Yakout AA. Efficient removal of Hg (II) from dental effluents by thio-functionalized biochar derived from cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana L.) leaves. Mater Chem Phys. 2023;295:127125.

12. Hylander LD, Lindvall A, Uhrberg R, et al. Mercury recovery in situ of four different dental amalgam separators. Sci Total Environ. 2006;366(1):320-36.

13. Drummond JL, Cailas MD, Croke K. Mercury generation potential from dental waste amalgam. Journal of Dentistry. 2003;31(7):493-501.

14. Karim BA, Mahmood G, Hasija M, et al. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in groundwater and its implications for dental and public health. Chemosphere. 2024;367:143609.

15. Hamza A, Bashammakh A, Al-Sibaai A, et al. Spectrophotometric determination of trace mercury (II) in dental-unit wastewater and fertilizer samples using the novel reagent 6-hydroxy-3-(2-oxoindolin-3-ylideneamino)-2-thioxo-2H-1, 3-thiazin-4 (3H)-one and the dual-wavelength β-correction spectrophotometry. J Hazard Mater. 2010;178(1-3):287-92.

16. Ghasemi H, Masoudirad A. Concentrations of heavy metals in wastewater of one of the largest dentistry schools in Iran. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020;11(2):113.

17. Stone ME, Cohen ME, Liang L, et al. Determination of methyl mercury in dental-unit wastewater. Dental Materials. 2003;19(7):675-9.

18. Cataldi M, AL Rakayan S, Arcuri C, et al. Dental unit wastewater, a current environmental problem: a sistematic review. Oral Implantol (Rome). 2017;10(4):354.

19. Zhao X, Rockne KJ, Drummond JL, et al. Characterization of methyl mercury in dental wastewater and correlation with sulfate-reducing bacterial DNA. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(8):2780-6.

20. Batchu H, Chou H-N, Rakowski D, et al. The effect of disinfectants and line cleaners on the release of mercury from amalgam. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2006;137(10): 1419-25.

21.Basu N, Bastiansz A, Dórea JG, et al. Our evolved understanding of the human health risks of mercury. Ambio. 2023;52(5):877-96.

22. de Almeida Rodrigues P, Ferrari RG, Dos Santos LN, et al. Mercury in aquatic fauna contamination: a systematic review on its dynamics and potential health risks. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 2019;84:205-18.

23. Zulaikhah ST, Wahyuwibowo J, Pratama AA. Mercury and its effect on human health: a review of the literature. Int J Publ Health Sci. 2020;9(2):103-14.

24. Zhao H, Yan H, Zhang L, et al. Mercury contents in rice and potential health risks across China. Environ Int. 2019;126:406-12.

25. Felix CS, Junior JBP, da Silva Junior JB, et al. Determination and human health risk assessment of mercury in fish samples. Talanta. 2022;247:123557.

26. Henriques MC, Loureiro S, Fardilha M, et al. Exposure to mercury and human reproductive health: A systematic review. Reproductive Toxicology. 2019;85:93-103.

27. Berlin M. Mercury in dental amalgam: a risk analysis. Neurotoxicology. 2020;81:382-6.

28. Keramati P, Hoodaji M, Tahmourespour A. Multi-metal resistance study of bacteria highly resistant to mercury isolated from dental clinic effluent. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5(7):831-7.

29. Condrin AK. The use of CDA best management practices and amalgam separators to improve the management of dental wastewater. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32(7):583-92.

30. Drummond JL, Liu Y, Wu T-Y, et al. Particle versus mercury removal efficiency of amalgam separators. Journal of Dentistry. 2003;31(1):51-8.

31. Musliu A, Beqa L, Kastrati G. The use of dental amalgam and amalgam waste management in Kosova: An environmental policy approach. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2021;17(5):1037-44.

32. Chin G, Chong J, Kluczewska A, et al. The environmental effects of dental amalgam. Aust Dent J. 2000;45(4):246-9.

33. Arenholt-Bindslev D. Dental amalgam—environmental aspects. Adv Dent Res. 1992;6(1):125-30

34. Fairbanks SD, Pramanik SK, Thomas JA, et al. The management of mercury from dental amalgam in wastewater effluent. Environ Tech Rev. 2021;10(1):213-23.

35. Olivera D, Morgan M, Tewolde S, et al. Clinical evaluation of a chairside amalgam separator to meet environmental protection agency dental wastewater regulatory compliance. Operative Dentistry. 2020;45(2):151-62.

36. Tibau AV, Grube BD. Mercury contamination from dental amalgam. J Health Pollut. 2019;9(22):190612.

37. Jokstad A, Fan P. Amalgam waste management. Int Dent J. 2006;56(3):147-53.

38. Eshrati M, Momeniha F, Momeni N, et al. Clinical guide adaptation for amalgam waste management in dental settings in Iran. Front Dent. 2024;21:44.

39. Pinheiro TN, Consolaro A, Sakuma A, et al. Mercury accumulation in fish: the potential effect of dental amalgam wastewater. International Journal of Experimental Dental Science. 2014;1(2):75-80.

40. Roberts HW, Marek M, Kuehne JC, et al. Disinfectants' effect on mercury release from amalgam. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2005;136(7):915-9.

41. Cailas MD, Drummond JL, Tung-Yi W, et al. Characteristics and treatment of the dental waste water stream. RR Series (Waste Management and Research Center); 097. 2002.

42. Mulligan S, Kakonyi G, Moharamzadeh K, et al. The environmental impact of dental amalgam and resin-based composite materials. Br Dent J. 2018;224(7):542-8.

43. Sudi SM, Naidoo S. Mercury levels in wastewater samples at a South African dental school. S Afr Dent J. 2024;79(9):470-5.

44. Watson P, Adegbembo A, Lugowski S. A study of the fate of mercury from the placement and removal of dental amalgam restorations. Final report Part I: Removal of dental amalgam restorations. Toronto: Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. 2002.

45. Hylander LD, Lindvall A, Gahnberg L. High mercury emissions from dental clinics despite amalgam separators. Sci Total Environ. 2006;362(1-3):74-84.

46. Pichay TJ. Dental amalgam: regulating its use and disposal. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32(7):580-2.

47. Shinkai RS, Biazevic MG, Michel-Crosato E, et al. Environmental sustainability related to dental materials and procedures in prosthodontics: a critical review. J Prosthet Dent. 2025;133(6):1466-73.

48. Hsu CJ, Xiao YZ, Chung A, et al. Novel applications of vacuum distillation for heavy metals removal from wastewater, copper nitrate hydroxide recovery, and copper sulfide impregnated activated carbon synthesis for gaseous mercury adsorption. Sci Total Environ. 2023;855:158870.

49. Dalla Costa R, Cossich ES, Tavares CRG. Influence of the temperature, volume and type of solution in the mercury vaporization of dental amalgam residue. Sci Total Environ. 2008;407(1):1-6.

The adoption of amalgam separators requires a defined capital investment in dental practices. The costs depend on the device type (separator, trap, or combined system), installation complexity, and maintenance requirements. Universal amalgam separators are often cost-effective to retrofit, while more sophisticated integrated systems may have higher initial costs but offer improved capture efficiency and reduced regulatory liability 29, 35, 36. The total cost of ownership includes the purchase price, installation, potential renovations (and any necessary renovations), periodic filter replacement, and routine maintenance. Lifecycle cost analyses indicate that the investment is often justified, with payback periods ranging from a few months to several years, contingent on clinic size and patient volume. Economic benefits come from avoiding regulatory fines, reducing environmental liability, and achieving long-term operational efficiencies 37, 38.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review demonstrate that dental clinics are significant point sources of mercury contamination in municipal wastewater systems. Although amalgam use has declined from 70–80% of restorations in 1991 13 to much lower levels today, the environmental burden persists. Data indicating that a single dental chair can produce up to 4.5 g of mercury daily 13 underscore the intensity of the localized release. Although the global anthropogenic contribution of dental mercury may be less than 1% 7, its direct pathway into municipal wastewater systems-accounting for 10-70% of the daily load entering some treatment plants 13, 14, making it a pollutant of high concern. One notable finding was the substantial contribution of particulate-bound mercury from the removal or polishing of dental amalgam restorations. Several studies have confirmed that mercury in dental wastewater binds to fine particulates that are easily mobilized into sewer systems. These particles are not adequately removed by conventional sewer systems and can be carried to wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), where some accumulate in sludge while other fractions remain in the effluent. This agrees with earlier findings that WWTPs are not designed to efficiently remove mercury, particularly in its particulate and ionic forms11.

Analytical variability and toxicological significance

The extreme variability in reported mercury concentrations, from as low as 0.90 µg/L 10 to as high as 39 mg/L 18, highlights a critical challenge in the risk assessment. This variability, summarized in Table 1, likely reflects differences in clinical practices, sampling methods, and, crucially, the presence and effectiveness of the amalgam capture technologies. The reported presence of other amalgam constituents, such as silver, copper, and tin 3, confirms that dental wastewater carries a complex mixture of heavy metals and not just mercury. The toxicological profile of mercury, which depends on its chemical form, adds another layer of complexity. The high neurotoxicity of MeHg, particularly its effects on prenatal neurodevelopment 22-24, is well established. The environmental implications of this are noteworthy. Elemental mercury (Hg⁰) and inorganic mercury (Hg²⁺) discharged from dental units can undergo microbial methylation in aquatic environments. Methylmercury (MeHg), the most toxic and bioaccumulative mercury species, poses severe ecological and neurodevelopmental risks 25-27.

The efficacy and economics of mitigation technologies

In response, regulatory frameworks have evolved, culminating in mandates such as the 2017 EPA rule in the U.S., which requires amalgam separators 5, 30. The multifaceted management strategies outlined in Table 2 are essential. The primary technological intervention is the amalgam separator, a device widely implemented in European nations such as Sweden, Germany, and Denmark 13, 39.

These devices, which operate on the principles of sedimentation and filtration in wet or dry suction systems 12, 37 have shown promising removal efficiencies. The Seattle pilot study, for example, showed that filtration and gravity settling can achieve over 90% mercury removal 13, 40. However, their real-world performance is not infallible; they are sensitive to flow peaks and require proper maintenance to prevent the resuspension of settled amalgam 12. The economic feasibility of this technology is supported by lifecycle cost analyses, which suggest that the initial investment is often offset by avoided regulatory fines, long-term operational efficiencies, and payback periods that vary by clinic size 37, 38. Consistent with prior evaluations, this review found that properly installed and maintained amalgam separators substantially reduce mercury discharge. These findings underscore the importance of routine inspections, staff training, and regulatory enforcement. While the results support the effectiveness of existing policies, they also reveal gaps, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where financial constraints, limited enforcement, and a lack of awareness hinder implementation.

Research gaps and a framework for sustainable management

Despite these advances, significant research gaps remain in the optimal management of these patients. There is a pronounced lack of standardization in sampling and analysis across studies, which limits their comparability. Long-term, real-world performance data for amalgam separators across diverse clinical workflows are scarce, making it difficult to assess the true lifecycle costs and benefits 41, 42. Furthermore, data linking on-site mercury capture to tangible improvements in environmental and human health outcomes are fragmented and limited. There is a clear need for more robust cost-benefit analyses of mercury-free alternatives and empirical evaluations of regulatory enforcement mechanisms 43. Strengthening surveillance systems, subsidizing separator installation, and integrating dental mercury management into national environmental health strategies could improve compliance with the law. Addressing these gaps aligns with the broader systemic approach required by the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 44-46. Sustainable healthcare requires a multi-level, inter-sectoral framework that links clinical practice with environmental health 47-49. Therefore, the path forward requires more than just technology installation. This demands a holistic strategy that integrates stringent policies, continuous education, standardized waste auditing, and a commitment to translating guidelines into consistent global practice. This will ensure that mercury management in dentistry evolves from a regulatory compliance issue to a cornerstone of sustainable and environmentally responsible healthcare.

Conclusion

This review highlights that dental clinics remain a significant and preventable source of mercury in municipal wastewater. Although amalgam separators substantially reduce mercury discharge, their real-world effectiveness depends on the installation quality, routine maintenance, and regulatory compliance. Mercury released from dental settings poses environmental risks because it is persistent, mobile, and can be microbially transformed into methylmercury, which accumulates in aquatic food webs.

While global policies, particularly those established under the Minamata Convention, have accelerated progress toward mercury reduction, significant implementation disparities remain. Strengthening regulatory enforcement, improving professional training, and ensuring the universal adoption of ISO-compliant separators are essential steps for mitigating mercury pollution from dental sources.

Standardization of sampling protocols and improved monitoring frameworks are urgently needed to reduce inconsistencies in the reported data and better quantify environmental impacts. Future research should integrate clinical, environmental, and regulatory perspectives to support sustainable mercury management in the dental industry.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Student Research Committee, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Grant number 22481. The authors would like to thank the Student Research Committee at Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study is Funded by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Ethical Considerations

This study did not involve human or animal subjects or a systematic review of the published literature; therefore, ethical approval and informed consent were not applicable.

Code of Ethics

The authors affirm that this study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of research integrity and reporting. No ethical approval code was required because of the nature of the study.

Authors contributions

Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian contributed to the conception and design of the study, all authors contributed to the data acquisition, and initial drafting of the manuscript. Mahla Mazloomian, Maryam Gholami, and Niloufar Borhani Yazdi contributed to data analysis, interpretation of the findings, and manuscript revisions. Mohammad Taghi Ghaneian supervised the project and provided critical revisions. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

This is an Open-Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work for commercial use.

References

1. Amalgam (Part 1): [Internet]. Safe Management of Waste and Mercury: Adopted by the FDI General Assembly: 27-29 September 2021, Sydney, Australia. Int Dent J. 2022;72(1):10-1. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi. nlm.nih. gov/35074198/. [cited Feb 11, 2022].

2. Binner H, Kamali N, Harding M, et al. Characteristics of wastewater originating from dental practices using predominantly mercury-free dental materials. Sci Total Environ. 2022;814:152632.

3. Elvir-Padilla LG, Mendoza-Castillo DI, Reynel-Ávila HE, et al. Adsorption of dental clinic pollutants using bone char: adsorbent preparation, assessment and mechanism analysis. Chem Eng Res Des. 2022;183:192-202.

4. Abdolinasab S, Jahani Y, Daraei H. Investigation of heavy metal concentrations in wastewater of dental units: Ecological risks. Desalination Water Treat. 2025;322:101213.

5. Lamsal R, Estrich CG, Sandmann D, et al. Declining US dental amalgam restorations in US food and drug administration–identified populations: 2017-2023. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2024;155(10):816-24.

6. Polydorou O, Schmidt O-C, Spraul M, et al. Detection of Bisphenol A in dental wastewater after grinding of dental resin composites. Dental Materials. 2020;36(8):1009-18.

7. Daou MH, Karam R, Khalil S, et al. Current status of dental waste management in Lebanon. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2015;4:1-5.

8. Shraim A, Alsuhaimi A, Al-Thakafy JT. Dental clinics: a point pollution source, not only of mercury but also of other amalgam constituents. Chemosphere. 2011;84(8):1133-9.

9. Uçar Y, Brantley W. 7 - Biocompatibility of dental amalgams. Biocompatibility of Dental Biomaterials. 2017: 95-111.

10. Stone ME, Scott JW, Schultz ST, et al. Comparison of chlorine and chloramine in the release of mercury from dental amalgam. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407(2):770-5.

11. Albishri HM, Yakout AA. Efficient removal of Hg (II) from dental effluents by thio-functionalized biochar derived from cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana L.) leaves. Mater Chem Phys. 2023;295:127125.

12. Hylander LD, Lindvall A, Uhrberg R, et al. Mercury recovery in situ of four different dental amalgam separators. Sci Total Environ. 2006;366(1):320-36.

13. Drummond JL, Cailas MD, Croke K. Mercury generation potential from dental waste amalgam. Journal of Dentistry. 2003;31(7):493-501.

14. Karim BA, Mahmood G, Hasija M, et al. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in groundwater and its implications for dental and public health. Chemosphere. 2024;367:143609.

15. Hamza A, Bashammakh A, Al-Sibaai A, et al. Spectrophotometric determination of trace mercury (II) in dental-unit wastewater and fertilizer samples using the novel reagent 6-hydroxy-3-(2-oxoindolin-3-ylideneamino)-2-thioxo-2H-1, 3-thiazin-4 (3H)-one and the dual-wavelength β-correction spectrophotometry. J Hazard Mater. 2010;178(1-3):287-92.

16. Ghasemi H, Masoudirad A. Concentrations of heavy metals in wastewater of one of the largest dentistry schools in Iran. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020;11(2):113.

17. Stone ME, Cohen ME, Liang L, et al. Determination of methyl mercury in dental-unit wastewater. Dental Materials. 2003;19(7):675-9.

18. Cataldi M, AL Rakayan S, Arcuri C, et al. Dental unit wastewater, a current environmental problem: a sistematic review. Oral Implantol (Rome). 2017;10(4):354.

19. Zhao X, Rockne KJ, Drummond JL, et al. Characterization of methyl mercury in dental wastewater and correlation with sulfate-reducing bacterial DNA. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(8):2780-6.

20. Batchu H, Chou H-N, Rakowski D, et al. The effect of disinfectants and line cleaners on the release of mercury from amalgam. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2006;137(10): 1419-25.

21.Basu N, Bastiansz A, Dórea JG, et al. Our evolved understanding of the human health risks of mercury. Ambio. 2023;52(5):877-96.

22. de Almeida Rodrigues P, Ferrari RG, Dos Santos LN, et al. Mercury in aquatic fauna contamination: a systematic review on its dynamics and potential health risks. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 2019;84:205-18.

23. Zulaikhah ST, Wahyuwibowo J, Pratama AA. Mercury and its effect on human health: a review of the literature. Int J Publ Health Sci. 2020;9(2):103-14.

24. Zhao H, Yan H, Zhang L, et al. Mercury contents in rice and potential health risks across China. Environ Int. 2019;126:406-12.

25. Felix CS, Junior JBP, da Silva Junior JB, et al. Determination and human health risk assessment of mercury in fish samples. Talanta. 2022;247:123557.

26. Henriques MC, Loureiro S, Fardilha M, et al. Exposure to mercury and human reproductive health: A systematic review. Reproductive Toxicology. 2019;85:93-103.

27. Berlin M. Mercury in dental amalgam: a risk analysis. Neurotoxicology. 2020;81:382-6.

28. Keramati P, Hoodaji M, Tahmourespour A. Multi-metal resistance study of bacteria highly resistant to mercury isolated from dental clinic effluent. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5(7):831-7.

29. Condrin AK. The use of CDA best management practices and amalgam separators to improve the management of dental wastewater. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32(7):583-92.

30. Drummond JL, Liu Y, Wu T-Y, et al. Particle versus mercury removal efficiency of amalgam separators. Journal of Dentistry. 2003;31(1):51-8.

31. Musliu A, Beqa L, Kastrati G. The use of dental amalgam and amalgam waste management in Kosova: An environmental policy approach. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2021;17(5):1037-44.

32. Chin G, Chong J, Kluczewska A, et al. The environmental effects of dental amalgam. Aust Dent J. 2000;45(4):246-9.

33. Arenholt-Bindslev D. Dental amalgam—environmental aspects. Adv Dent Res. 1992;6(1):125-30

34. Fairbanks SD, Pramanik SK, Thomas JA, et al. The management of mercury from dental amalgam in wastewater effluent. Environ Tech Rev. 2021;10(1):213-23.

35. Olivera D, Morgan M, Tewolde S, et al. Clinical evaluation of a chairside amalgam separator to meet environmental protection agency dental wastewater regulatory compliance. Operative Dentistry. 2020;45(2):151-62.

36. Tibau AV, Grube BD. Mercury contamination from dental amalgam. J Health Pollut. 2019;9(22):190612.

37. Jokstad A, Fan P. Amalgam waste management. Int Dent J. 2006;56(3):147-53.

38. Eshrati M, Momeniha F, Momeni N, et al. Clinical guide adaptation for amalgam waste management in dental settings in Iran. Front Dent. 2024;21:44.

39. Pinheiro TN, Consolaro A, Sakuma A, et al. Mercury accumulation in fish: the potential effect of dental amalgam wastewater. International Journal of Experimental Dental Science. 2014;1(2):75-80.

40. Roberts HW, Marek M, Kuehne JC, et al. Disinfectants' effect on mercury release from amalgam. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2005;136(7):915-9.

41. Cailas MD, Drummond JL, Tung-Yi W, et al. Characteristics and treatment of the dental waste water stream. RR Series (Waste Management and Research Center); 097. 2002.

42. Mulligan S, Kakonyi G, Moharamzadeh K, et al. The environmental impact of dental amalgam and resin-based composite materials. Br Dent J. 2018;224(7):542-8.

43. Sudi SM, Naidoo S. Mercury levels in wastewater samples at a South African dental school. S Afr Dent J. 2024;79(9):470-5.

44. Watson P, Adegbembo A, Lugowski S. A study of the fate of mercury from the placement and removal of dental amalgam restorations. Final report Part I: Removal of dental amalgam restorations. Toronto: Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. 2002.

45. Hylander LD, Lindvall A, Gahnberg L. High mercury emissions from dental clinics despite amalgam separators. Sci Total Environ. 2006;362(1-3):74-84.

46. Pichay TJ. Dental amalgam: regulating its use and disposal. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32(7):580-2.

47. Shinkai RS, Biazevic MG, Michel-Crosato E, et al. Environmental sustainability related to dental materials and procedures in prosthodontics: a critical review. J Prosthet Dent. 2025;133(6):1466-73.

48. Hsu CJ, Xiao YZ, Chung A, et al. Novel applications of vacuum distillation for heavy metals removal from wastewater, copper nitrate hydroxide recovery, and copper sulfide impregnated activated carbon synthesis for gaseous mercury adsorption. Sci Total Environ. 2023;855:158870.

49. Dalla Costa R, Cossich ES, Tavares CRG. Influence of the temperature, volume and type of solution in the mercury vaporization of dental amalgam residue. Sci Total Environ. 2008;407(1):1-6.

Type of Study: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Water quality and wastewater treatment and reuse

Received: 2025/08/11 | Accepted: 2025/10/20 | Published: 2025/12/25

Received: 2025/08/11 | Accepted: 2025/10/20 | Published: 2025/12/25

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |